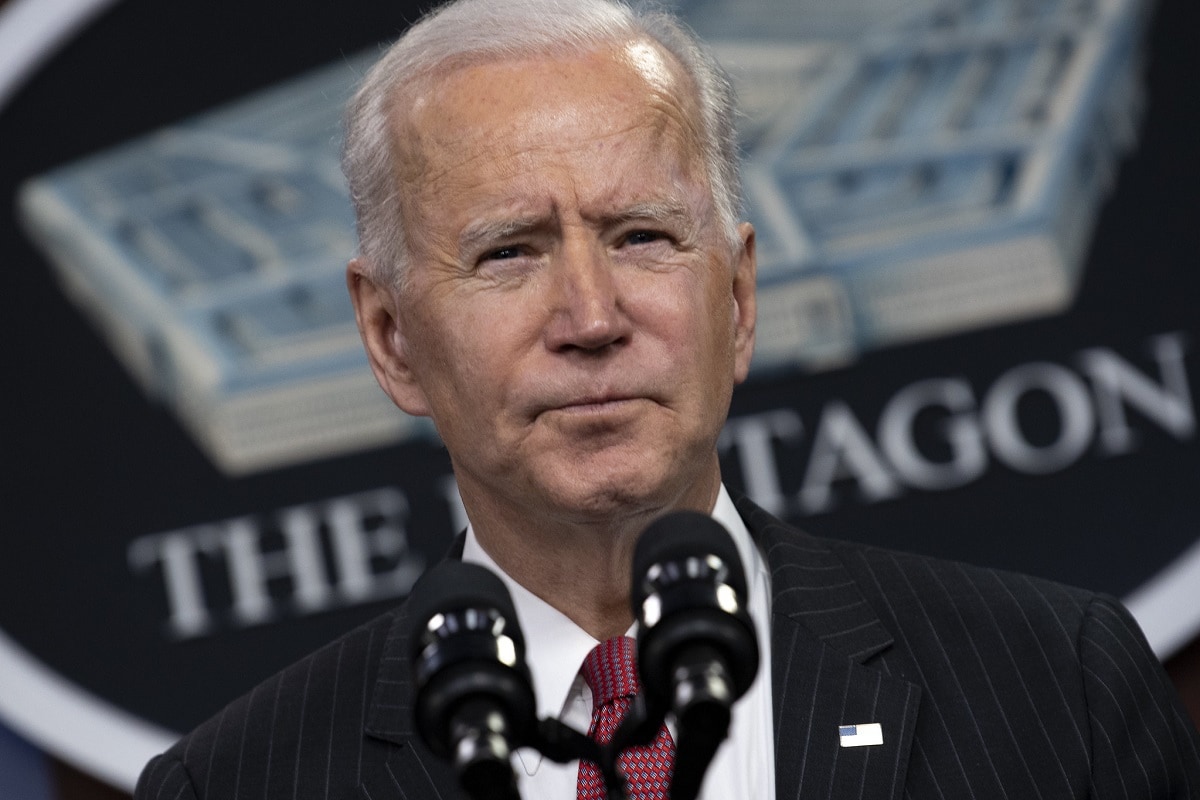

President Joe Biden is pushing forward with talks to return to the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) with American diplomats joining diplomats from Iran, Russia, China, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and the European Union next week in Vienna. Sadly, it seems the U.S. willingness to release more money seized or frozen under the sanctions appears to have greased the talks.

Within the United States, partisans can rehash their assessments of whether the deal worked. Veterans of the Obama administration and many left-of-center advocacy groups like the Ploughshares Fund or the Arms Control Association argue it placed unprecedented restrictions on Iran. Critics—myself included—counter that by pointing at both the deal’s loopholes and how it reversed decades of more rigorous non-proliferation requirements.

As the Biden administration, re-engages, it should consider lessons learned from the JCPOA era.

First, the JCPOA was not a treaty or an executive agreement, but rather only a loose, political commitment. “The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) is not a treaty or an executive agreement, and is not a signed document,” Julia Frifield, assistant secretary for Legislative Affairs under Secretary of State John Kerry explained in a letter to then-Representative Mike Pompeo. While Obama-era alumni castigate President Donald Trump for failing to adhere to their political agreement, the fact that they had shredded a similar Bush-era Iran-related political agreement with European allies undercuts their standing to make such arguments.

There are no shortcuts: If any nuclear deal with Iran is going to stick, it must be a ratified treaty with broad bipartisan support. There is no evidence, however, that Biden, Secretary of State Antony Blinken, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, or Special Envoy Rob Malley have any intention to reach across the aisle or recognize that objections to their approach rest not only in partisanship but also in honest disagreement. Their failure to address such arguments head-on combines arrogance with a lack of self-confidence in their arguments. Symbolically, too, it is troubling that Biden’s team appears more willing to negotiate with Iranian officials than with Republicans in Congress.

Second, leverage matters. Secretary of State John Kerry hemorrhaged advantage both by paying Tehran billions of dollars to come to the table and by showing that the United States was unwilling to walk away from the table. In effect, Kerry signaled to the Iranian regime that the process of negotiation could be more lucrative than any final deal. Few understand the way Iranian hardliners think than Wang Xiyue who was their involuntary guest for more than three years. Generosity will only encourage further demands or weaken controls.

Details also matter. Because the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps dominates the Iranian economy, any incentive that pumps money into Iran absent controls to ensure such sanctions relief or new investment does not benefit the Guards’ industries strengthens regime hardliners at the expense of ordinary Iranians. The choice between JCPOA and nothing is a false one. Iran, after all, is still subject to its nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Safeguards Agreement in which it remains in violation. That Iranian leaders promised Kerry to act in conformity with the Additional Protocols of the Non-Proliferation Treaty without formally ratifying it and enshrining their commitments to it in law remains one of Kerry’s biggest blunders.

Third, it is crucial to stop misreading Iranian politics. Blinken, Sullivan, and Malley may believe they are empowering reformers ahead of Iran’s forthcoming elections, but they misunderstand Iranian factionalism by mirror imaging their own sense of Western politics. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei remains the gatekeeper to Iranian politics. In his March 21 Nowruz speech, he articulated the qualities necessary for any future president. The Revolutionary Guards, meanwhile, have outlined their own role in guaranteeing such elections conform to the system’s needs. Reformists do not want to change the system nor would the Revolutionary Guards allow them to do so. The factional differences are much more of style than substance and represent an elaborate game of good cop-bad cop.

This is one reason why so much covert nuclear activity has occurred under reformists. Another is that elected political leaders inside the Islamic Republic do not hold sway over security and military policy. If the United States wants a lasting agreement with the Islamic Republic, it must negotiate with the Supreme Leader and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. Perhaps they would refuse, but their refusal also provides a barometer into their sincerity to settle disputes.

Unilateral incentives to Iran may assuage the Democrats’ progressive base, but they will neither change Iranian behavior nor resolve concerns about its nuclear ambitions that have only grown since the initial JCPOA, Iran’s investment in ballistic missiles, or Tehran’s efforts to hide its nuclear archives. As importantly, a rush into negotiations will reverberate well beyond Iran as states like North Korea recognize that defiance pays. There is power in a do-over if only to learn lessons from previous stumbles and plug earlier loopholes.

Unfortunately, it appears that Biden, Blinken, Sullivan, and Malley prefer to double down on past mistakes rather than learn from them.

Michael Rubin is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a 19FortyFive Contributing Editor.