Today’s strong GDP and employment numbers can leave little doubt that the U.S. economy is well on the mend from last year’s Covid-induced recession.

With almost 6 ½ percent GDP growth in the first quarter and with new jobless claims at their lowest level since the pandemic’s onset, there is every prospect that by mid-year the U.S. economy will have regained its pre-pandemic level. There is also every prospect that this year the U.S. economy will experience its strongest boom in the past forty years.

At the same time that the U.S. economy is roaring back to life, U.S. asset prices seem to be on fire. Over the past year, U.S. stock prices have increased by around 85 percent or by their strongest yearly increase on record. Meanwhile, over the past twelve months, U.S. house prices have increased by 12 percent.

Now while the rapid increase in economic growth and employment, as well as buoyant asset prices, are certainly cause for celebration, it has to raise serious questions about the appropriateness of today’s expansive economic policy setting for the attainment of long-run economic prosperity.

With an already strongly recovering economy and with clear signs of froth in equity and housing markets, does the U.S. economy really need the massive amount of budget and monetary policy stimulus that it is now receiving?

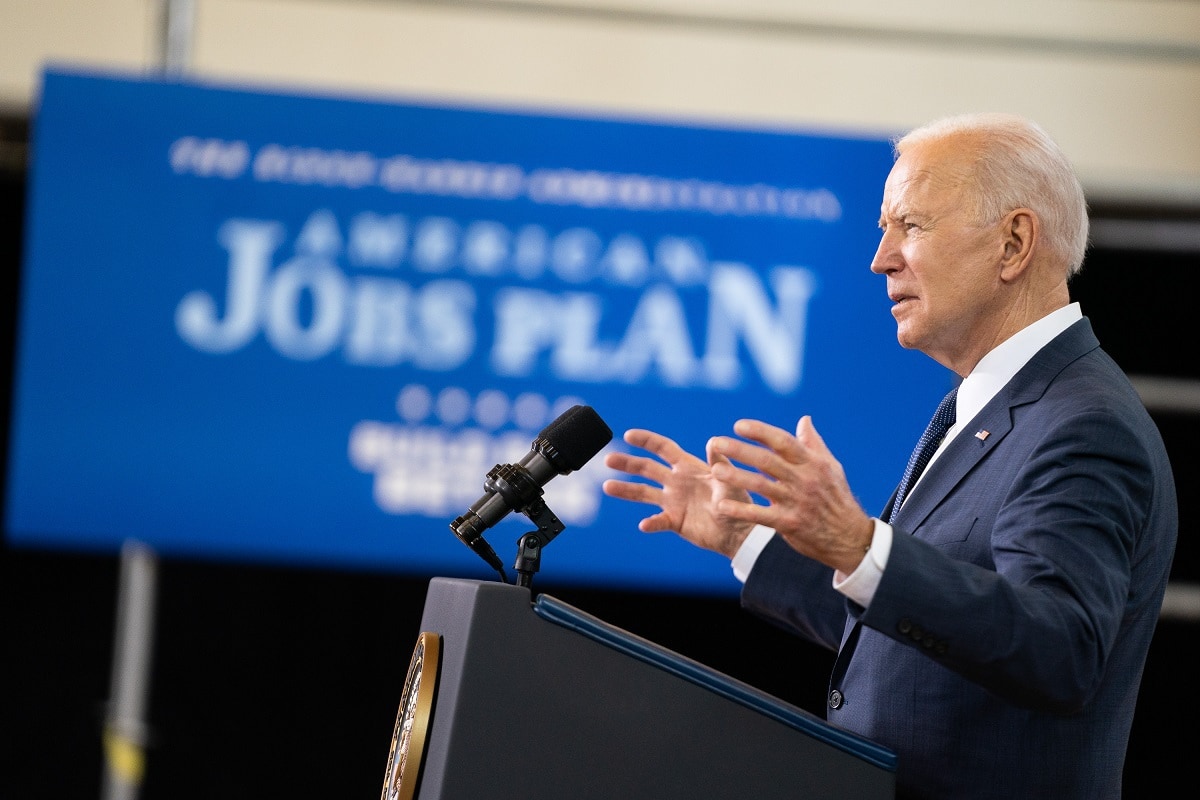

Even on its own, the $1.9 trillion budget stimulus that Joe Biden rushed through Congress this Spring would seem to risk overheating the U.S. economy by the end of the year. Coming on top of a generous bipartisan budget stimulus at the end of last year, the Biden stimulus would imply that the U.S. economy will be receiving a staggering 13 percent of GDP in budget stimulus this year. Such stimulus would seem to be excessively large at a time that the Congressional Budget Office is estimating that US output is currently only some 3 percent below its potential level.

Similarly, it might be asked how much sense does it make for the Federal Reserve to still keep its monetary policy pedal to the metal at this juncture? With the economy strongly recovering and with so much budget stimulus and so much pent-up household demand in the economy, might the Fed not be courting inflation by keeping its interest rate at the zero bound and by continuing to purchase $120 billion in Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities each month? As if to underline that risk, as a result of the Fed’s expansionary policy stance, the U.S. broad money supply is now growing at around 30 percent, or at its fastest pace in the past sixty years.

Yet another reason to question the appropriateness of the Fed’s continued monetary policy largesse are the large bubbles that seem to be forming in both the U.S. stock market and the U.S. housing market. U.S. equity valuations are now at their highest levels since the eve of the 1929 stock market crash, while U.S. housing prices are increasing at their fastest pace since the 2006 housing bubble. Continuing to buy bonds at the current rapid pace that the Fed is now doing carries the real risk of further inflating those bubbles.

Unfortunately, neither the Biden Administration nor the Fed is showing any signs of moderating their expansive policy stance anytime soon. Indeed, the Biden Administration is now pushing an Infrastructure Plan and a Family Plan each with price tags of close to a staggering $2 trillion. Meanwhile, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell keeps insisting that the Fed is “not even thinking about thinking about raising interest rates” until it sees clear signs of inflation.

All of this likely means that the U.S. economy and the U.S. asset markets will keep partying in the months immediately ahead as if there were no tomorrow. However, it also likely means that both the U.S. economy and U.S. asset prices will suffer from a nasty hangover when the party comes to an abrupt end once inflation raises its ugly head.

Desmond Lachman is a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He was formerly a deputy director in the International Monetary Fund’s Policy Development and Review Department and the chief emerging market economic strategist at Salomon Smith Barney.