The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is recommending the federal government and state governments stop administering Johnson & Johnson’s Covid‐19 vaccine. Some 7 million Americans have received the vaccine, whose regimen requires only one dose. The FDA issued the recommendation after reports that six women between the ages of 18 and 48 developed blood clots after taking the vaccine. One of the women is in a hospital in critical condition. Another died. While the FDA’s recommendation is merely advisory, it is likely to halt vaccinations at federal facilities. States including Ohio, New York, and Connecticut have paused their administration of J&J’s vaccine. Critics fear that stopping the use of the vaccine will leave many Americans without protection from the virus and weaken confidence in all Covid‐19 vaccines.

According to the New York Times:

the concerns about Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine mirror concerns about AstraZeneca’s, which European regulators began investigating last month after some recipients developed blood clots.

Out of 34 million people who received the vaccine in Britain, the European Union and three other countries, 222 experienced blood clots that were linked with a low level of platelets. The majority of these cases occurred within the first 14 days following vaccination, mostly in women under 60 years of age.

On April 7, the European Medicines Agency, the main regulatory agency, concluded that the disorder was a very rare side effect of the vaccine. Researchers in Germany and Norway published studies on April 9 suggesting that in very rare cases, the AstraZeneca vaccine caused people to make antibodies that activated their own platelets.

Nevertheless, the regulators argued, the benefit of the vaccine — keeping people from being infected with the coronavirus or keeping those few who get Covid‐19 out of the hospital — vastly outweighed that small risk. Countries in Europe and elsewhere continued to give the vaccine to older people, who face a high risk of severe disease and death from Covid‐19, while restricting it in younger people.

