With nearly 40 percent of America’s attack submarines out of commission and new construction struggling to increase, it begs the question of whether and how Australia will receive this unprecedented capability and tech-sharing to deter Beijing anytime this decade.

The joint fleet that could result from AUKUS should be a force multiplier of protection for America and its allies. But absent enough dollars and manufacturing capacity, fast, the deal could wind up exacerbating our attack sub shortfall and therefore fall apart.

While the tri-party deal is timely, it must be executed smartly and with greater urgency. The risky zero-sum approach of having more submarines forward-based in the Indo-Pacific at the expense of our own sub fleet should be unacceptable. The world’s oceans are not getting any smaller.

Washington should instead seek to do both: grow allied submarine fleets and rebuild its own.

Australia Has a Problem: New Sub Construction Stuck in Neutral

The U.S. will sell between three and five attack submarines in the first pillar of the AUKUS agreement. In exchange, Australia will provide basing rights to U.S. submarines and invest in existing yards.

As the alliance takes shape, questions are being raised as to whether the U.S. military is capable of doing it all. Plagued by maintenance and construction delays, America’s submarine yards are underperforming relative to historic recapitalization rates. The Navy must increase the production of submarine tonnage by 5.5 times between fiscal years 2011 and 2025.

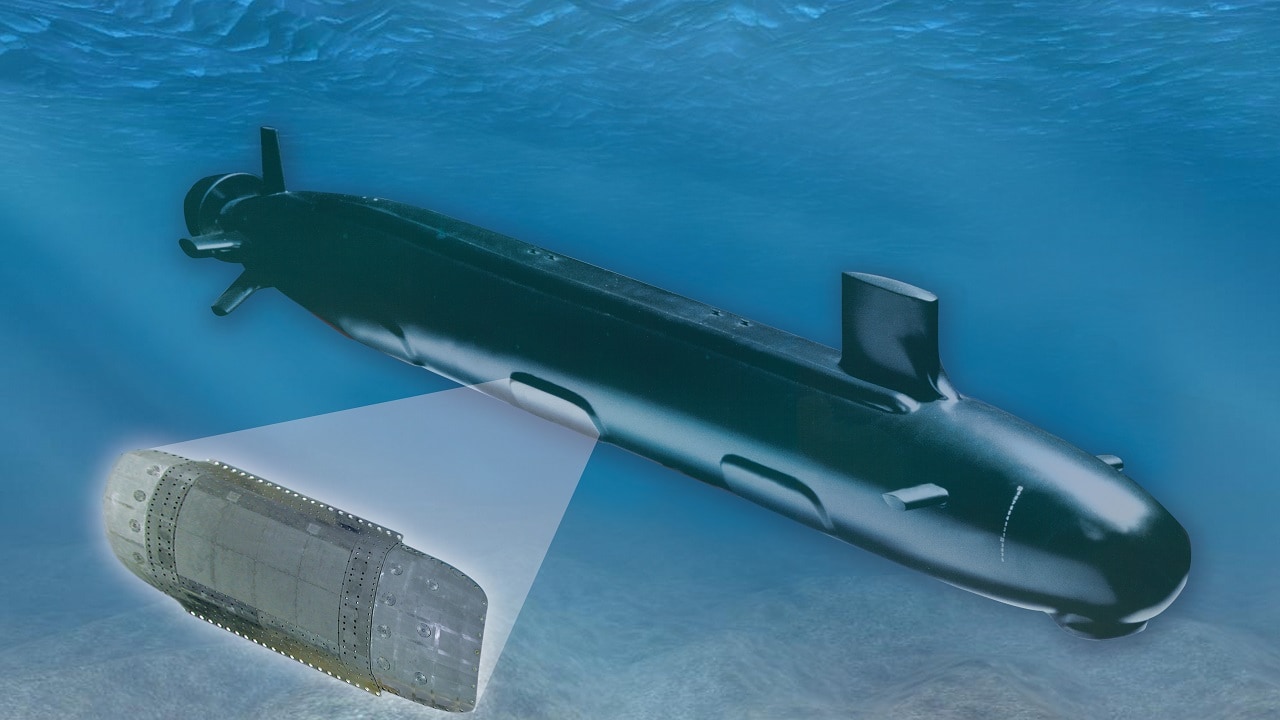

Attack submarines form the backbone of U.S. deterrence. While the Navy set a 30-year goal for a fleet with 66 nuclear-powered attack submarines, today we have just 49 (and dropping). Worse yet, only 31 of these are operationally ready as years of maintenance delays have culminated in a shipyard logjam that will take years to resolve.

