Editor’s Note: This is part III of a multipart series looking at the origins and potential of the B-21 Raider. You can find part I here, part II here, part IV here and part V here.

What Makes the B-21 a Gamechanger

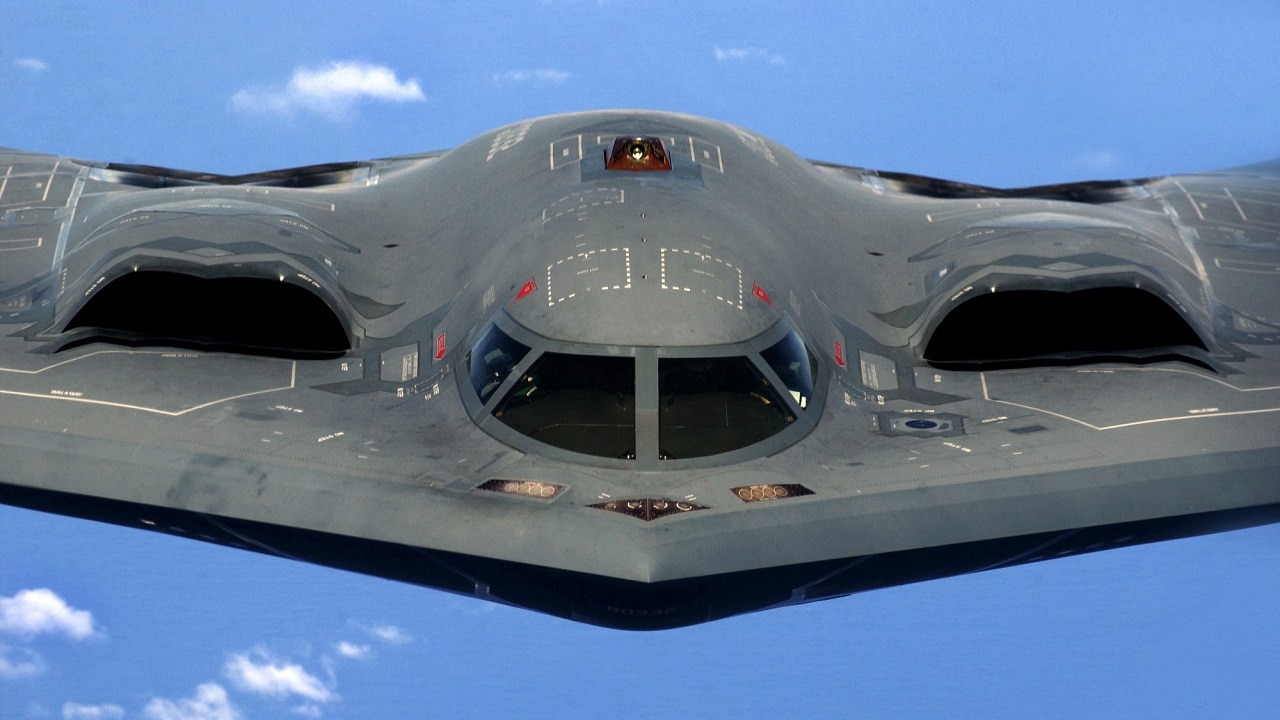

The things that look to be gamechangers in setting the B-21 apart are the secrets hidden within its inner sanctum. At the bomber’s December 2, 2022 rollout, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin said as much: “You know, the B-21 looks imposing. But what’s under the frame and space-age coatings is even more impressive.”

The powers stemming from the B-21’s core – less the touchable gadgets and more the abstract capacities – involve the moving and digesting of raw data faster than humans can think. The B-21’s networking prowess is intimated to include the ability to securely share a wealth of gathered inputs via the electromagnetic spectrum while the bomber acts contemporaneously as a bomb delivery platform, communications relay node and command-and-control manager.

The B-21’s advances stand to transform the nature of air warfare and could alter perceptions of the bomber from a mere bomb-dropper to a multifaceted atmospheric battle-star that leapfrogs the enemy’s decision-making through lightning-quick processing and sharing of the information flow, giving new meaning to the old adage that knowledge is power.

Among its “under the frame” breakthroughs, the B-21 is expected to have an optionally-crewed capability as that was an element of the contract. While missions into the foreseeable future will likely be flown with crews on board, having the option to operate a large stealthy bomber interchangeably with or without onboard pilots would chart new ground. In either case, B-21 combat sorties are contemplated, at least in part, as formation flights with smaller un-crewed combat air vehicles now in development.

Known as Autonomous Collaborative Platforms or ACPs, these ultra-sophisticated drones will constitute part of a family of systems to be built around the B-21 – the concept where the bomber is not just an airplane but a system of systems. That concept is to have equal applicability to the F-22 Raptor’s forthcoming replacement, the NGAD (Next Generation Air Dominance) fighter, which is on track to be the Air Force’s first sixth-generation fighter with initial operational capability possibly by 2030.

