Key Points and Summary: The T-14 Armata, Russia’s next-generation main battle tank, has failed to materialize as a combat-ready platform after a decade of hype.

The Vision: Unveiled in 2015, it promised an unmanned turret, crew capsule, and active protection systems to leapfrog Western designs.

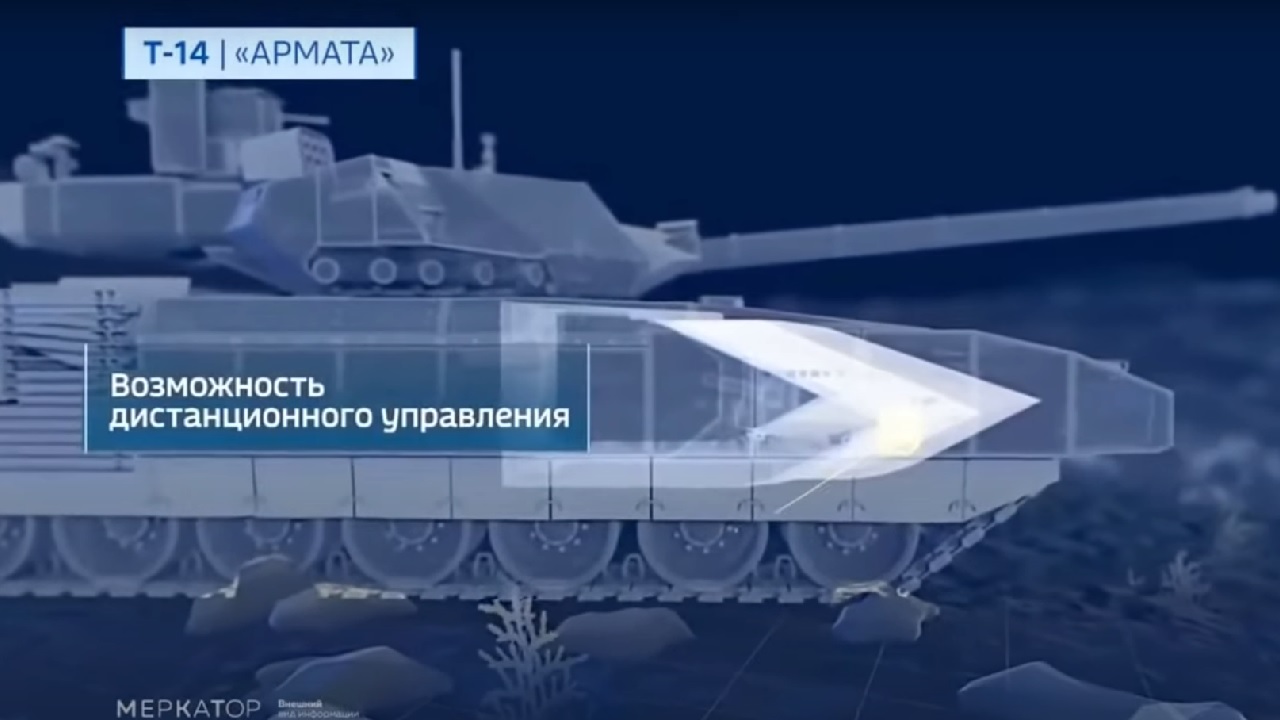

Russian T-14 Armata Tank. Image Credit: Social Media Screenshot.

The Reality: Sanctions, hand-built production lines, and exorbitant costs have limited the fleet to roughly 20 prototypes that are “too valuable” to risk in Ukraine.

The Verdict: The program illustrates a strategic failure; while Moscow chased an exquisite “super tank,” the nature of war shifted to cheap drones and mass attrition, rendering the T-14 obsolete before it ever fought.

The Russian Army’s T-14 Armata Tank in 1 Word: Failure

In early 2015, the T-14 Armata – Russia’s next-generation main battle tank – finally appeared in public view during Moscow’s Victory Day parade.

It was hailed by the Kremlin as the future of armored warfare, with Russia claiming it would redefine battlefield dynamics with its unmanned turret, advanced active protection, and a digital networked crew capsule.