Although Virginia-class SSNs are being consistently procured at a rate of 2 boats per year, the average actual production rate stands at just 1.2 subs per year—far below expected retirements. Alongside this, the Navy is buying next-generation Columbia-class ballistic missile subs, which have the tonnage of roughly two-and-a-half Virginias.

As the Navy’s top priority, the Columbia will continue drawing workforce and resources away from the Virginia in order to maintain a schedule. Therein lies the challenge: the new boomer has no margin for delays. This is adding risk to the recovery of Virginia-class production at a time when new attack construction needs to increase to a 2.33 build rate per year to account for AUKUS transfers.

Additional Funds for the Submarine Industrial Base Has Not Matched Tonnage

The submarine industrial base isn’t equipped to build the number of submarines the Navy needs. While COVID-19 has passed, a return to pre-pandemic production has yet to materialize. The pandemic accelerated a generational turnover in the shipyard and supplier workforce. Now the submarine industrial base must hire 100,000 skilled employees over the next decade; no small feat.

Numerous other problems plague our submarine maintenance, ranging from sole-source suppliers to aging capital equipment. Chronic underinvestment has led to shortages of spare parts, forcing crews to cannibalize parts from other depot-laden vessels, exacerbating delays. Worse yet, all of this work is bottlenecked in only a half dozen shipyards in the entire country that can perform depot-level maintenance on nuclear-powered vessels.

To simultaneously boost the size and readiness of the Navy’s SSN fleet and facilitate a submarine transfer to Australia, the Navy must double submarine production. This will demand additional funds in both the construction of attack subs and investment in the submarine workforce to buy long lead items early, train new workers more often, and possibly even open new yards needed for construction and maintenance.

While Pentagon leaders have hailed AUKUS as a “one in a generational opportunity,” there is no corresponding “generational” investment to see it through.

Earlier this year, the Biden administration requested $2.4 billion to increase construction capacity in the submarine industrial base over the next five years. Over that same period, the Navy is set to invest $44.7 billion in total submarine construction, including Columbia class. That $2.4 billion investment amounts to just a 5.3 percent increase over Navy plans.

While Australia should be lauded for its $3 billion investment in America’s submarine industrial base, the combined U.S.-Australia single-digit investments will not result in doubled productivity.

Congress is Sending Clear Signals to the Administration on Needed Next Steps

To satisfy commitments to AUKUS and bolster our position in the Indo-Pacific, Congress must work with the Navy to develop a concrete and well-funded plan to bolster the submarine industrial base.

The AUKUS alliance and transfer of attack submarines to Australia has the potential to be a tremendous force multiplier for allied combat power in the Indo-Pacific. Absent hefty resourcing, however, this deal could result in a net decline in credible combat power.

The Administration has a chance to make its most important foreign policy goal successful by requesting the authorities and appropriations necessary to resolve the risk within the submarine industrial base. To strengthen deterrence in Asia, Washington must increase submarine capacity to boost combined capacity rather than allow a zero-sum trade away.

The detailed implications of AUKUS along with a thorough industrial base modernization blueprint should be presented to Congress before it authorizes permanent submarine transfers. If the White House does not start this serious work now, the submarine transfer in 2024 is at risk.

Keeping AUKUS on track firstly requires a unified partnership of Congress, the Navy, and the White House.

About the Author

Now a 1945 Contributing Editor, Mackenzie Eaglen is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), where she works on defense strategy, defense budgets, and military readiness. She is also a regular guest lecturer at universities, a member of the board of advisers of the Alexander Hamilton Society, and a member of the steering committee of the Leadership Council for Women in National Security.