The Lebanese pound is in freefall. While officially the government pegs it at 1,500 to the U.S. dollar, the black market rate now approaches ten times that. Lebanese have always understood the extent to which their elites diverted or stole the billions of dollars the international community and World Bank provided their government, but the decline in their national currency now challenges daily life in a way unseen since the 1975-1992 civil war. Two weeks ago, fistfights erupted at supermarkets in Nabitiyeh, a southern Lebanese town that is in the Hezbollah heartland. A week ago, there were near-riots at two different locations of Rammal, a Hezbollah-owned supermarket chain, in the Dahieh, Hezbollah’s southern Beirut stronghold, as shoppers fought over subsidized food.

This past weekend, the situation escalated again. Lebanon’s lifeline is the highway that runs along the coast from the Israeli border in the south to the Syrian frontier in the north. While diplomats and journalists often describe southern Lebanon as Shi’ite, the demography is actually more complicated: The highway runs through a few non-Shi’ite towns a few miles south of Beirut. In recent days, residents have blocked the highway at Naameh, a Sunni and Christian town, 12 miles south of Beirut. Sunnis have also come down from the mountain town of Barja to block the highway at al-Jiyeh, a town six miles south of Naameh. Blocking the highway not only is a visible protest—the equivalent of cutting off travel on I-95 on the east coast of the United States—but it more specifically undercuts the ability of Hezbollah to distribute goods and money which it receives at Beirut’s port, airport, or across the Damascus-Beirut highway to its supporters in the south.

This may be why Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah has grown so alarmed. On March 18, he declared, “You, the ones blocking the road and causing people to go hungry, you are increasing poverty, you are putting the country at the tip of civil war… I tell the good people being humiliated on certain roads to be patient because we will find a solution.”

During his speech, a Barja resident and young activist named Jamal Terro tweeted, “Nasrallah was talking in his speech about roadblocks when he is blocking the whole country from breathing.” Hezbollah responded by broadcasting his image, address, and phone number across their social media, basically the 21st century equivalent of putting a bounty of Terro’s head. Terro, for his part, has remained defiant. He urged Hezbollah to recognize they had a choice: to remain calm or be choked “with no Russian jets able to come to the rescue.”

The back-and-forth illustrates how jumpy Hezbollah is, its vulnerability, and the increasing willingness of locals, even after the murder of Lokman Slim, to stand up to the group. At the same time, they remain spread thin with large numbers still in Syria. Hezbollah’s diminishing ability to bribe and deliver is reducing their influence in the Lebanese Armed Forces.

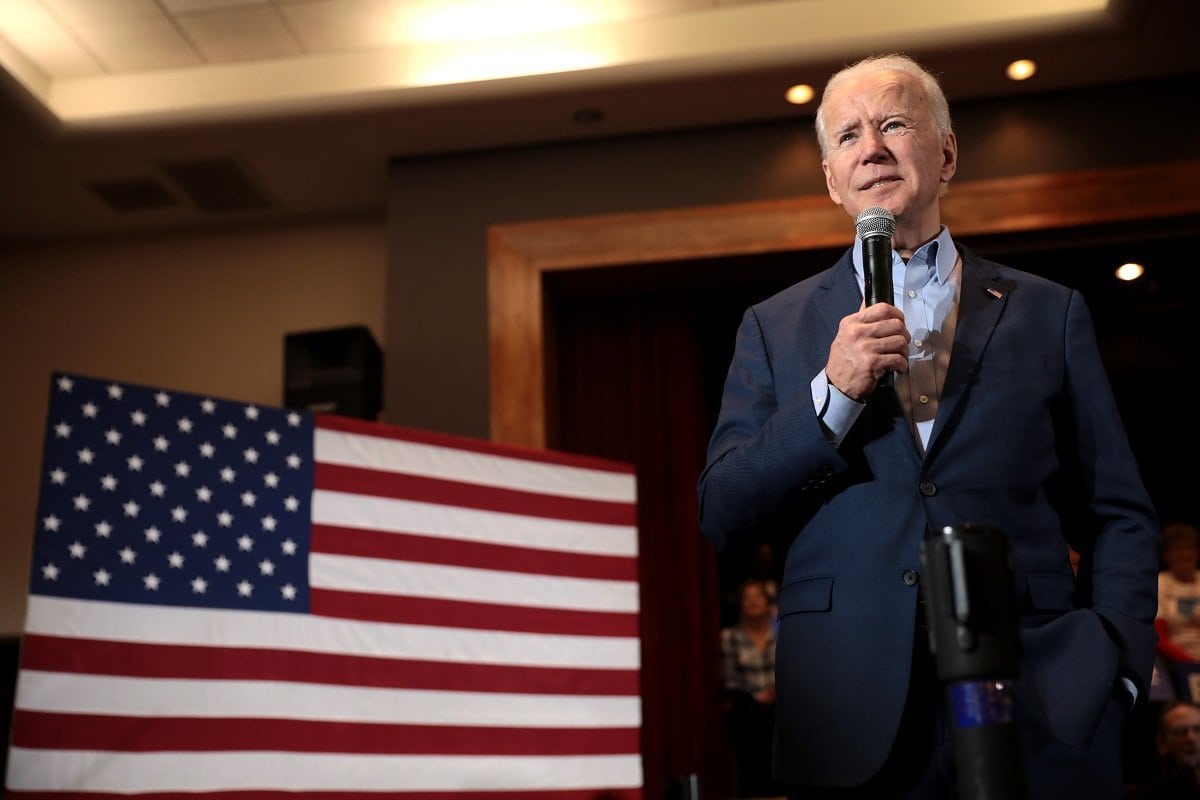

There is a school of belief within the State Department that the United States should release money to Iran or enable the Iranian government to receive money frozen elsewhere in order to jumpstart diplomacy. The irony is not only that to provide such funds to Tehran reduces American leverage when leverage is most important, but also that such monies would increase the resources Hezbollah has at its disposal when it has hit a road block and when Iran’s support for proxies is in the American crosshairs. In effect, President Joe Biden and Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s diplomatic strategy toward Tehran would empower Hezbollah to preserve diplomacy to discuss its demise. This is nonsensical and evidence of a policy untethered to reality and counterproductive to end goals.

It is time for Biden and Blinken to reconsider the ramifications of their Iran policy now, lest they snatch defeat from the jaws of victory.