ACPs can be thought of as “loyal wingmen,” but will provide much more than such traditional escort attributes as situational awareness cues and protection against interceptors. In fact, ACPs are likely to be reconfigurable for multiple purposes.

Conceivably launched by the bomber itself or supporting aircraft, the diversity of roles served by these un-crewed vehicles will, according to the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, probably include offensive/defensive counterair, suppression of enemy air defenses on the ground, intelligence-surveillance-reconnaissance, communications relay and jamming. Some of these roles would be additive. For example, carefully positioned ACPs would extend the bomber’s already far-reaching communications linkages.

ACPs may even join the bombers in attacking the targets. They could function in massive swarms or serve as decoys. And, unlike old-style crewed escort aircraft, these drones would be expendable.

The multidimensional chessboard involving coordination between crewed and un-crewed vehicles will have too many pieces moving too fast for humans alone to manipulate. Achieving dominance of the electromagnetic environment while concurrently executing either a kinetic or directed-energy attack on assorted ground targets, some of which may be in motion, will necessitate rapidly fusing and sifting through throngs of data by nimble computers, adjusting frequency settings, trajectories, pitch angles and more in an immensely fluid threat ecosphere. Reliance on advances in automation, artificial intelligence, predictive analytics and machine learning is the only way the new bomber is going to be able to make the complexity manageable.

In fact, Northrop Grumman used the occasion of the rollout to talk up the bomber’s new software and cloud computing tied to a “digital twin.” The point was to focus attention on the significant level of digitization as an enabler of a production-ready bomber right off the bat, long-term maintenance sustainability and an open architecture for ease of future upgrades.

As laudatory as these capabilities will be, one senses that they represent the tip of the proverbial iceberg in terms of the full scope of the new bomber’s processing power and networking capacity. In its advanced computing systems, the B-21 may well cross a new technological threshold.

Northrop Grumman comes to the table with an extensive background in software development, having taken the technology both figuratively and literally to new heights. It pioneered autonomous operations with its cutting-edge high-altitude RQ-4 Global Hawk/MQ-4C Triton family of drones. An outgrowth of that program is what the company calls a “leading prototype” of the Defense Department’s Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) system, a generic warfighting tool prioritized by the Pentagon. According to the implementation plan for the system, released publicly on March 17, 2022 by Deputy Defense Secretary Kathleen Hicks, JADC2 is meant to ensure that warfighters “keep pace with the volume and complexity of data in modern warfare.”

Northrop Grumman’s JADC2 version, known proprietarily as the Distributed Autonomy/Responsive Control (DA/RC) system, is described on the company’s Web site as a “transformational software technology” that “connects and controls a wide range of complex systems across all domains and services in highly contested environments.” The company indicates that DA/RC will enable human-machine collaboration for enhanced warfighter decision-making in the world’s increasingly lethal, maze-like battlespaces.

While the company does not expressly say that DA/RC or a derivative will be the basis for the B-21’s connectivity and control functions, the system as presented possesses must-have attributes for the new bomber. Also, Air & Space Forces Magazine reporting indicates Northrop Grumman has a stealthy Global Hawk replacement, the RQ-180, in the works and that it bears a resemblance to the B-21. This suggests that some version of the company’s advanced software package from its high-flying drones will be central to the B-21.

Here, though, is arguably one of the B-21’s potential pitfalls for, as real-world experience has demonstrated, systems heavily laden with software are invariably subject to a mix of internal and external vulnerabilities. Any software-centric machine is only as good as the programmers’ vision. That means having to think through every possible scenario and devise corresponding lines of code so that hiccups do not happen at the most trying of times.

Engineer and former Air Force pilot James Albright asserted in a three-part series on aircraft reliability for Business & Commercial Aviation in early 2023 that aircraft software can never be fully tested except in the real world “because the real world is too complicated to predict in a research and development environment.” He posited that finding where design theory falls short of operational reality takes longer where software is involved, prolongating aviation’s customary discovery-and-repair cycle.

While cockpit automation has long been a staple of everyday flight as seen through the widespread use of such workload-relieving systems as autopilots and auto-throttles, the trend in highly advanced aircraft is for the computer operating system to serve as the platform’s wired nerve center – if not the brain then an indispensable lobe. Unless the baseline software and what are likely to be its many updates over time are as near to flawless and impregnable as humans can make them, the B-21’s software dependency could become its Achille’s heel. Yes, ironically, one of the very things that makes a combat aircraft like the B-21 so formidable contains the seed to render it vulnerable.

Northrop Grumman

While some point to statistics that purport to show aircraft have become safer with the introduction of software into flight operations, the track record of software in airplanes is a cautionary tale. The successful integration of the former into the latter hinges on effectively managing the inescapable tension between aviation’s traditionalist wrench-turners and their latter-day colleagues in the design-build enterprise, the computer geeks. The two represent distinct cultures that are not often in tune. Unfortunately, software flaws in some of the most high-tech planes have caused troublesome effects in the air and on the tarmac.

