In the pernicious culture wars we are currently living through there is perhaps no quicker route to cancellation than to speak well of ‘empire’. Nevertheless, in the arena of international relations, the term is widely used as shorthand to refer to dependent relationships within a hierarchical international order. Describing Australia or Japan, for example, as members of the ‘U.S. empire’ may cause a few collars to be adjusted in search of more politic euphemism, but it’s hardly controversial. There is, therefore, something of a conceptual disjunct between the prevailing cultural hostility to empire and the widespread acceptance of what the term implies. Both, however, rely on a simplistic notion of empire itself, the former as unaccountably evil, the latter as a universal category. The nature of the various empires themselves, historical and contemporary, goes largely unexamined.

Empire as Order

The case was recently made by Robert Kaplan in The Afterlife of Empire that, setting aside moral criticisms of various forms of imperial domination, empire is the historically normal form of political organization. This is true, he argues, throughout history and throughout the world, and we need to recover a sense of that in order to better understand the naturally hierarchical world of international relations. The pejorative connotations of empire, he says, come mostly from its association with cruel European powers, but empires were never exclusive to Europe, even if European powers claimed an exclusive monopoly for themselves for a time. Outside of Europe, many states are accustomed to both navigating and accommodating the interests of regional great powers.

Kaplan also argues that the real challenge of today’s empires (in which he includes Russia, China and the U.S., along with the EU and some regional powers like Turkey) is how well they respond to the many prevailing global challenges, making the point that while once empires declined over decades, that may no longer be the case. In arguing, however, that empire is the normal form of international organization Kaplan is really making an argument about how the U.S. should behave in the world.

This kind of argument is not new. Niall Ferguson famously made the case for greater U.S. commitment to the duties of empire with his 2003 book Empire: The Rise and Demise of The British World Order and its Lessons for Global Power (reviewed here). More recently Salvatore Babones offered a structural defense of U.S. hegemony in his American Tianxia: Chinese Money, American Power and the End of History (summarized here). Both these accounts concentrate on the US as an imperial power as distinct from the empire that is its consequence. And herein lies an important distinction; there is a difference between an empire, and the imperial power which brings it to life. This distinction is often overlooked, but it is important because if we accept that empires ultimately reduce to geographical arenas through which imperial power is relayed, then the geography becomes much less important than the source of the power so relayed. Moreover, the empire itself is not the subject, but the object of imperial power.

Empires are not States

This confusion between subject and object often produces an analysis that is focussed on the empire, rather than the imperial power, much as Kaplan refers to the period when the U.S. and USSR eclipsed the collapsing British and French empires in the Post-WWII period. In fact, the French empire had lost its motive power in the middle of the 19th Century, and the British sometime after that. Both empires had maintained their formal structure and exhausted themselves in their own defense in the two world wars, but the industrial strength of the US had long surpassed them. The US joining the allied war effort in 1941 restored the motive power of the West, after which it was relayed through many of the same channels once dominated by the British. In other words, the motive power of US industry found its imperial relays when Winston Churchill put out the distress call.

The difference between the US and British approach to empire, was merely the institutions through which power was relayed. The British empire in its later years, as an industrially weaker power by comparison with the US and Germany, relied on formal commercial monopolies and exclusive trade privileges enforced by the Royal Navy and Royal Charter companies operating under English common law. The US on the other hand, did not require commercial monopolies as it already had the most competitive and advanced industry and agriculture. The US therefore had no need of the formal structures of empire that the British relied upon as its power waned. Indeed, the US demanded that the formal monopolies be dismantled.

In both cases, however, the empire is always the field of operation for the imperial center, not merely an expanded version of the imperial state. The same is always true throughout history. Whenever an empire emerges it is a consequence of a new combination of arms and ideas that pushes into the space of a crumbling old order, creating a new hierarchy with a newly vigorous centre relaying its power outwards. When the British Empire rose in the 17th and 18th Centuries before coming to dominate the 19th, it was built on the strength of a newly centralised state born of the Glorious Revolution, which laid the foundations for the industrial revolution that followed. The motive power this gave rise to had its competitors, but British industry and commerce sustained unparalleled colonial expansion because of the huge surpluses that came with mass production and eventually steam power. Just like the US in the 20th Century, however, early British imperial expansion relied upon dismantling trade restrictions not erecting them, first in India, then in China.

Although, therefore, Kaplan is probably right to say that empire is the historically normal form of international organisation, it is important not to mistake empires as strategic actors in their own right, rather than the imprint of strategic action by vigorous and rising imperial powers. Furthermore, that if an imperial centre loses its motive force, then it becomes merely the next crumbling historical edifice that is made subject to the strategic aspirations of new and vigorous powers.

Unfinished Empire:

One of Kaplan’s references in the above-linked article is to the work of John Darwin, historian of the British Empire. Darwin’s most interesting account of the British Empire comes in his volume The Unfinished Empire, in which he says this, which is worth quoting at length:

“(The British Empire) was also, and crucially, an unfinished empire. When we stare at old maps of the world with their masses of British imperial pink, it is easy to forget that this was always an empire-in-making, indeed an empire scarcely half-made. As late as 1914 (sometimes imagined as the ‘high noon’ of empire), the signs of this were everywhere: in the derelict state of some of Britain’s oldest possessions; in the exiguous strands of settlement that made up Canada and Australia; in the skeletal administration of tropical Africa, soon to be even more skeletal in the 1930s depression; in the chronic uncertainty over what kind of Raj would secure British control and appease Indian unrest; in the constant avowals that there would be no further imperial expansion, and the no less constant advances, a pattern that continued even after 1945; in the fuming and fretting of imperialists at home that public opinion was not imperial-minded enough. Indeed, the most ardent Edwardian imperialists believed that far from constructing a durable edifice that needed only periodic attention, the Victorian makers of empire had bequeathed their successors little more than a building site and a set of hopelessly defective plans.”