And yet, more than a decade later, the T-14 remains conspicuously absent from frontline combat in Ukraine and largely undelivered – at least, in any meaningful numbers.

The tank didn’t turn out to be a battlefield game changer, after all. Plagued by cost overruns, technical setbacks, and production failures, the T-14 Armata is real – but it’s also a good example of how quickly plans can change when sanctions kick in.

Russia T-14 Armata Tank. Image Credit: YouTube Screenshot.

A Next-Gen Tank On Paper

The T-14 project was launched to replace Russia’s aging T-72, T-80, and T-90 fleets and to leapfrog Western and Chinese designs. A tall order, yes – and indeed one that Russia hasn’t been able to fulfill. On paper, at least, it’s impressive.

The tank boasted several dramatic innovations, including a crew housed in an armored capsule, an unmanned turret equipped with a 125 mm gun, and the Afganit active protection system, which protects against kinetic and chemical energy threats.

Promoted as a fourth-generation main battle tank, the Kremlin said the T-14 would return Russia to the very height of its tank development.

And yet, early testing revealed that the reality quickly diverged from what was promised. Reports flagged serious reliability problems, component durability issues, and doubts about whether the proposed advanced features were ever fully operational.

Prototype of Russian main battle tank T-14 Armata, view from above, Victory parade Moscow 2015.

By late 2023, Ukraine’s intelligence service estimated only about twenty T-14 units had been produced – and none had pushed full state trials or even been adopted in mass service. The T-14 was a flop – but Russia’s own state-owned defense conglomerate had a different story. They claimed that the tank was simply “too valuable” to deploy in sustained combat.

That might be true, but the fact that Russia knows it could not replace the tanks should they be lost on the battlefield proves that the T-14 is little more than just an interesting, finite asset that is about as vulnerable on the battlefield as any other tank.

The contrast between the advertised capabilities of the T-14 and its actual status is pretty stark. Although the platform is still seen in marketing materials, there has been no real serial production, and operational deployment and verified combat performed suggest it’s merely a symbol at this point.

Why the Armata Program Collapsed

The apparent reason Armata failed is this: sanctions.

But there’s more to the story, too. In fact, several interlocking factors account for the T-14’s failure to materialize as intended.

Let’s first look at costs and priorities: the unit cost of the T-14 was estimated at several million dollars – far higher than Russia had budgeted for.

The increase in cost meant that it couldn’t actually be sustained at scale. And, faced with heavy losses in Ukraine and urgent demands to ramp up numbers, Moscow opted to modernize its legacy platforms, such as the T-90, rather than invest in an expensive and unproven system. A tough choice, but a logical one.

The domestic production line for the T-14 never actually achieved accurate serial output, in large part thanks to sanctions and industrial bottlenecks.

There was no assembly line. Yes, really: every vehicle was hand-built like a luxury car. Sanctions and supply-chain constraints further hindered the manufacture of key components and high-end electronics required for the platform.

T-14 Armata. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

But even if Russia had been able to assemble more of the tanks before the sanctions really kicked in, it might not have changed the reality on the battlefield. Even when the war in Ukraine created a burning need for armored vehicles, Russia hesitated to commit T-14 units to the frontline for one worrying reason: they were vulnerable.

With the rise of automated systems, drone warfare, and long-range combat, those tanks may have proven as vulnerable as older units – and losing tanks built pre-sanctions would mean replacing them with older tanks.

That wouldn’t have made sense.

For more than a decade, the T-14 Armata has embodied Russia’s ambition to leap ahead of the West in tank design and warfare.

But it failed.

It failed so spectacularly, in fact, that had Russia even found a way to make the T-14 properly operational, the nature of combat would have changed before they truly became relevant, anyway.

The reality is this: the world is slowly moving away from tank warfare.

About the Author:

Jack Buckby is a British author, counter-extremism researcher, and journalist based in New York. Reporting on the U.K., Europe, and the U.S., he works to analyze and understand left-wing and right-wing radicalization, and reports on Western governments’ approaches to the pressing issues of today. His books and research papers explore these themes and propose pragmatic solutions to our increasingly polarized society. His latest book is The Truth Teller: RFK Jr. and the Case for a Post-Partisan Presidency.