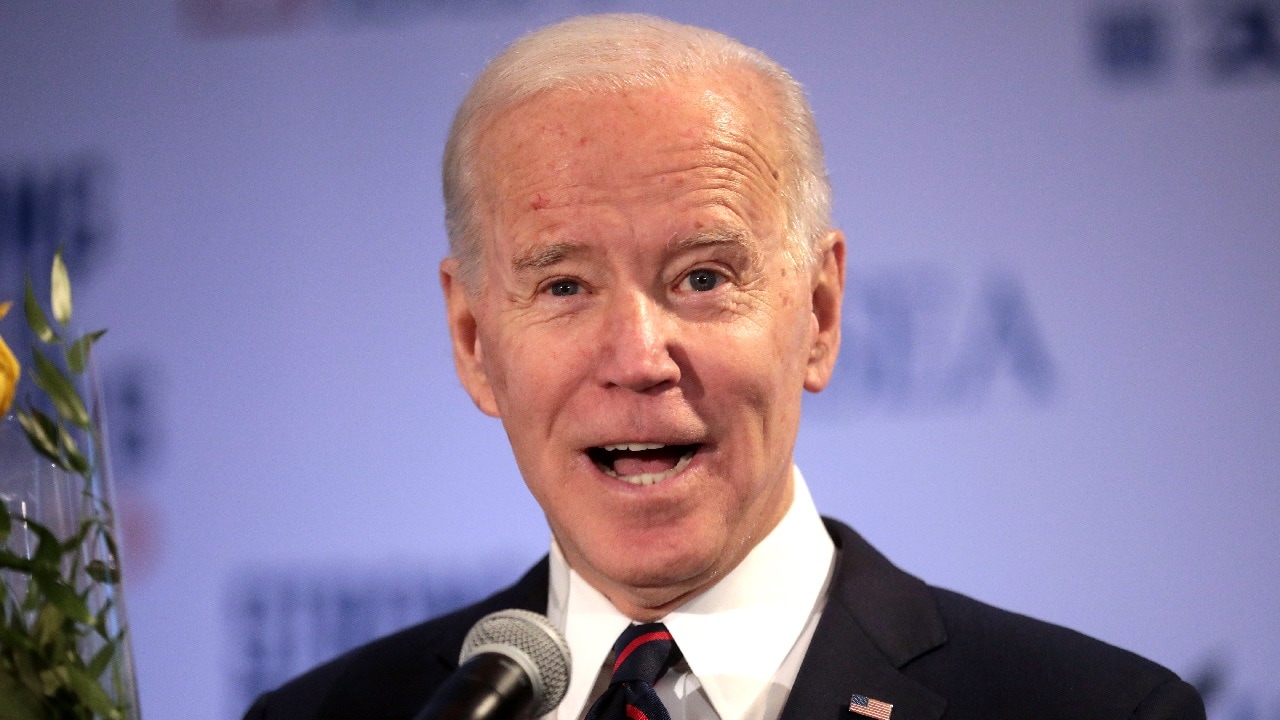

President Joe Biden was set to meet with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy last Friday after a previous meeting with the Republican official failed to secure an agreement to raise the debt ceiling. However, that meeting as put on hold to give each side’s staff more to time talk before another round of higher-level negotiations take place.

In last week’s negotiations, the president, McCarthy, and Democratic Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer discussed raising the debt ceiling to avoid defaulting on payments. House Republicans have so far refused to agree unless the maneuver is attached to strict spending reductions.

Democrats, however, want to see the debt ceiling raised without any framework for how spending should be managed.

Speaking to reporters in the Roosevelt Room, the president derided the “politics, posturing and gamesmanship” going on between the two parties, and said that the possibility of defaulting must be taken off the table entirely.

What Is A Debt Ceiling?

The federal debt ceiling is the amount of money that the federal government has the authority to borrow. The federal government typically borrows money to pay for a variety of social programs like Social Security, as well as paying federal employees’ salaries. Raising the debt ceiling would allow the government to borrow more when necessary, but to achieve it, Congress must first agree on a budget.

