The West African nation of Liberia and the United States have always had a special relationship. Freed American slaves founded the country, one of Africa’s oldest independent states, and they named its capital Monrovia over the fifth American president James Monroe.

Over the decades, the United States and Liberia shared close military ties and, with the Firestone rubber concession, economic ties as well. After the Cold War, however, the United States grew complacent. Liberia also descended into civil war, first between 1989 and 1997, and then from 1999 until 2003. Successive U.S. administrations worked to help Liberians regroup and recover. In 2011, President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf and activist Leymah Gbowee both shared the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts in “peace-building” and “non-violent struggle.” In 2017, George Weah, a soccer star who had played for various African clubs as well as AC Milan, won the presidency and took office in January 2018. Liberians soon realized they made a grave mistake. Weah may have been a household name, but there was a reason why none of his teammates ever selected him to be captain: Simply put, he was never a leader of men.

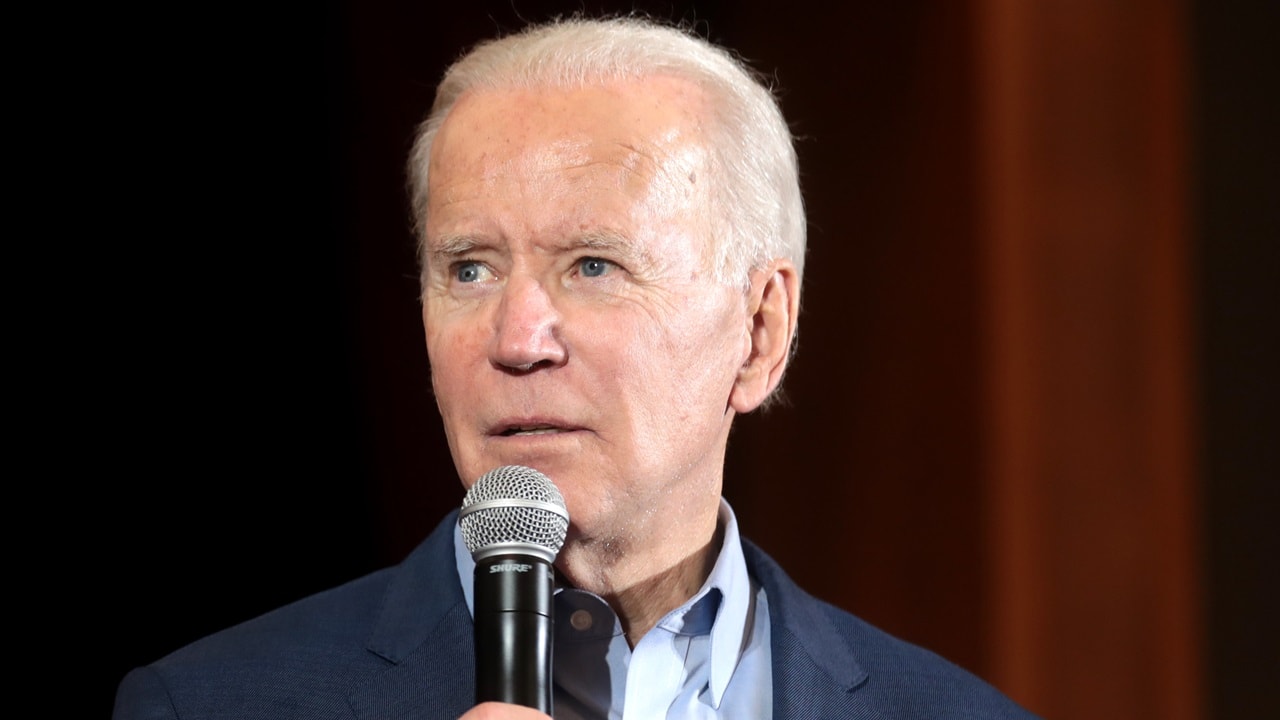

That Weah’s tenure was unremarkable surprised no one. Even his supporters had trouble defending multi-month absences while he traveled on the public dime to the World Cup in Qatar, visited his former residence in Brooklyn, or took time out on the French Riviera. The White House meanwhile, grew increasingly concerned about Weah’s intentions. Transparency International has documented Liberia’s slide in corruption under Weah. Today, Liberia ranks below even Russia, Wagner Group-dominated Mali, and Egypt in Transparency Internationals’ rankings. In part to assuage key political allies, Weah failed to honor his promise to establish the economic crimes court that Liberia’s civil war settlement mandated. On the bicentennial of the founding of Monrovia, National Security Council official Dana Banks warned Weah about the danger of corruption. ““Like many democracies, Liberia still has work to do to seriously address and root out corruption,” she said. “Too many of Liberia’s leaders have chosen their own personal short-term gain over the long-term benefit of their country.” During last year’s US-Africa Leaders Summit, President Joe Biden included Weah in a meeting of African leaders whose stance toward human rights and democracy was most problematic, in theory to warn them about their course of action although Biden’s decision to join them to watch a World Cup match undercut his message.

On October 10, 2023, Liberians went to the polls to elect a new leader. Despite Biden’s statements about his commitment to Africa, the United States was virtually absent. Neither the International Republican Institute nor the National Democratic Institute observed the elections, though NDI assisted other monitors. The Carter Center likewise skipped the 2023 election, though it had observed Liberian elections in 1997, 2005, 2011, and 2017. The US Agency for International Development underwrote some local observations, but these 32 observers had neither the breadth nor the depth to do more than superficial coverage in a country of more than five million people, with thousands of polling stations.

