Increased staffing, personal protective equipment and testing contributed to the mounting financial crisis that could jeopardize the care of thousands of older Americans, many of whom are women.

*Correction appended

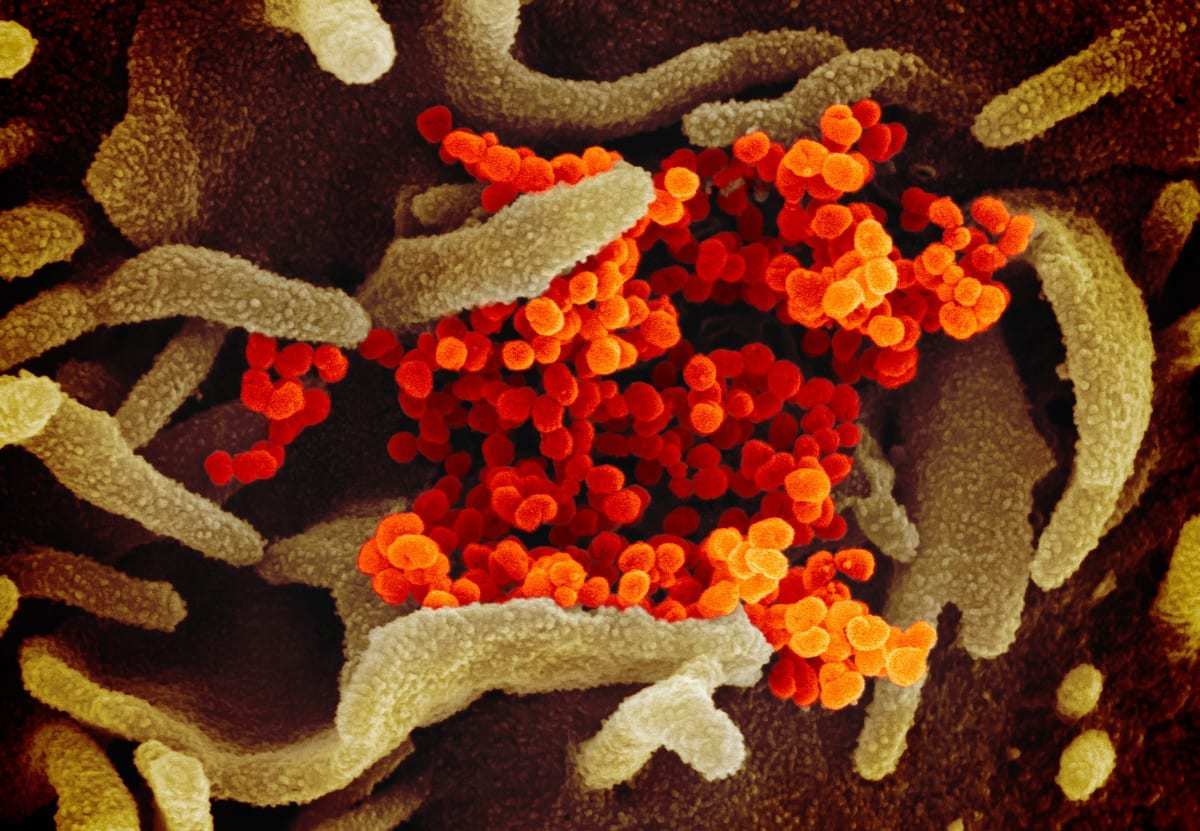

The United States recorded its first COVID-19 death in February 2020 as the virus swept through a Washington nursing home. Within one year, the country has reported more than 136,000 coronavirus deaths linked to long-term care facilities — more than one-third of all coronavirus deaths in the country. Now, the nursing home industry faces a financial crisis.

About 90 percent of nursing homes are operating at a loss or less than a 3 percent profit margin, and more than 65 percent said they will be forced to close within the year due to overwhelming pandemic-related costs, according to a recent survey conducted by the American Health Care Association and the National Center for Assisted Living.

Lisa Sanders, a spokesperson for LeadingAge, an association of nonprofit health care providers dedicated to older adults, said the country’s aging services industry was not equipped to combat the virus.

“We’ve never seen a pandemic like this before,” Sanders said. “There was so much that wasn’t known at the beginning. As the pandemic wore on, it became clear that personal protective equipment — critical resources necessary to do battle — were needed in volumes that had not been budgeted for.”

Many of the country’s 15,600 nursing homes were forced to hire additional staff, pay current employees overtime, buy personal protective equipment and provide regular testing as more than 1.1 million residents and employees — the majority of which are women — have been infected.

The American Health Care Association and National Center for Assisted Living, which represents more than 14,000 nursing homes and other assisted living communities, released a statement on Wednesday calling on Congress to approve $100 billion in relief funds and dedicate “a substantial portion” to long term care.

Last March, lawmakers passed the CARES Act, which distributed tens of billions of dollars in federal aid to help nursing homes and other health care providers. That relief money never covered the full cost of care during the pandemic, Sanders said, and the costs continue.

Many providers rely on short-term residents, including those recovering after surgeries, to cover the cost of long-term residents, Sanders said. That funding stream quickly dried up at the beginning of the pandemic as hospitals halted surgeries and families grew more and more reluctant to send their loved ones into nursing homes.

“There needs to be a rethinking of how we as a country approach long-term care financing,” Sanders said. “Quality care costs money, and we have to find a way to pay for it because our current system does not.”

Quality care costs money, and we have to find a way to pay for it because our current system does not.

Lisa Sanders, a spokesperson for LeadingAge, an association of health care providers dedicated to older adults

Many nursing homes across the country — including in California, Indiana, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Colorado, Kansas, Michigan, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New York and Rhode Island — have already permanently closed their doors in recent months, leaving some of the most vulnerable without the care that they need during the pandemic.

“What happens if nursing homes fail?” Sanders said. “Well, people will have to find other types of care. Maybe people will live in assisted living, but it’s not covered by Medicaid, so if you’re poor you won’t have that option.”

As nursing homes close, family caregivers — overwhelmingly women — will likely feel the additional strain. Almost 42 million Americans, or 16 percent of all adults, serve as caregivers for relatives 50 and over. According to data compiled by the AARP, most of the people doing this unpaid, labor-intensive work are women, and, on average, they are just shy of 50 themselves. Many have jobs outside the home, or are also primary parents for young children.

The 65-and-older population is the nation’s fastest growing demographic in the past decade, driven by aging Baby Boomers and lower birth rates, according to 2019 U.S. Census Bureau estimates. Because women tend to live longer than men, there is a stark difference in population at the 85-plus demographic, with 4.2 million women in the United States versus 2.3 million men.

“We don’t tend to think about long-term care until we need it,” Sanders said. “Long-term care has traditionally not gotten the kind of recognition it deserves for its vital role in the health care system. I hope that as a result of the pandemic, that changes. People are going to age and they’re going to need help.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article misquoted Lisa Sanders on assisted living funding. Assisted living is not covered by Medicaid.

Originally published by The 19th