We Need an Ambassador to China, not to its Communist Party: In 1985, President Ronald Reagan appointed Winston Lord, a long-time China-hand and former director of policy planning at the State Department, to be the U.S. ambassador to China. Lord was an old, patrician, and somewhat arrogant foreign policy hand. For the previous eight years, he headed New York’s Council on Foreign Relations, an institution that prides itself on the conventional rather than creative.

Lord also had a chip on his shoulder. He considered himself the country’s top China hand, but National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger had cut Lord out of his China outreach during the Nixon administration’s secret diplomacy to Beijing. Kissinger liked to project an image of being the most brilliant man in the room. Too often, this was less because of his intelligence and more because he purged those who disagreed with him.

There was ample reason to challenge Kissinger and his notorious naiveté. Kissinger, for example, once described Chairman Mao Zedong and Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai as two of the three most impressive leaders he met. In reality, Mao and Zhou played Kissinger like a fiddle. In China, personalities trump systems. Chinese Communist Party officials approached Kissinger through that lens, the same way, using him to bypass American checks-and-balances.

Kissinger’s willingness to play into this system empowered the Chinese Communist Party by giving them a monopoly over engagement. This was why, years later, the Communist leadership grew so upset when Ambassador Lord decided to speak directly to students during a visit to Beijing University, and both complained and sought to freeze the ambassador out. Lord was not imparting revolutionary sentiment at the time.

Rather, the Chinese Communist Party meant its over-the-top reaction to prevent any future attempts to bypass it in order to protect its monopoly. Secretary of State George Shultz did not stand up for Lord, effectively causing him to lose face in Beijing. Perhaps had Shulz done so, the Tiananmen Square protests would not have caught the U.S. establishment so off-guard the following year.

Today, the same dynamics are at play.

R. Nicholas Burns, a former State Department spokesman and long-serving diplomat and lobbyist, is U.S. Ambassador to China. Burns is the personification of convention. Throughout his diplomatic career, he has prioritized his diplomatic outreach to cultivate power rather than principle. For President Joe Biden and his team, he was a safe choice. Climate envoy John Kerry knew Burns well and did not need to worry about him rocking the boat on Uyghur human rights when Kerry wanted to focus on climate negotiations.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken was happy to have Burns in Beijing to keep the ambitious diplomat from seeking his job (one Burns doing that is enough) and, arguably, from antagonizing once and future business partners.

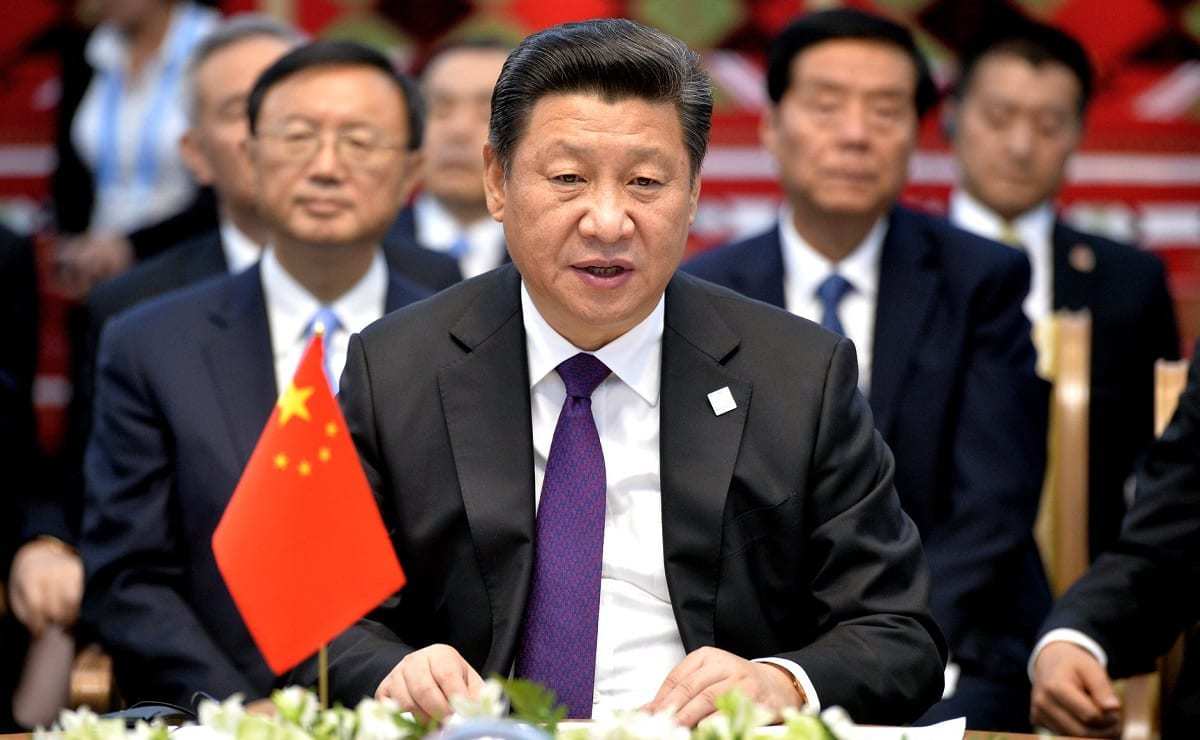

With dissent in China reaching the boiling point amidst President Xi Jinping’s repression, corruption and draconian COVID lockdowns, the United States needs an ambassador like Winston Lord accidentally was. The U.S. ambassador should be a man who is willing to break the artificial conventions the Chinese Communist Party seeks to impose in order to speak to all Chinese, even those whose Communist Party social credit scores may be low.

Burns should leave the embassy compound and visit Beijing University, other campuses, and those who escape from lockdown centers and prison camps. He should do so without the permission of Chinese Foreign Ministry minders. The Senate confirmed Burns to be ambassador to China, not to the Chinese Communist Party. Now more than ever, Washington needs someone who can reach beyond the ruling cabal.

If Burns is not up to the task, he should come home.