It took Liberia’s National Election Commission more than a week to tally votes, and the results defied belief and logic. Officially, Weah won 43.8 percent of the vote while former Vice President Joseph Boakai took 43.4. Edward Appleton, a relatively unknown figure, won 2.12 percent, and former Minister Lucinee Kamara won just under two percent. Alexander B. Cummings, Jr., the former Coca Cola executive who had led in several pre-election polls, came in a distant fifth.

Such results make little sense. At the peak of his popularity, Weah never won over 38 percent in the first round. His absences from Liberia, public corruption scandals, and rice shortages eroded what little support he had.

But do the ballots lie? In this case, yes.

There were several methods of fraud. When polls closed, workers counted the vote, added it to the tally sheet, and logged the votes each candidate received by hand. Often during this process, workers deliberately marked Cummings’ votes in another space to invalidate them. Such tally errors appear to have almost exclusively affected Cummings. Indeed, invalid votes surpassed votes for Cummings in his strongholds.

Weah, meanwhile, had thousands of supporters deployed around the country with batches and tags identifying them as election monitors and signed by Mulbah Morlu, Jr., the chief of Weah’s Coalition for Democratic Change. Many of these observers had mobile money pro-loaded onto cell phones by the Coalition for Democratic Change headquarters. They then transferred funds into poll workers’ phones who would then change tally sheets, to split votes between Weah, Boakai, and Appleton. The total cost of this scheme was like over 200,000 votes. In theory, poll workers lock tally sheets into ballot boxes before transferring the boxes to magistrates. Workers then break the seal in the presence of observers. While these observers, many affiliated with the Coalition for Democratic Change, would confirm the tally sheet and ballot box number matched, they did not check the votes to ensure the tally sheets reflected the number of votes accurately. They then transmitted these faulty counts to Monrovia. On several instances, they omitted a zero from Cummings’ total, effectively reducing his vote by 90 percent. In some towns, entire extended families voted for Cummings, only to see in the official results that he received just three or four votes.

The brazenness of the fraud was such that over the past six months, the Coalition for Democratic Change trained their poll workers, 80 percent of the total poll workers, in fraud using simulated tallies and databases. Liberians question why in July 2023, Liberian Vice President Jewel Taylor met a senior member of a South Africa-based political consultancy implicated in Sierra Leone voter fraud.

Surprises can happen. Just ask former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. But, the reasons for her 2016 loss made sense: She failed to go to Wisconsin. She did not inspire high turnout in key districts. In Liberia, however, the presidential results make no sense.

For Cummings to lose Grand Bassa County or Maryland County would be as illogical as Democrats losing Berkeley, California, to the Tea Party, or David Duke winning Harlem. Likewise, under no scenario where voting is free and fair and counting is transparent and accurate could Appleton win more votes than Cummings. This would be the equivalent of self-help writer Marianne Willamson beating Hillary Clinton if they went head to head in Arkansas or New York. The sole purpose of putting Cummings in fourth or fifth place is to prevent a runoff that he would dominate. Indeed, exit polls showed Cummings receiving around 30 percent of the votes edging Weah and Boakai, who had about 18 percent each. Appleton likely hovered around one percent, the Liberian race’s equivalent of Rep. Dean Phillips (D-Minn.) who today flirts with a White House run.

If Weah was going to cheat, why not claim a first round victory? He likely realized that would be too obvious and would precipitate a third civil war and lead to immediate sanctions by the international community. Staging a second round fight with the 78-year-old Boakai, a politician who makes Vice President Mike Pence appear charismatic and energetic by comparison, would lead to the same result. Even if anti-Weah protest votes tipped the balance to Boakai, Weah could steal the election; Boakai would simply be too old and unwell to rally the street against the fraud.

Biden’s focus may be on the Middle East, but Africa matters. While African countries had made great strides in recent decades, an epidemic of coups has swept across the continent in recent years: Mali, Burkina Faso, Gabon, Niger, and Sudan among others. Weah’s self-coup against democracy is equivalent to incumbent Faustin-Archange Touadéra’s fake referendum in the Central African Republic.

At issue is not just Biden’s credibility to speak about democracy. As Russian influence grows across the region, Liberia is in the Wagner Group’s sites. Weah not only symbolizes Liberia’s missed potential; he also represents an incompetence and indifference that could drive the country back into ruin and civil war.

A small investment in election observation might have forestalled the current crisis, but silence in the face of Weah’s fraud will not bring peace or stability to the region. Biden may be distracted and his aides late to the game, but it is time both to demand a full, manual recount and perhaps even consider Global Magnitsky Act sanctions on Weah and those involved in the massive election fraud.

Now a 19FortyFive Contributing Editor, Dr. Michael Rubin is a Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI). Dr. Rubin is the author, coauthor, and coeditor of several books exploring diplomacy, Iranian history, Arab culture, Kurdish studies, and Shi’ite politics, including “Seven Pillars: What Really Causes Instability in the Middle East?” (AEI Press, 2019); “Kurdistan Rising” (AEI Press, 2016); “Dancing with the Devil: The Perils of Engaging Rogue Regimes” (Encounter Books, 2014); and “Eternal Iran: Continuity and Chaos” (Palgrave, 2005). The opinions expressed are the author’s own.