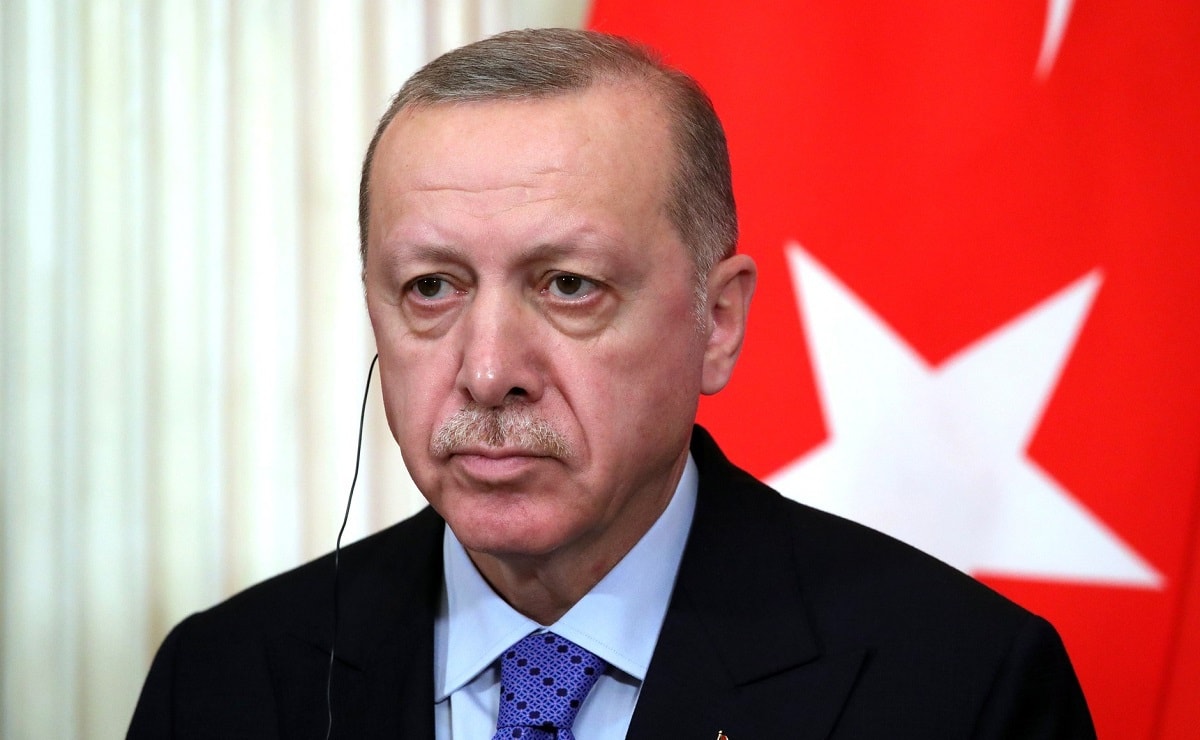

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, eager to cement a third decade in power, appears ready to set May 14, 2023, as the date for Turkey (Türkiye)’s next presidential elections.

Many Turkey-watchers, both in the United States and Europe, delude themselves into believing that Erdogan will ever step down peacefully.

He is a cynic when it comes to democracy: “Democracy is like a streetcar,” he famously quipped. “Ride it as far as you need and then step off.”

For Erdogan, elections are useful but not indispensable theater. He and his supporters like to brag that he has a popular mandate, but that does not mean he would gamble his future ambitions on free and fair elections.

Campaign Strategies

Erdogan has four possible strategies to survive in power as elections approach. The first is to win elections outright, but this could be difficult given Turkey’s tanking economy. The second would be to cheat. Erdogan controls the bureaucracy and media, would likely reject any meaningful election monitoring, and can simply declare that 2 + 2 = 5. Because Erdogan would consider the objection by any official to such math as akin to a confession of complicity in either the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) or the “Fethullahist Terrorist Organization” (FETO), he can count on silence. The third would be to declare a state of emergency and postpone or cancel elections.

