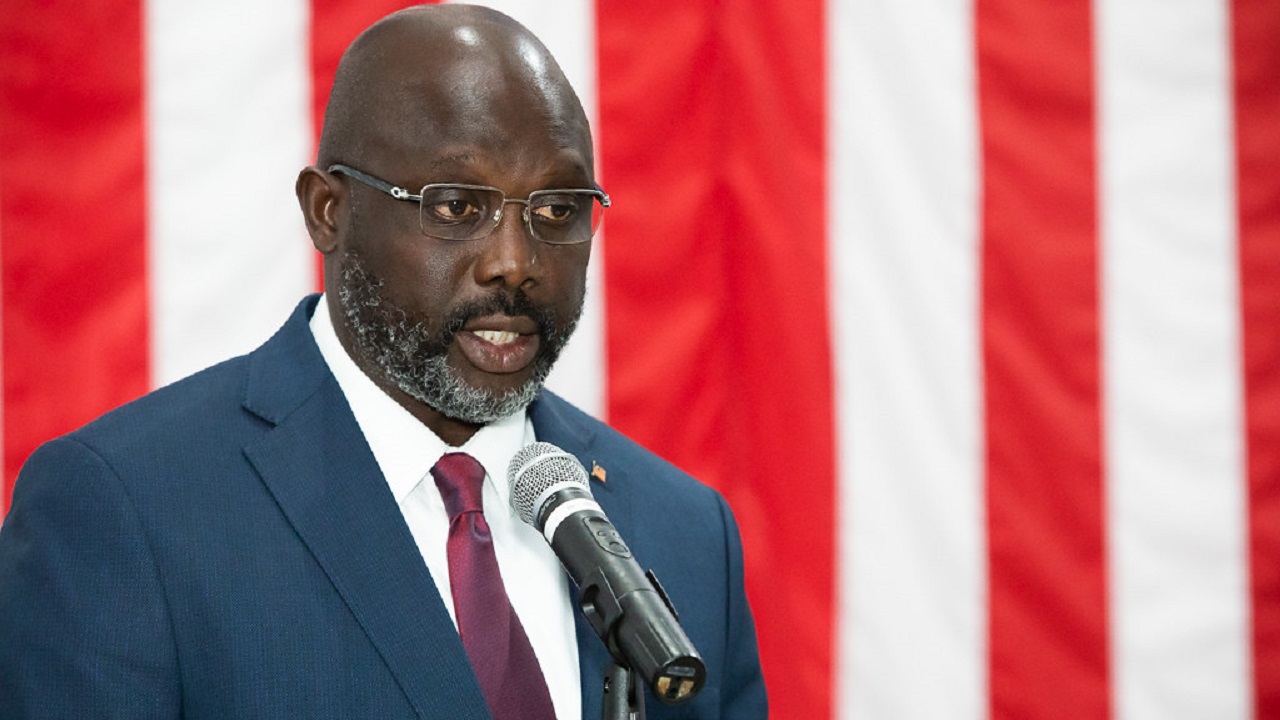

Liberian President George Weah’s trip to New York last month for the United Nations General Assembly was an unmitigated disaster for the West African country’s prestige and interests. The State Department gave Weah and his delegation (with the exception of Finance Samuel D. Tweah, Jr.) highly restrictive visas usually reserved for delegations from rogue regimes. To disprove the reality that Weah received no high-profile meetings, he photobombed U.S. officials in an attempt to deceive the Liberian public. Perhaps partisan supporters accepted the fraud, but such behavior is amateurish and reflects poorly on Liberia at a time when Liberians hope to attract foreign investment.

That was only the tip of the iceberg, however. Visiting Brooklyn, Weah quipped on camera, “after four years, it’s good to be back home.” This is a curious sentiment for an elected leader of another country. President Barack Obama welcomed his return to Kenya and Indonesia, countries in which he respectively had family connections and spent part of his youth, but he never turned his back on the United States as his one true home.

By calling Brooklyn home, however, Weah reignited an earlier controversy over his citizenship. Weah is, without doubt, a Liberian citizen. He was born in Monrovia and attended primary and secondary school in the city, although he dropped out his senior year. After his soccer career took off, he moved in short order to Cameroon, Monaco, France, Italy, England, and the United Arab Emirates. In 1995, FIFA named Weah its player of the year. Ultimately, Weah moved to the United States where he reportedly received US citizenship.

Weah spokesmen demur discussion rather than deny that supposed dual citizenship. While under U.S. law dual citizens must enter or depart the United States with their American passport, it is unclear whether the State Department would make an exception for a foreign head-of-state.

Weah’s situation would not be unique. Former Somali president Mohamed Farmajo renounced his U.S. citizenship in order to bolster his nationalist credentials ahead of his unsuccessful re-election bid. Farmaajo may regret his decision given his loss, but U.S. law does not permit temporary suspension of dual citizenship and so he has no recourse to regain his status nor is it clear that the State Department would even issue him a visa given his record of corruption as Somalia’s leader. Armenian President Armen Sarkissian, meanwhile, resigned earlier this year after journalists reported he held dual citizenship with the Caribbean nation St. Kitts and Nevis.

Weah may prefer to keep his status secret. As with Armenia, Liberian law does not allow the president to hold foreign citizenship. At the same time, the likelihood Weah would lose a free and fair election makes him unwilling to repeat Farmaajo’s actions and risk his ability to return “home” to New York.

While Weah obscures the citizenship question, his reference to New York as home raises another issue: Not only citizens, but also permanent U.S. residents must file U.S. tax returns, even if their assets are abroad. As a permanent resident if not a citizen, Weah would have been subject to such a requirement.

In order to counter perceptions of corruption, most American politicians voluntarily release their tax returns so that the electorate can understand what they own prior to taking office so that they can assess any increase in wealth as an office-holder. Donald Trump, of course, refused to release his returns greatly increasing suspicions that he sought to hid evidence of malfeasance.

It is no secret that Weah’s record is poor with regard to corruption. Under Weah, Liberia’s slide in Transparency International’s Corruption Index has accelerated; the country is now on par with Russia. Weah has also failed to uphold his earlier campaign promise to establish an economic crimes court for Liberia, as legally mandated largely for fear that close political allies may be subject to its jurisdiction.

Releasing his American tax returns to the Liberian press should be a bare minimum for Weah to demonstrate that he has nothing to hide and to recommit himself and Liberia to rule-of-law. He should not resist; it is not only the natural outcome of his New York gaffe, but it is also the right thing to do.