The most often cited example is when a formation of six F-22s crossed the International Date Line for the first time during a 2007 flight from Hawaii to Japan. The onboard computers were said to have suffered a systemwide “crash,” leaving the brand-new fighters bereft of their navigation systems, radios and certain other instruments. It could have been a calamitous event had it not been for clear weather and accompanying tanker aircraft that provided visual guidance back to the departure point. While the Air Force never publicly explained the cause, it is presumed that the fighters’ software was inadequately programmed for the initial passage through the imaginary line that represents the divide of calendar days between East and West. A fix was reportedly instituted within the next 48 hours.

The even newer F-35 Lightning II has had its own tortured history of software difficulties, causing aircraft availability to suffer. The Director of the Pentagon’s Office of Operational Test and Evaluation, Nickolas Guertin, had particularly harsh words for the F-35’s software in his 2022 annual report, issued in January 2023. Referring to the fighter’s software modernization effort, the report stated: “The F-35 program continues to field immature, deficient, and insufficiently tested Block 4 mission systems software to fielded units. The operational test (OT) teams continue to identify deficiencies that require software corrections and, with them, additional time and resources.” The report also criticized the F-35 Joint Program Office for not adequately planning for operational tests of the new hardware configuration known as Technology Refresh 3 (TR-3).

Additionally, the fighter’s computer-based maintenance system, Autonomic Logistics Information System (ALIS), has been notoriously problematic, also resulting in unacceptable mission capability rates. The system is being replaced by means of a transition to a new system, Operational Data Integrated Network (ODIN), with the associated hardware of ODIN Base Kits (OBKs) already having been distributed to selected field units to take the place of ALIS Standard Operating Units (SOUs). The report describes the three-step process for the transition as behind schedule due to delays caused by the reallocation of resources to correct issues with the first step’s software release. According to the report, the originally planned flight testing of the ALIS “containerization” has been moved back nearly a year, from July 2023 to June 2024.

The search for light at the end of the F-35’s software tunnel has been going on a long time. Production of the fighter began in 2006 and as of February 1, 2023 Lockheed Martin’s Web site indicates 890 F-35s have already been delivered.

In theory, software should enhance a complicated machine’s functionality and ease of operation. For executing exceptionally complex tasks, software plays an absolutely essential role by processing data at speeds that would not otherwise be possible. However, as noted, software anomalies have had a nasty habit of sprouting up unexpectedly, jeopardizing not only readiness but also safety. Those in the field are left to grapple with glitches that cause systems not to work as advertised, forcing them to perform nagging reboots or having to simply wait for software updates that may contain glitches of their own. Cost and efficiency have suffered too, frustrating bureaucrats seeking to manage tight budgets.

Innocent oversights by software programmers are one thing. Add to that the malicious activities of enemy hackers who will spend every waking hour seeking to exploit weak spots with relentless cyberattacks. How much resiliency will be built into the B-21’s connectivity and control software? If one bomber’s system is taken down would it trigger a domino effect? What are crews to do if they lose contact with their command authority?

Several months before the B-21’s rollout, on August 23, 2022, the Air Force addressed the question of severed communications links between crews and their higher-ups during combat operations. In Air Force Doctrine Note 1-21, which introduces a new “scheme of maneuver” known as Agile Combat Employment (ACE), the service concedes that it should be “expected and anticipated” that in modern war some “force elements” will be cut off from “higher echelon commands.” The document instructs that in such instances the crews should focus on carrying out the commander’s intent and exercise initiative to seize “emergent opportunities.” That is fine as far as it goes, but there appears to be no Plan B if enemy hackers go beyond disrupting communications and infiltrate the B-21’s computers.

B-21: Software Is Key

The pressure is on Northrop Grumman’s software developers to come up with an ironclad protective bubble against hacking attempts as well as inadvertent bugs. Managing to do so would be a stroke of genius on par with Jack Northrop’s flying-wing epiphany. The next major milestone is coming as the company preps the newly-introduced bomber for its flight test program, expected to commence at Edwards Air Force Base in mid-2023.

B-21 Raider

If the company can smoothly integrate its software into its exquisitely tweaked airframe, fashioning an airtight seal against the would-be interlopers and snuffing out the gremlins a priori, the plane will be on course to betoken a new era of aerial weaponry and open a significant new chapter in the history of air warfare. Through mastery of the complex technologies going into its flagship platform, Northrop Grumman has a real shot at justifying its claim that the B-21 is the world’s maiden sixth-generation aircraft.

Author Expertise and Experience

Philip Handleman is a pilot and aviation author/photographer. With retired Air Force Lt. Col. Harry T. Stewart, Jr., he cowrote Soaring to Glory: A Tuskegee Airman’s Firsthand Account of World War II. Mr. Handleman’s photograph of the Air Force Thunderbirds was featured on the postage stamp honoring the 50th anniversary of the Department of the Air Force in 1997.