Because Erdogan controls the judiciary, the constitution would be no impediment. The most likely course of action to justify such a move would be a military conflict. Perhaps Turkey will stage another false flag terrorist attack and blame Syria’s Kurds. Or perhaps Turkish forces will seize an unpopulated or lightly populated Greek island and dare Greece to react.

Even if Erdogan does not delay elections under such circumstances, he can use the crisis and whipped-up nationalist fervor to accuse any competing candidate of disloyalty, should they criticize him against the backdrop of war. These two strategies—fraud and false flags—need not be mutually exclusive. Nor need they be separate from a fourth strategy: the arrest of rivals.

A History of Using Such Strategies

This strategy Erdogan has already begun. After Erdogan failed to win meaningful Kurdish support in previous elections, in 2016, he ordered the arrest of Selahattin Demirtas, co-leader of the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP). Demirtas was young, charismatic, and well-spoken. Many Turks and Kurds nicknamed him the “Kurdish Obama.” His success in guiding the HDP past the ten percent threshold necessary to take seats in parliament helped deny Erdogan’s party the outright majority in parliament Erdogan’s ego and ambitions demanded.

When Turkey’s security forces came for Demirtas, the street was largely quiet. Only a few hundred Kurds protested. Some perhaps expected his imprisonment to be temporary, or hoped that diplomatic pressure from outside would compel his release. Erdogan, however, simply ignored the subsequent European Court of Human Rights finding that his Demirtas’ imprisonment was illegal.

The cynicism, pettiness, and small-mindedness of Turkish political culture played into Erdogan’s hands. Compounding all of this was anti-Kurdish racism. Other party leaders considered Demirtas’ magnetism a threat. He was the first Kurdish leader who even attracted support among Istanbul and Ankara’s liberal elite. Both center-left Republican People’s Party (CHP) leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu and especially right-wing Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) Devlet Bahceli, lack charisma. Despite repeated underperformance, both refuse to step down and continue to rule their parties as mini-dictatorships.

Prevailing Parties Benefit from Erdogan’s Play

Both Kilicdaroglu and Bahceli calculated that Demirtas’ downfall could be their gain. They also hesitated to stand up for a political leader who openly celebrated Kurdish culture. Neither called on their supporters to stand up for democracy, law, or principle. This was a miscalculation. Their silence led Erdogan to realize he could imprison rivals one by one.

And so the gradual purge has begun. Last month, an Istanbul court sentenced Istanbul Mayor Ekrem Imamoglu, a potential presidential candidate and a man who twice defeated Erdogan’s handpicked candidates, to more than two years in prison for allegedly insulting public officials with criticism of Erdogan’s policies and record.

Erdogan’s supporters now increasingly demand a similar fate for Kilicdaroglu. Former Erdogan cabinet ministers Ali Babacan and Ahmet Davutoglu split from the ruling party to form their own political parties. Both are also likely on Erdogan’s political hit list. Babacan, the weaker of the two, has already come under withering criticism in the state media for opposing Erdogan’s foreign policy and economic stewardship.

Davutoglu is a dead man walking. As foreign minister, he was quite openly an admirer if not an acolyte of theologian Fethullah Gülen. While Erdogan likewise was once tight with Gülen—a taboo subject in Turkey—he now alleges the exiled theologian to be a terrorist. The charge is false, but this is irrelevant for Erdogan, for whom guilt by association remains a potent tool.

As elections approach, the arrest of rivals could guarantee Erdogan a victory. The only real question is the order in which Erdogan will order their arrest.

Erdogan can then claim democratic legitimacy, but an election in such circumstances would be farcical. While leaders in Russia, Qatar, and Azerbaijan may praise his new term, his international legitimacy will be in tatters. In the long term, Erdogan seals his own fate. As in Apartheid-era South Africa, prison has become a badge of honor from which Turkey’s new generation of leaders will rise.

Dr. Michael Rubin, a former Pentagon official, is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and a senior lecturer at the Naval Postgraduate School.