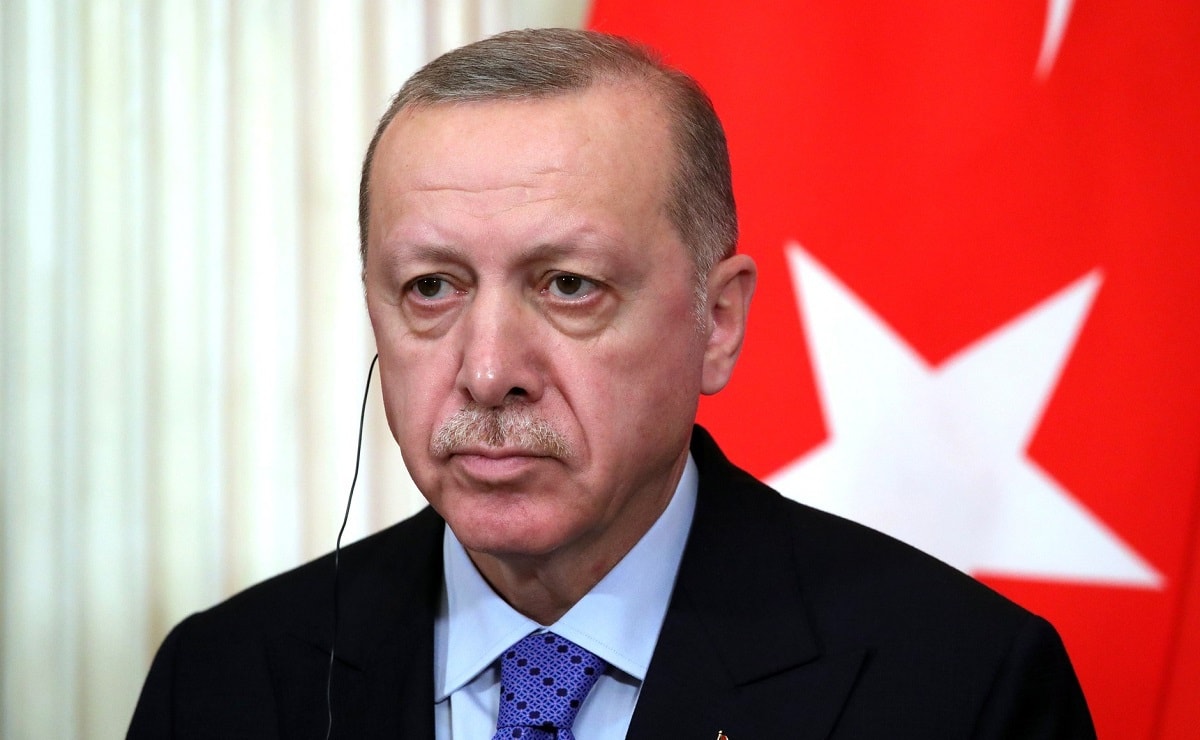

Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan wants to build a canal. Called a “crazy project” by none other than Erdoğan himself, the Kanal İstanbul would link the Black Sea with the Sea of Marmara, and from there through the Dardanelles to the Mediterranean. Its main purpose would be to bypass the busy Bosporus, the dangerously overcrowded strait that bisects the teeming metropolis of Istanbul. It would also upend the 85-year-old Montreux Convention that demilitarized the Bosporus and, by extension, the entire Black Sea basin.

Erdoğan’s unlikely goal is to finish the megaproject—on which the first shovel of sand has not yet even been turned—in time for the centenary of modern Turkey in 2023. A more reasonable goal would be to start work in 2023. Either way, the symbolism is important: the modern Turkish republic was proclaimed on October 29, 1923 by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. The 1936 Montreux Convention was one of Atatürk’s final achievements before his death two years later, and the final brick in the edifice of Turkish independence. But it didn’t quite liberate Turkey entirely from international oversight of the Bosporus and Dardanelles. Erdoğan’s canal would.

It is not too much to say that Atatürk created modern Turkey; the very name Atatürk is an epithet, meaning “father of the Turks.” Turkey emerged from the ruins of the Ottoman Empire, which fought World War One on the losing side. At the end of the war, the 1919 Treaty of Versailles imposed severe penalties on the German Empire, while the associated treaties of Saint-Germain and Trianon broke up the Austro-Hungarian empire entirely. The 1920 Treaty of Sèvres was supposed to do the same for the Ottoman Empire, but Turkey’s greatest general balked at its extraordinarily harsh terms. Mustafa Kemal, later known as Atatürk, reorganized the remnants of the Ottoman army and reopened the war.

