Editor’s Note: Below is the final installment in a multi-part series on the new B-21 Raider stealth bomber by expert Philip Handleman. You can read all parts of the series here.

At the Air, Space & Cyber Conference in 2016, Secretary of the Air Force Deborah Lee James announced a break from the sequential bomber designation protocol. According to that protocol, the Air Force’s next bomber would have been designated the B-3. The chosen designation of B-21 would instead evince the aircraft’s coming of age in the 21st century.

In addition, Secretary James revealed the B-21’s official nickname, Raider, which immediately gave the bomber an illustrious cache. Selected from among more than 2,100 entries in a naming contest, Raider was derived from the daring Doolittle Raid of April 1942, in which 80 volunteers — the Raiders — launched from the pitching deck of the USS Hornet to avenge the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor a little more than four months earlier.

Led by the indomitable James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle, the crews bombed targets in and around Tokyo, flying 16 North American Aviation B-25B Mitchell medium bombers. The last surviving Doolittle Raider, Lt. Col. Richard E. “Dick” Cole, who had served as Doolittle’s copilot during the mission, was on stage at the naming ceremony.

In considering the 1942 mission’s connections to the B-21 Raider, it is worth noting that the B-25’s lineage offers a link of its own. In the mid-1930s, North American Aviation developed its first multi-engine bomber, a chunky high-altitude aircraft outfitted with two 1,200-horsepower turbo-supercharged Pratt & Whitney Twin Hornet engines and crewed by six airmen. The company assigned the bomber model number NA-21. When the Army Air Corps took delivery of the one flying article later in the 1930s, it was designated XB-21 — the first bomber to have the B-21 designation.

The XB-21, nicknamed Dragon, was a promising design. When flown, it outperformed the competing design from Douglas Aircraft. However, the Douglas bomber, the B-18A Bolo, was less costly, and the Army bought it instead.

The Bolo was based on Douglas’ DC-2 airliner, a stepping stone to the company’s breakout product, the popular and lucrative DC-3. Douglas pursued improvements to the Bolo, which culminated in a new configuration that included a sleeker fuselage and the DC-3’s stronger wings. The new bomber was designated B-23 and usurped the Dragon nickname. The XB-21 never went into production.

North American Aviation learned from its initial foray into multiengine bombers and followed up with a new design, the NA-40, that incorporated lessons from the XB-21. In turn, the NA-40 proved to be a bridge to the NA-62, which became the B-25 – meaning that the first B-21 evolved into the bomber flown by the Doolittle Raiders.

The B-25 was a mid-wing configuration with tricycle landing gear and dual fins, powered by two 1,700-horsepower supercharged Wright Cyclones. Like new designs from Martin and Douglas, the B-25 represented a next step into the future, if not exactly a radical leap. The B-25 was nicknamed the Mitchell to honor outspoken air power advocate William L. “Billy” Mitchell. A total of 9,816 B-25s were built, with various models operated in all combat theaters of World War II.

