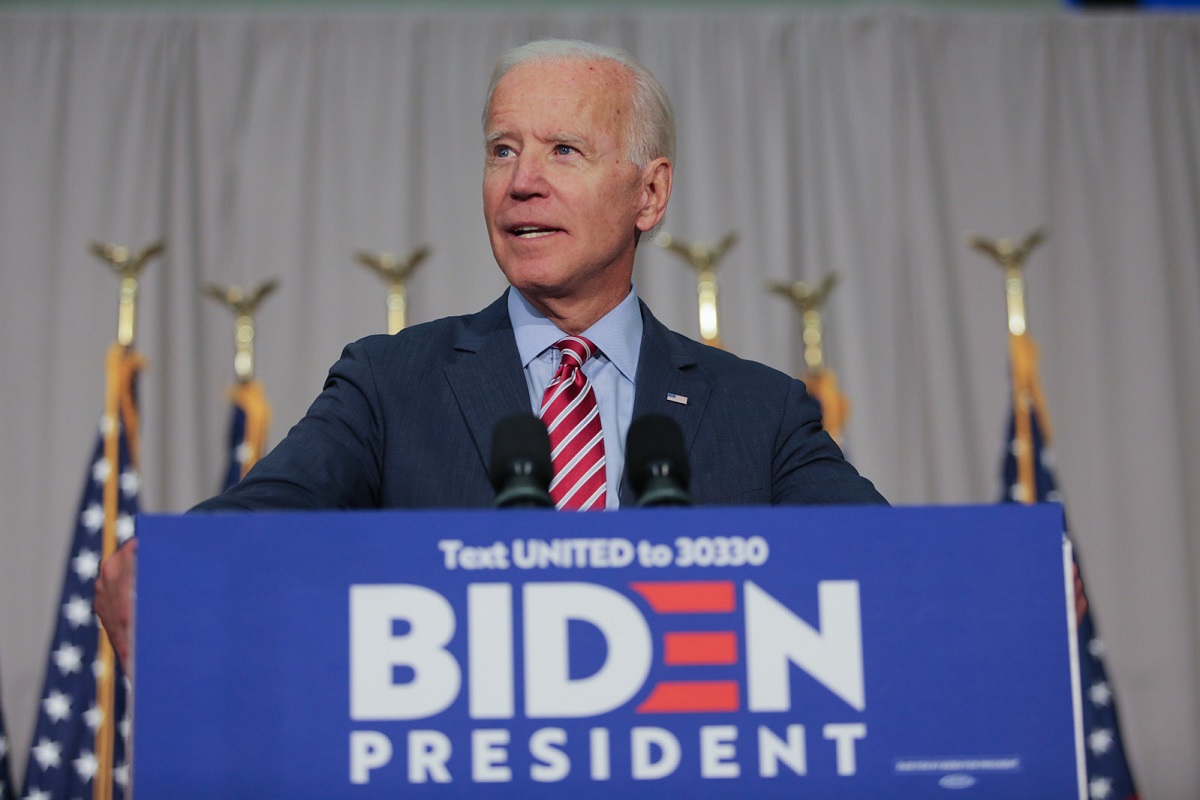

On April 29th, President Joe Biden marked his one-hundredth day in office by proposing multi-trillion-dollar spending plans to complement his multi-trillion infrastructure plan. The plans come on the heels of the multi-trillion dollar stimulus package that he signed during his first month in office. Political observers immediately praised the Administration for its bold program and suggested the president was poised for success.

Tucked in the speech, however, the president unknowingly conceded his program would fail.

Early in the speech, Biden stated the economy had created more than 1,300,000 new jobs in those first 100 days. Later, however, Biden noted that twenty million Americans were out of work.

A quick back-of-the-envelope math shows that it will take approximately four years for employment to return just to pre-pandemic levels.

Biden’s failure to deliver a robust economic recovery does not preordain a single term. Subpar economic growth does not imperil all presidencies. See Bush 43 in 2004 and Obama in 2012.

Not all one-term presidencies foreshadow crises. After four gloomy years (Carter, Bush 41), voters can and do find salvation in sunnier alternatives (Reagan, Clinton).

Nevertheless, the 2020s will be turbulent — it will be the storm before the calm.

Why?

Because the two major historical cycles that propel American history will converge and overwhelm any president, much less Joe Biden.

Every eighty years, the institutions comprising the American federal republic re-balance.

Between the Revolutionary War and the Civil War, the federal government was minimalist. The “States of America” were sovereign before the war and committed to retaining it after the war. Throughout the period, the states conceded little authority to the federal government, notably in regard to slavery, and often threatened to nullify its legislation when it conflicted with their interests.

After the states went to war over slavery eight decades later, the victorious states amended the Constitution to re-balance in favor of the federal government. This arrangement held for another eighty years until the end of the Great Depression and World War II and the onset of the Cold War. Emerging a superpower tasked with the leading the free world back to prosperity and against communism, the federal government established a national security apparatus unprecedented in the country’s history and undertook an expanded role in the economy.