If Congress fails to agree on a budget and the debt ceiling is not raised, the United States will default on its debt payments. Failing to raise the debt ceiling also forces the federal government to shut down. Any activity that costs money ceases until the debt ceiling is finally raised.

Raising the debt ceiling is an increasingly common maneuver — it has happened 80 times since 1960. But the frequency with which this takes place worries politicians and financial experts. The United States has owed more than its gross domestic product for years.

The U.S. national debt exceeded GDP, the monetary measure of the value of all goods and services sold in the United States, in 2013. At that time, GDP and the national debt stood at around around $16.7 trillion. Today, the national debt is more than 120% of GDP, sitting at around $31.38 trillion.

Republicans argue that the national debt needs to be reduced and that constantly raising the debt ceiling without implementing strict spending regulations will make the problem worse. A group of 43 Senate Republicans vowed on Saturday to oppose raising the debt ceiling unless the president and House and Senate Democrats get behind “substantive spending and budget reforms.”

What Biden Says He Could Do

Biden has also put forward a radical proposal to raise the debt ceiling without the support of Congress.

On Tuesday, following a meeting with McCarthy and Schumer, the president said that he might use the 14th Amendment of the United States Constitution to raise the debt ceiling unilaterally.

“I have been considering the 14th Amendment,” the president said. “I’ll be very blunt with you, when we get by this, I’m thinking about taking a look at — months down the road — to see what the court would say about whether or not it does work.”

President Biden seems to believe that Section 4 of the 14th Amendment makes it unconstitutional for the United States to fail to make debt repayments. Presidents before Biden have refused to use this argument over concerns that it is not legally sound, but if Biden is right, a legal challenge to the debt limit could be forthcoming.

The 14th Amendment outlines how the “validity of the public debt, authorized by law…shall not be questioned.”

Can He Do It?

Even if the president can pull it off, invoking the 14th Amendment won’t immediately solve the debt ceiling problem.

The federal government may not be able to pay its bills unless the debt ceiling is raised by June 1, 2023. That gives the president less than a month to come to an agreement with Republicans or to successfully challenge the legality of the United States failing to pay its debts.

“The problem is it would have to be litigated,” the president himself admitted to reporters on Tuesday. “And in the meantime, without an extension, it would still end up in the same place.”

Republicans don’t believe that the president’s assessment of the 14th Amendment, and the legality of failing to pay debt, is accurate.

Speaking after his meeting with the president, McCarthy said the president was failing to reach across the aisle.

“Really think about this. If you’re the leader, if you’re the only president and you’re going to go to the 14th Amendment to look at something like that…I would think you’re kind of a failure of working with people across sides of the aisle, or working with your own party to get something done,” McCarthy told reporters at the Capitol last week.

Speaking to Fox News last week, experts expressed concern about Biden’s plans and cast doubt on their viability.

Constitutional-law professor Thomas Lee told the outlet the plans may not be completely sound.

“I wouldn’t call it crazy, because you know, it’s plausible based on a reading of the text,” Lee said. “But given the context, I just don’t think it’s the best reading of it.”

The Fordham University professor added that the president does not have the authority to borrow money to pay the debt, and that only Congress has the power to do such a thing, as outlined under Article 1, Section 9. Without the ability to borrow money, therefore, it is unclear how the president would pay the U.S. debt, even if his reading of the 14th Amendment is accurate.

Biden might go ahead with his legal challenge, but it presents a multitude of problems, and it does not address the core issue: that the two sides of the aisle simply cannot agree on how to handle the nation’s rapidly growing debt.

MORE: Kamala Harris Is a Disaster

MORE: Joe Biden – Headed For Impeachment?

Jack Buckby is 19FortyFive’s Breaking News Editor. He is a British author, counter-extremism researcher, and journalist based in New York. Reporting on the U.K., Europe, and the U.S., he works to analyze and understand left-wing and right-wing radicalization, and reports on Western governments’ approaches to the pressing issues of today. His books and research papers explore these themes and propose pragmatic solutions to our increasingly polarized society.