As a result, the Treaty of Sèvres never went into effect. If it had, Thrace and Smyrna would now be part of Greece, northeastern Turkey would be part of Armenia, and southeastern Turkey would have held a referendum to create an independent Kurdistan. The treaty even stipulated that, in the event of Kurdish independence, the areas that now form the autonomous Kurdish regions of Iraq would have joined the new country. And the entire zone around the Bosporus and Dardanelles would have become a neutral Straits Zone governed by an international commission. The much-maligned Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 would hardly have mattered, since the postwar Treaty of Sèvres upended many of its most important provisions.

Atatürk fought tooth and nail in a series of bloody campaigns to eject Greek, Armenian, British, and French forces from the territory of what is now Turkey. In a war that saw terrible atrocities on both sides, he ultimately prevailed, and gained recognition of Turkey’s modern borders in the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne. An associated Straits Convention set up an international commission to govern access to the Dardanelles and Bosporus. It was the one remaining imposition on Turkish sovereignty, and it stuck in Atatürk’s craw.

Although the Montreux Convention now has all the dignity of great age, any of the parties to the convention retain the power to overturn it with a mere two years’ notice. That gives Erdoğan the legal basis under which to regain authority over the straits while at the same time opening his new canal, forcing ship traffic to divert from Istanbul’s city center to the nearby suburban waterway. Geopolitics aside, there are good arguments for making the change. The Bosporus is a narrow, winding waterway, crisscrossed by ferries, and unwieldy for today’s enormous oil and LNG tankers. Absent the politics, it would make a lot of sense to divert commercial freight around it to an industrial canal. The Bosporus could become the preserve of cruise ships and pleasure boats, a renewed tourist zone in the heart of Istanbul.

But geopolitics, domestic politics, and national pride inevitably come into play. At the time the Montreux Convention was signed, Atatürk was aligned with the Soviet Union, which had aided Turkey in its war of independence. The convention’s terms accordingly favored Soviet interests, protecting the Soviet Union from outside naval interference while allowing Soviet ships (mostly) unfettered access to the Mediterranean. After Atatürk’s death, his successors entered into an uneasy alliance with the United States, ultimately turning Turkey into NATO’s strategic southern flank. In a time of high Cold War tensions, however, the convention was suffered to remain in force.

As Erdoğan returns Turkey to more cordial relations with Russia (despite multiple points of friction), the prospective Kanal İstanbul would give him a major bargaining chip—but only if he abrogates the Montreux Convention. Russia has strongly hinted that it is opposed to any revision of the convention. Erdoğan credibly maintains that the new canal would not be covered by the Montreux Convention, but this is beside the point: ships transiting the canal would still have to pass through the Dardanelles, which (in addition to the Bosporus and the Sea of Marmara) are unambiguously included. More provocatively, Erdoğan has suggested that he might revisit the convention itself—which, with two years’ notice, is entirely within Turkey’s right to do.

With the geopolitics on hold (for now), the domestic politics of the proposed canal have turned hot. When 104 retired Turkish naval officers issued a statement criticizing Erdoğan for calling the Montreux Convention into question, the government responded by arresting ten of them and summoning four others to report to the police. Having faced a failed coup attempt in 2016, Erdoğan is taking no chances with the Turkish military’s disaffected officer corp. Istanbul’s opposition Republican People’s Party mayor, Ekrem İmamoğlu, also opposed the canal project. Officials from Erdoğan’s own Justice and Development Party have pointed out that the canal project does not fall within the remit of the city mayor.

But as the 2023 centenary approaches, the decisive consideration in determining the future of Erdoğan’s canal may be national pride. The Montreux Convention is the last vestige of foreign interference in Turkey’s territorial integrity. Although often labeled a neo-Ottoman, Erdoğan is every bit as much a Turkish nationalist as was Atatürk. His nationalism may be religious where Atatürk’s was secular, but just like Atatürk, he wants to lead a strong, nationalist Turkey, not a tolerant multinational empire. Just like Atatürk, he has suppressed the Kurds, fought the Armenians, and antagonized the Greeks. And just like Atatürk, he resents the curtailment of Turkish sovereignty represented by the internationalization of the Bosporus.

Unlike Atatürk, Erdoğan is in a position to do something about it.