Too often, military equipment platforms are seen in overly simplistic terms. They might be viewed unfavorably as little more than a boon for contractors, or as a scapegoat that must be killed in the name of better, faster, and cheaper technology. However, this same equipment is the backbone of our military’s capability. It gives us the capacity to deter our adversaries and wage war if necessary. A man without a machine in the U.S. military is limited in training and skill, and eventually there is a cost to our global presence.

- Image Credit: AEI.

When the capital assets that power our armed forces age out and retire, and recapitalization and replacements stall, capability gaps grow. This leads to worsening manpower shortages and eventually retention challenges, not to mention failures of deterrence.

Nowhere is this issue more acute than in the U.S. Air Force. The aging out of equipment without ready replacements is worsening the Air Force’s pilot shortage, which was dubbed a crisis just a few years ago. The trainer jets used to qualify new pilots are so decrepit that the timeline it takes to create a pilot has elongated from 24 months to nearly four years.

After being commissioned as an officer in the Air Force, a future pilot now typically waits for two years just to begin pilot training. Another two years are needed on average to create a highly skilled pilot, depending on the type of aircraft. These lengthy delays, and the uncertainty that comes with them, are causing the Air Force to shed pilots. If a young person joined the Air Force to fly planes, and there are not even enough planes to train on, they will leave and fly instead for private airlines. That is exactly what 3,280 of them did just last year.

So is it the chicken or the egg? Not enough pilots or not enough aircraft? In this case, it seems the lack of aircraft is contributing to and compounding the existing problem of not enough pilots.

The problem goes beyond a dearth of aircraft and pilots. The Air Force’s national air-crew crisis has been brewing for years, as the Force has been short thousands of maintainers for the past decade. Every missing maintainer creates more strain for the ones that remain, which creates a compounding negative effect on force retention.

As the services struggle to bring in fresh talent, those who are already in uniform are assigned the extra tasks that the new recruits would have picked up. The result is undermanned units that are overworked. Eventually, the overburdened troops decide they cannot do more with less and bolt for the exits.

As the pilot corps shrinks and the number of flyable planes drops, flying hours similarly have fallen. The last two decades have seen a steady decline of over 1 million funded flying hours per year in the Air Force, “offering pilots fewer opportunities to contribute and keep their skills current.”

Antique aircraft are less reliable and take longer to repair. Planes in the shop mean there is no iron on the ramp.

Fewer flying hours also make airmen less safe and more prone to costly accidents. Further, maintainers and pilots who are idle for a period of time can lose their qualifications and have to start over once planes become available.

If you’re keeping count, that’s three different crises affecting manpower, machinery, and maintenance — each exacerbating the effects of the others. These crises didn’t crop up overnight. In the words of one former fighter pilot, the past is prologue.

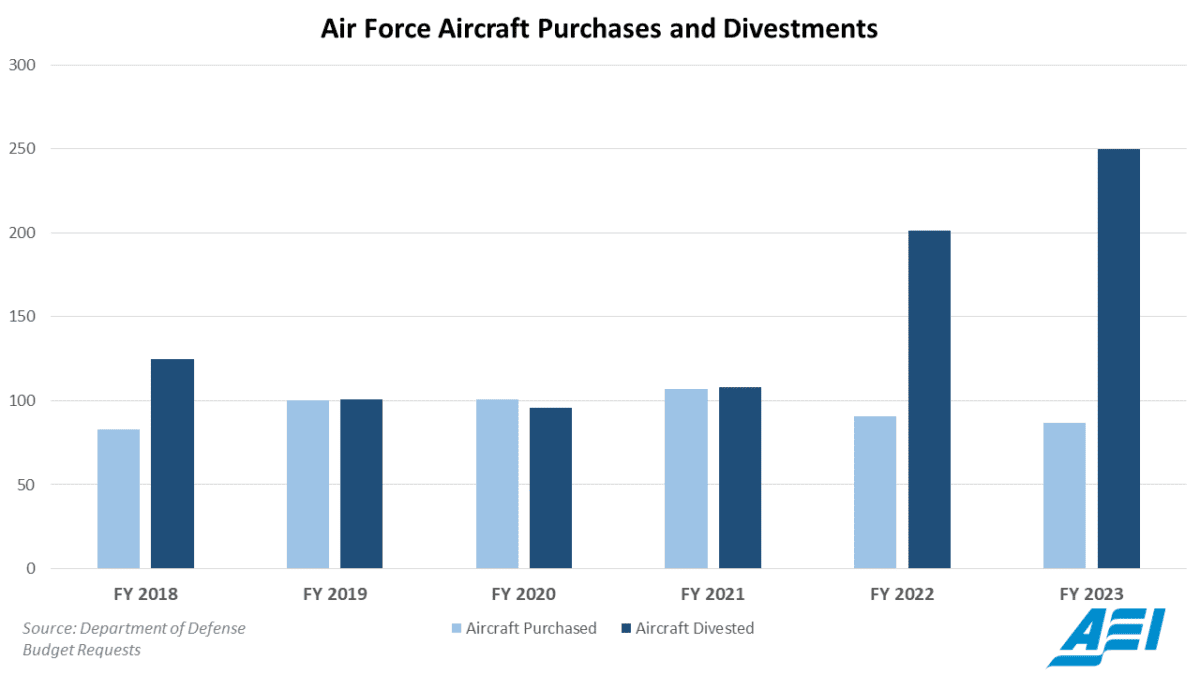

“In the 1990s, [the US Air Force] divested too many aircraft, they closed down too many pilot training bases. They simply don’t have the capacity to produce the number of pilots that they need, and they don’t have the aircraft required to absorb the pilots they do create,” according to Heather Penney at the Air Force Association.

Despite what leaders say, the Air Force needs airplanes. In this year’s budget request, President Joe Biden requested just 72 fighter aircraft — while divesting 89 — and zero new trainer aircraft. This only exacerbates the airframe shortage, which worsens the pilot and maintainer deficiencies and cuts down on global engagements.

The Air Force’s former fighter presence in Japan shows this doom loop at work. Seven months have passed since the Air Force decided to withdraw its once permanently-stationed F-15C/D fighters from Kadena Air Force Base in Okinawa. The Air Force still lacks a firm plan for what comes next, likely because they don’t have enough airplanes to go around to meet the demands of global presence and deterrence.

As the prime minister of Latvia told Politico this week, “deterrence has to be credible. And credible means actual forces, actual capabilities.” Getting smaller should not be the preferred way to pay for future technologies when bolstering global deterrence is the urgent work of now.

About the Expert Author of This Content

Now a 1945 Contributing Editor, Mackenzie Eaglen is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), where she works on defense strategy, defense budgets, and military readiness. She is also a regular guest lecturer at universities, a member of the board of advisers of the Alexander Hamilton Society, and a member of the steering committee of the Leadership Council for Women in National Security.