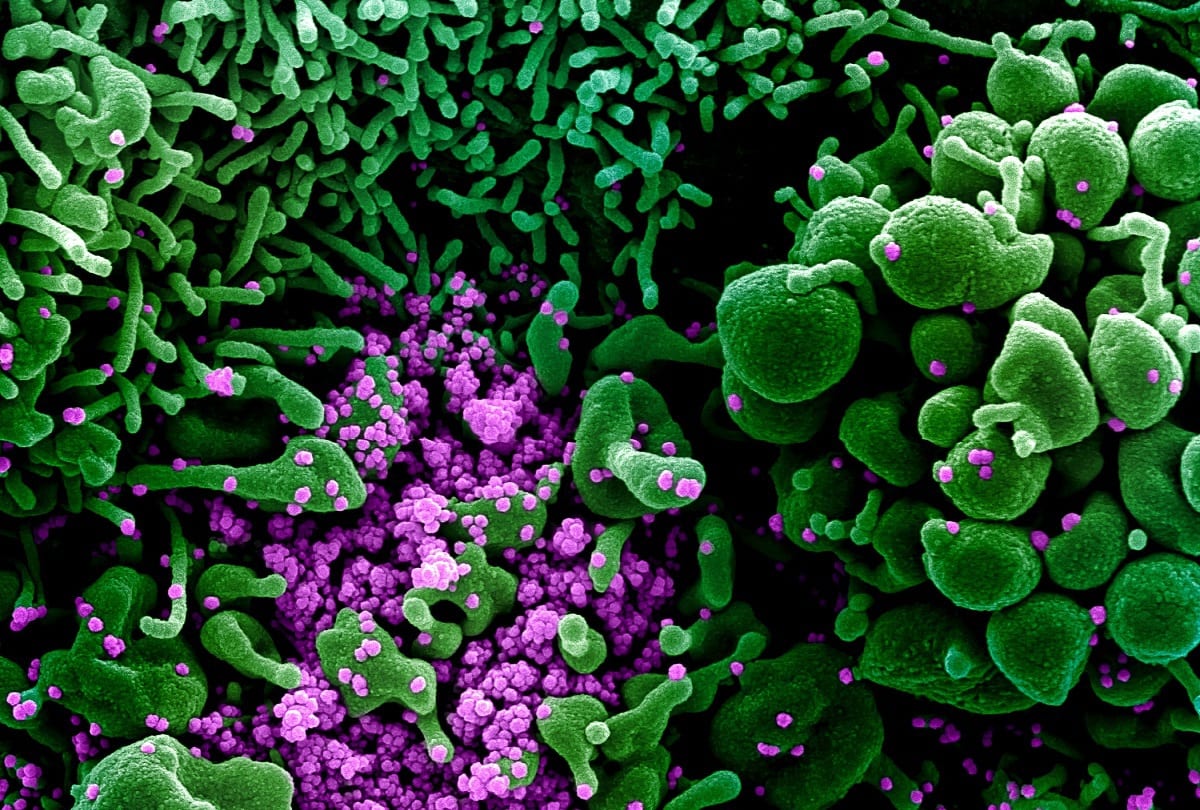

Both AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson use the same platform for their vaccine, a virus known as an adenovirus. On Tuesday, the Australian government announced it would not purchase Johnson & Johnson vaccines. They cited Johnson & Johnson’s use of an adenovirus. But there is no obvious reason adenovirus‐based vaccines in particular would cause rare blood clots associated with low platelet levels.

So what’s the right move? Are the benefits of the J&J vaccine worth the very small (and uncertain) risk of blood clots among some women?

The answer is different for everybody. A 35‐year‐old woman who is at very low risk of getting seriously ill from Covid‐19 but who has reason to fear a blood clot might decide to stay away from the J&J vaccine and wait until she can access the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine. A 65‐year‐old man with comorbidities that make him highly vulnerable to Covid‐19 may decide the benefits of the J&J vaccine vastly outweigh the risk of blood clots.

Leaving such decisions to government, whether federal agencies like the FDA or even state governments, imposes a single answer on all patients, even on patients for whom it’s the wrong answer. It is a good thing that the FDA only recommended that the federal and state governments stop using the J&J vaccine, rather than ban it entirely. A recommendation still allows states, and therefore consumers in those states, to make a different decision. Nevertheless, the FDA and compliant states are blocking untold Americans from accessing an immensely valuable vaccine. This episode thus highlights another downside of having government allocate vaccines and another benefit of leaving such matters to markets. There also remains the risk that the FDA could ban the J&J vaccine just as it is banning the AstraZeneca vaccine.

Defenders of the FDA object that the agency would set back vaccination efforts even more if it ignored what turns out to be a more serious problem. This is, of course, true. The problem is that Congress and the FDA always value lost lives for which they might take the blame more than lost lives for which they will not suffer blame. The late Nobel Prize‐winning economist Milton Friedman explained why the incentives the FDA faces produce perverse outcomes, and why we would be better off without it:

As I write elsewhere, “Several studies have estimated that the FDA would save more lives if it reduced the length of its new drug approval process.” But Congress and the FDA do not reduce the cost of the drug‐approval process because they would only take the blame for what goes wrong; they would not get the credit for what goes right.

Covid‐19 vaccines are the exception that proves this rule. The FDA approved them in less than a year, rather than the 12–15 years it typically takes to approve new drugs. The agency was able to do so because the public was acutely aware of the costs of blocking these items. But the J&J and AstraZeneca vaccines show the FDA has not changed its stripes.

Michael F. Cannon is the Cato Institute’s director of health policy studies. Cannon has been described as “an influential health‐care wonk” (Washington Post), “ObamaCare’s single most relentless antagonist” (New Republic), “ObamaCare’s fiercest critic” (The Week), and “the intellectual father” of King v. Burwell (Modern Healthcare). He has appeared on ABC, BBC, CBS, CNN, CNBC, C-SPAN, Fox News Channel, and NPR. His articles have been featured in the Wall Street Journal; the New York Times; USA Today; the Washington Post; the Los Angeles Times; the New York Post; the Chicago Tribune; the Chicago Sun‐Times; the San Francisco Chronicle; SCOTUSBlog; Huffington Post; Forum for Health Economics and Policy; JAMA Internal Medicine; Health Matrix: Journal of Law‐Medicine; Harvard Health Policy Review; the Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law, and Ethics; and the Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law.