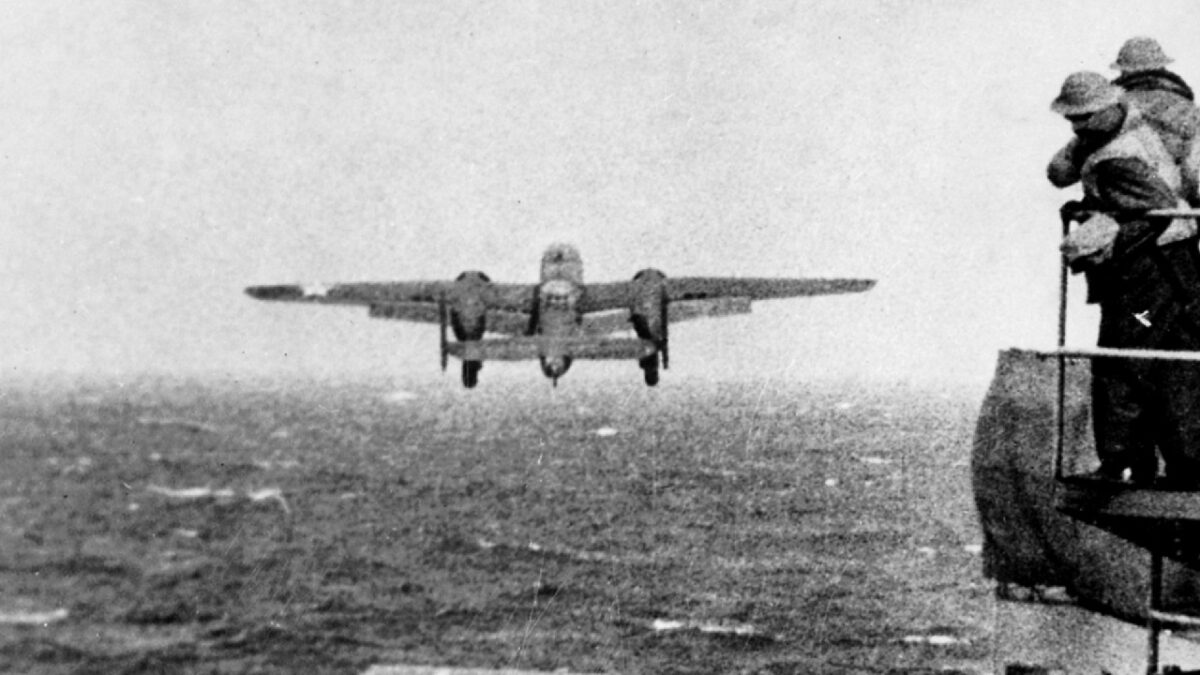

A U.S. Army Air Forces North American B-25B Mitchell bomber takes off from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8) during the “Doolittle Raid”. Original description: “Take off from the deck of the USS HORNET of an Army B-25 on its way to take part in first U.S. air raid on Japan. Doolittle Raid, April 1942.” Clarence M. “Bob” Logsdon(shorter man in foreground) and Allen Q. Nations (directly behind Logsdon) watch as a B-25 leaves the deck of Hornet on 18 April, 1942. Mr. Nations perished at the battle of Santa Cruz Islands when a Japanese “Val” dive bomber crashed into the Hornet’s signal bridge. Logsdon survived and in 2001 related “the death of the Hornet” in Robert Ballard’s (who found the Titanic) book, “Graveyards of the Pacific.”

Despite its modern features the B-25 was not designed to operate from Navy ships. Yet even when loaded with 2,000 pounds of bombs and extra fuel, the planes could be adapted to takeoff from the limited confines of a carrier deck. The Doolittle Raid was an ingenious slap-dashing of disparate assets to achieve an elusive military objective under the most intense pressures. Tellingly, the operational centerpiece — launching land-based bombers from an aircraft carrier — was never repeated. In this singular case, crews were saddled with the added disadvantage of having to launch approximately 200 miles before their intended launch-point because while en route, their carrier battle group had been sighted by Japanese picket ships. This meant they would not reach the landing fields in China awaiting their arrival at the conclusion of their mission’s long journey.

Doolittle and his crews used their fuel reserves for as long as they lasted. Most then either bailed out or ditched at sea. They knew at the outset that this was a possible ending, and yet they launched anyway. Such bravery earned the crewmen a lasting place in the pantheon of heroes.

When Doolittle returned stateside, he was promoted from lieutenant colonel to brigadier general and summoned to the White House to receive the Medal of Honor. His fellow volunteers were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. In the years that followed, the Doolittle Raiders received many additional honors, including the Congressional Gold Medal.

The raid on Tokyo and environs caused only minor damage, but the psychological impact was meaningful. After a steady stream of depressing news from the war zones, Americans finally got a morale boost. In contrast, the Japanese suddenly woke to the reality that their island nation was not untouchable after all. The B-25s flown by the Doolittle Raiders had made a difference in the face of extraordinary obstacles.

The B-21 Raider was unveiled to the public at a ceremony December 2, 2022 in

Palmdale, Calif. Designed to operate in tomorrow’s high-end threat environment, the B-21 will play a critical role in ensuring America’s enduring airpower capability. (U.S. Air Force photo)

While B-25s scored many successes across battlefronts from Europe to the Pacific, the bomber’s role in the Doolittle Raid stands out. Not surprisingly, a B-25 search on the website of the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force brings up the bomber in the Museum’s Doolittle Raid exhibit. That aircraft, an RB-25D, was plucked from the desert boneyard and reworked into a B-25B in the 1950s by volunteers at North American Aviation to match the lead bomber that was flown by Jimmy Doolittle and Dick Cole.

Most of the raid’s participants survived the mission and continued to serve. In subsequent years reunions took place on the Raid’s anniversary. At the reunions, the remaining Doolittle Raiders developed the tradition of drinking a toast to their fallen mates, using silver goblets engraved with the Raiders’ names.

At the end of the toast, the goblets of those who had died in the course of the year were turned down. Placed in their portable wood and glass display case, which had been built by Cole, the goblets would remain undisturbed until the next reunion. Now exhibited in that display case near the uniquely restored B-25 at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, all 80 goblets are facing down, never to be used again but serving as symbols of the eternal bond among heroic men of the air.

It is fitting, and some would say overdue, that 74 years after brilliantly executing a near-impossible mission, the crews of the Doolittle Raid received another accolade: a bomber named to honor their courage and commitment to duty.

In the years to come, the measure of the B-21 Raider will hinge on many factors, but probably none as much as its greatest asset — the men and women at the controls, either on board or remotely, who will be charged with upholding the proud heritage of their bomber’s namesake. As in many armed conflicts of the past, including the one in which the Doolittle Raiders demonstrated awesome grit, future fights are likely to be tests of will. Their outcome depends not just on the caliber and plentitude of the weapons employed, but on the strength of character and keenness of warrior spirit of those wielding them.

Philip Handleman is a pilot and aviation author/photographer. With retired Air Force Lt. Col. Harry T. Stewart, Jr., he cowrote Soaring to Glory: A Tuskegee Airman’s Firsthand Account of World War II. Mr. Handleman’s photograph of the Air Force Thunderbirds was featured on the postage stamp honoring the 50th anniversary of the Department of the Air Force in 1997.