Why this matters is above all because the last decade or so has seen the U.S. gripped by a confusion of purpose. The post-Cold War order of U.S. supremacy has given way to a more confusing world of regional and global challengers, and the US population has become resentful of the burdens, both military and economic, expected of them in order to maintain an imperial vanity project that benefits them no longer. It is as if those who govern the US–Kaplan included–are fuming that the population is not ‘imperial minded enough’ and with the removal of President Trump look forward to ‘restoring US leadership’ around the world.

This would be a mistake. Leadership is either exercised or it is absent. It is discovered in the behavior of other states, not in the rhetorical claims made on behalf of one’s own. Most of all, although Empires look impressive when drawn on maps, they are ultimately ephemeral and dependent upon the economic and technological vigor of the imperial center. The map is less important than the motor, and the most important work in sustaining US influence internationally, lies not in leading international institutions, signing trade deals, working with allies or adjudicating war and peace but in restoring the motive power of the US economy, and relearning the firm but quiet patriotism that once liberated both Europe and Asia and took the US to the Moon. Fix that and all else follows.

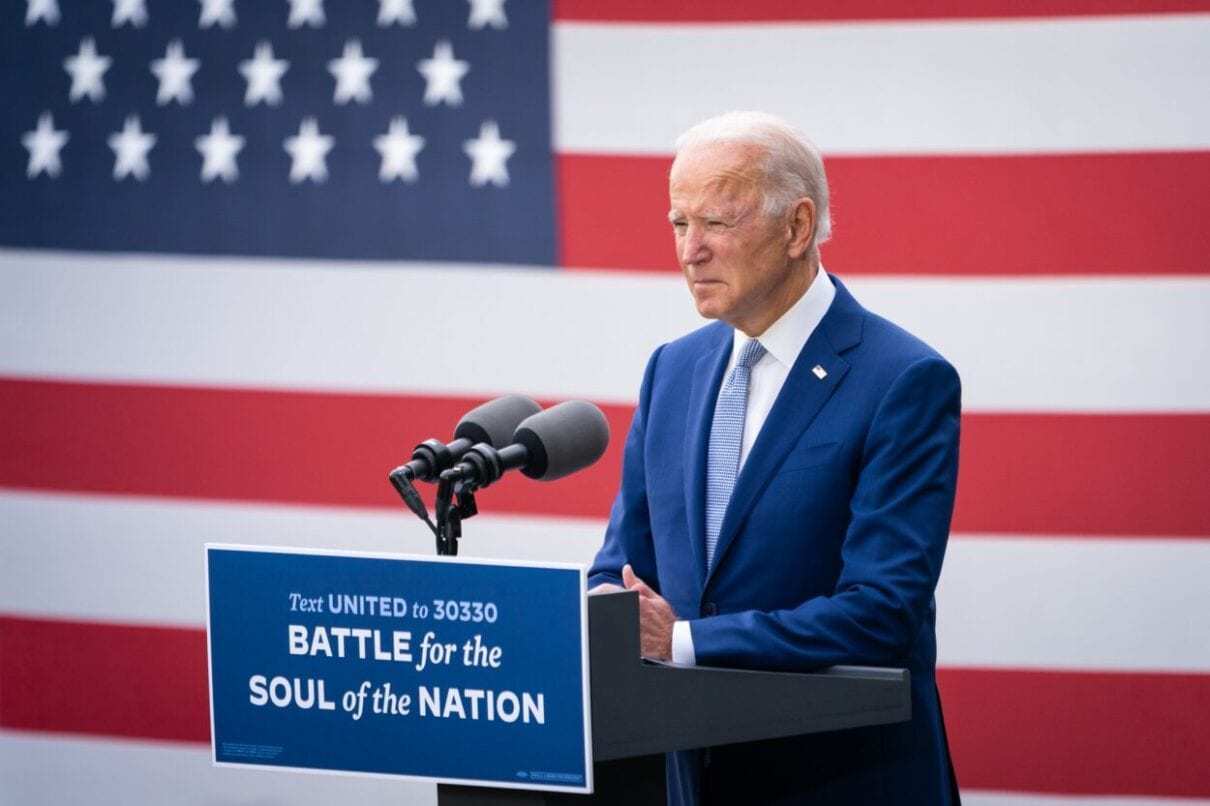

Donald Trump, for all his shortcomings, understood this. Does Joe Biden? More importantly, does the phalanx of foreign policy specialists who framed the U.S. as ‘the indispensable power’ and wasted thousands of lives and the industrial strength of the U.S. economy on wars they now never mention, and on the economic development of China which openly mocks their naivety? That is a much harder question to answer. Kaplan, for his part, makes a good case that some version of empire represents the normal form of international relations. But in not distinguishing between the map that shows an empire’s extent and the motor that sustains its dynamism he treats the US empire as something that needs defending with treaties, alliances and leadership, as opposed to an unrelenting commitment to technological advance and an economic dynamism spread widely among its own population rather than that of its rivals. In doing so, like the British imperial mandarins before him, he risks regarding the U.S. empire as indispensable, right up to the point where erstwhile allies start to dispense with it.