President Joe Biden’s bold budget proposals must raise serious questions about the country’s economic future. Not only do they raise immediate inflationary concerns. They also raise concerns about the country’s long-run debt sustainability.

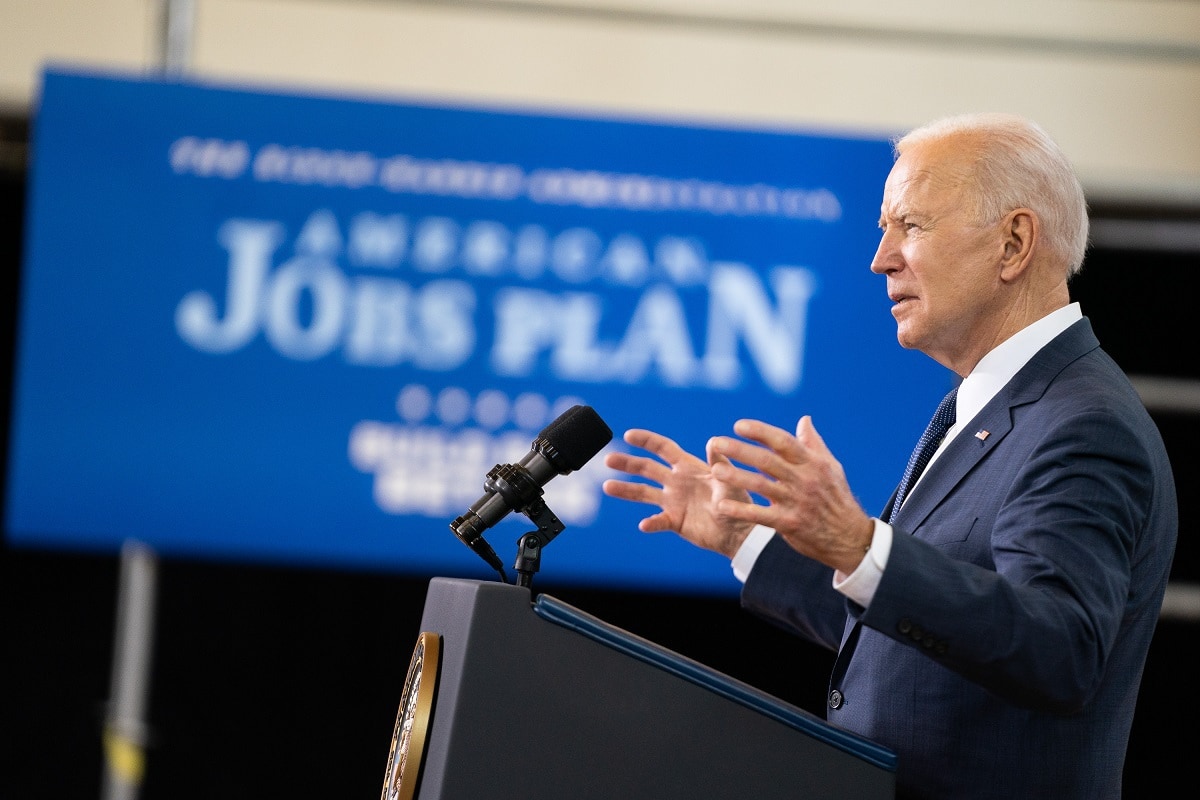

In his first 100 days in office, Mr. Biden has come up with three very large budget proposals at an estimated total cost of a staggering $6 trillion or close to 30 percent of GDP. First, he rushed through Congress a $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan stimulus package. Now he is proposing an American Jobs Plan aimed at improving the country’s infrastructure and an American Families Plan to address social issues each with price tags of close to $ 2 trillion.

The inflationary consequences of the American Rescue stimulus package can be gauged by comparing it to the estimated degree to which US output currently falls short of the level that it could potentially reach at full employment. The American Rescue stimulus, together with the December 2020 bipartisan stimulus package, would imply that this year the economy will receive around 13 percent of GDP in budget stimulus. Yet according to the bipartisan Congressional Budget Office, the country’s so called output gap is only 3 percent.

The American Rescue stimulus must be considered all the more inflationary when one takes into account the context in which it is occurring. It is taking place at a time that the economy is already recovering strongly, monetary policy remains extraordinarily accommodative, and a great degree of pent-up demand has been built up in the economy during the lockdown that must now be expected to be released as the economy returns to normal. It is also occurring at a time that the broad money supply is growing by 30 percent or at by far its fastest pace in the past sixty years.

The shaky way in which Mr. Biden is planning to finance his American Jobs Plan and his American Families Plan would further add to long-run inflationary pressure.

Whereas the Jobs Plan envisages close to a $2 trillion increase in public spending over the next eight years, it only envisages collecting the revenues to finance that expenditure over a fifteen-year period. This implies that over the next decade the Jobs Plan would add an estimated $1 trillion to the country’s public debt.

The way in which Mr. Biden plans to finance his Families Plan could also add to long-run inflationary pressure. While Mr. Biden proposes to finance this plan through tax increases, he has made clear that this will not involve any tax increase on those earning less than $400,000 a year. He has also argued that taxing the wealthy will not change their spending habits. Yet if taxing the wealthy does not change their spending habits, it means that there also will not be any offset to the increase in aggregate demand associated with the increased public spending on his Families Plan.

Beyond adding to immediate inflationary pressure, Mr. Biden’s budget proposals will complicate the Federal Reserve’s task of keeping inflation in check over the longer run. It will do so by substantially increasing the size of the public debt. Even before Mr. Biden’s budget proposals, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that the US public debt would rise to almost 110 percent of GDP by 2030 or to a higher level than prevailed immediately after the Second World War. After Mr. Biden’s budget proposals, the public debt will rise to even more troubling levels.

As the public debt rises, the Fed’s ability to fight inflation would become increasingly constrained. With a high public debt level, the Fed will be under tremendous political pressure not to raise interest rates to fight inflation since higher interest rates would increase the government’s debt servicing costs and limit the room for other government expenditures.

One has to hope that the Biden Administration will soon adopt sounder policies to finance its ambitious public spending programs than he has been proposing to date. If not, we should resign ourselves to having to live with higher inflation for many years to come.

Desmond Lachman is a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He was formerly a deputy director in the International Monetary Fund’s Policy Development and Review Department and the chief emerging market economic strategist at Salomon Smith Barney