Simultaneously, every fifty years, the American economy’s dynamism will enrich and impoverish different segments of the public, provoking a heated political debate over the nation’s future. As the prevailing economic consensus is undermined, a new political coalition will emerge and win the presidency, establishing a new consensus and restarting the fifty-year clock.

George Washington’s election to the presidency established the dominance of the mercantile and financial class over the country’s agricultural interests. Then rural discontent led to Andrew Jackson’s election and for the next fifty years, the agricultural sector would dominate before slowly ceding ground to the burgeoning industrial economy.

By the 1880s, a succession of pro-business presidents marked the increasing dominance of industry (“the robber barons”) who defeated agricultural interests permanently by electing William McKinley in 1896.

As America became a world industrial power, workers became increasingly dissatisfied with their share of the nation’s wealth. After the Crash of 1929, labor became the basis for a powerful new coalition that rallied to Franklin Roosevelt in 1932.

Roosevelt’s presidency would inaugurate government intervention in the economy, higher taxes on the wealthy, and social insurance programs to alleviate poverty.

Government intervention in the economy held until the toll of high taxes and government regulation became evident in the dearth of entrepreneurship and investment needed to keep the economy competitive.

In 1980, the middle class would turn to a candidate promising lower taxes, smaller government, and free trade — Ronald Reagan. Reaganomics – tax cuts and deregulation — spurred the economy’s transition from industry to information and increased integration into global trade.

Even in the highly unlikely event that employment returns to pre-pandemic levels before Biden seeks re-election, Biden will be presiding over institutions that are terminal and an economy that is essentially moribund.

The federal government has metastasized, encompassing a sprawling amalgamation of agencies, each with their own priorities (even if they conflict), regulatory authorities (without being accountability for outcomes), and budget requirements (which never decrease).

And big government has its own constituency. The federal workforce became a class unto their own. Well educated, secure in highly compensated jobs, and socialized in the Maryland and Virginia suburbs of D.C., they have been sustained by historic spending since 9/11, virtually immune to the economic destruction across the country. Worse, it has been cruelly disdainful of the very public it serves. In designing a takeover of the country’s health care system, one decision-maker revealed “Lack of transparency is a huge political advantage, and … the stupidity of the American voter … [was] critical to getting the thing to pass.”

The national security establishment failed to prevent 9/11 and attempted to nation-build in the world’s most dysfunctional regions and paid for it by borrowing trillions from China, which is now using the billions in interest payments to fund its own massive military modernization and trans-Eurasian initiatives.

The low tax, small government approach succeeded in revitalizing the economy but free trade introduced divergent trends. Consumers benefitted from lower prices but the nation’s industrial base slowly hollowed out and millions of blue-collar workers lost their jobs as corporations relocated overseas to capitalize on lower labor costs.

After the dotcom bust and 9/11, Wall Street eschewed investing once again in America and instead scrambled to find yield anywhere it could, including the normally placid housing market.

The result was an overheated housing sector that would crash in 2008, expelling millions from their homes and a multi-billion bailout for major financial firms paid for by American taxpayers.

Now, America is amidst a New Great Depression and the full devastation wrought by the ill-conceived lockdown will require years to recover.

Between March and September 2020, more than sixty million people lost their jobs – thirty years of job growth disappeared in six months. The many months spent unemployed and quarantined eroded professional skills and networks. Moreover, the pain fell unevenly. The “asphalt class”– small businesses and blue collar workers – suffered, not the “ethernet class” – the white collar professionals who simply began working from home via Zoom.

Biden is not the president for these times.

Biden has been in government at the federal level since 1973 and he has never questioned its scope and scale. Indeed, presiding over a more stridently progressive party, Biden has proposed even greater government authority over American’s lives – Swedenesque tax rates and green Soviet-style Five Year Plans.

Arguably, Biden is the product and conservator of these decaying institutions.

Furthermore, Biden bitterly clings to the obsolete Roosevelt economic consensus – more government intervention, higher taxes, and wealth redistribution.

The cumulative challenges of the 2020s will be resolved in the form of a president who constructs “simple government” – an approach that rationalizes government’s scope and scale, undoes its default to military intervention, and reverses government interference in the economy.

Scores of wonky proposals to simplify government abound – consolidating the bureaucracy, modernizing financial systems, and evaluating outcomes instead of outputs. The Government Accountability Office — has published reports listing recommendations for high-risk areas as well as the abundance of governmental duplication, overlap, and fragmentation. (Even budget reductions alone — genuine reductions, not just reductions in the rate of growth — would be welcome.)

In this regard, the COVID restrictions had one silver lining – changes to education. As noted above, the pain experienced was uneven. Parts of the public could capitalize on quality remote education or less restrictive attendance policies. In other places, families had unreliable Internet connections or faced unionized teachers refusing to re-open schools. Parents responded by home schooling, enrolling in private schools, or creating “micro-schools,” small classes led by under-employed teachers.

If the information economy has demanded one thing, it is educated workers. If the asphalt class has demanded one thing, it is opportunity and social mobility.

Biden will indeed be a “transitional figure,” how long the storm lasts before the calm will be an open question.