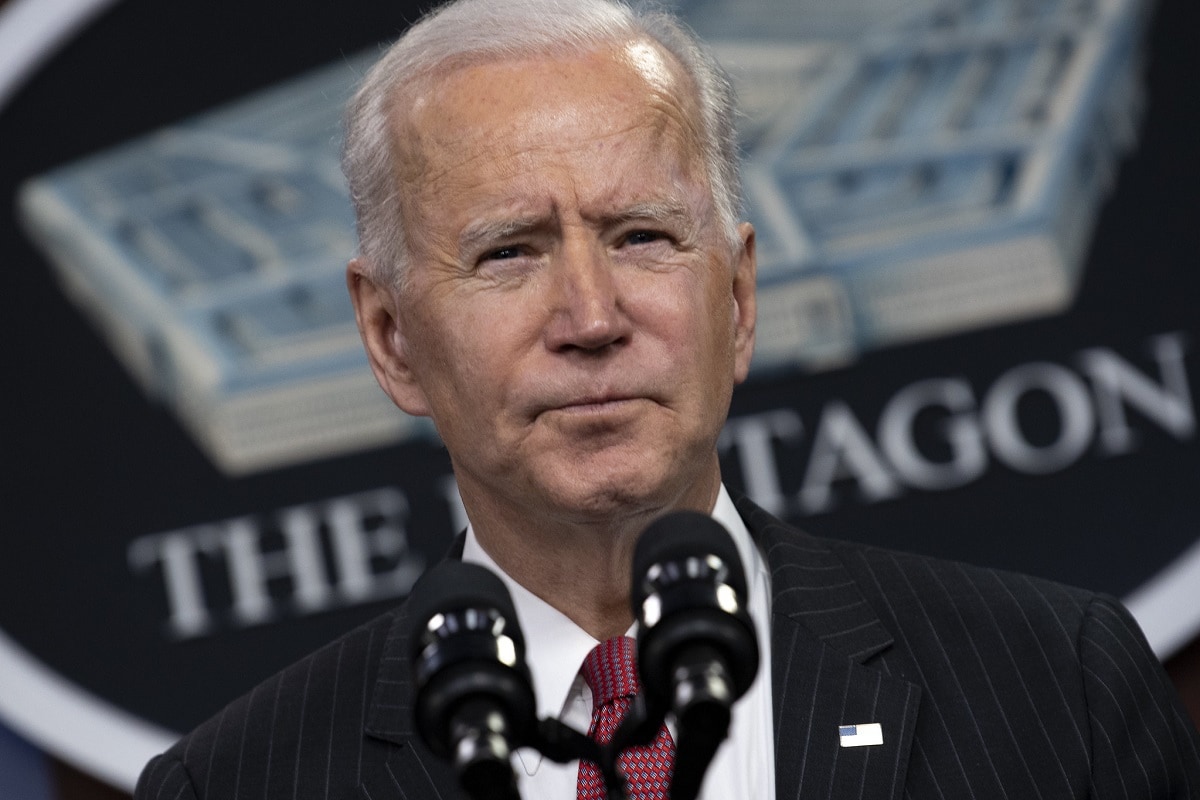

As President Joe Biden met with Russian President Vladimir Putin in mid-June about the spate of Russian-origin cyber-attacks on America, a growing number of security analysts joined in repeating the refrain: “Hit them back!”

But what if the threat of a cyber counterattack isn’t a realistic method of deterrence?

As the character Dr. Strangelove said in the eponymous movie, “Deterrence is the art of producing in the mind of the enemy the fear to attack.” For many, deterrence is like an old friend from the last Cold War, grudgingly admired for preventing nuclear war. Having a like-for-like response in a match between two powers means that each fighter knows he will be hit as hard as he punches or harder, and that victory will be pyrrhic or elusive, and because of that he will be less likely to start a fight. That is, he is deterred, and his deterrence means the safety of his sparring partner.

Extending this logic to cyberspace has adherents. Mr. Biden’s national security advisor, Jake Sullivan, warned that Moscow would face “seen and unseen” consequences to a recent cyber-attack, which many analysts took to mean digital retaliation in addition to sanctions.

On the other side of the political spectrum, retired general Jack Keane also encouraged U.S. Cyber Command to retaliate: “They should attack the cyber-infrastructure of these criminal organizations, shut them down temporarily, but if we continue to persist in doing it, it’ll eventually become a deterrence because every time they pull the trigger, we shut them down and that will have an impact on them…”

Deterrence, however, might not be the friend we need for the world we live in today. Understanding how Russian cyber-attackers work is important to understanding why deterrence doesn’t work. Right now, criminal enterprises operate as normal businesses in Russia as long as they don’t attack Russia or its economic interests. There’s even reverse-engineered code on malware showing that the malicious software of Russian origin shuts down if it detects a Cyrillic keyboard layout or input scheme—an easy way to protect most Russian systems from their compatriots’ own malware.

Despite this tolerance, the problem that presents itself is that these are not state actors doing the bidding of the government, so we cannot respond to them like they are. The individual hackers are hard enough to identify, much less successfully target with effect, and while these malware operations benefit from authorities looking the other way at their conduct, striking back at that government is not clear deterrence to the attackers.

This leads the question: what does deterrence do to such an adversary? The United States, as a nation ruled by laws, lacks brazen criminal enterprises that could create a symmetric impact in Russia if unleashed. That leaves only our military and intelligence cyber capabilities, which must operate within the laws of war. Since it’s impossible to wage war on a private organization—even one operating with tacit Russian approval— how do we strike back when another hospital suffers a shutdown due to Russian ransomware? Do we, using our state cyber capabilities, attack civilian targets, or hope that an attack on the Russian government turns up the heat on these criminal organizations?

Both of these options are awful. Either we’re doing the cyber-equivalent of bombing hospitals in retaliation, or we’re committing acts that can easily and rapidly escalate into war. It is clear that turning loose state capabilities to “hit them back” only guarantees that we’ll be hit even harder in the next round. Now, we are deterred. Our good offensive strategy has become our worst defense because it’s not stopping the attacks, and it might even be making them worse for the businesses that get hit next.

We need a solid defensive line. After the Colonial Pipeline was shut down due to a ransomware attack, the company promised to hire a Chief Information Security Officer and increase its cybersecurity spending. Better late than never, but the implication of this announcement was that the company had no significant security leadership and was underfunding its security practice. It’s all too common a story. The same organizations that will spend money on locks, security guards, fences and gates balk at spending on cybersecurity until it is too late.

It’s time for that to change. The Biden administration’s executive order on cybersecurity issued in May is a good start, but only a start. Both by providing resources and mandating requirements, the government should guide and incentivize public companies and other organizations that provide essential services to take the same basic security steps that are now required of government agencies. Organizations which fail to take basic steps should face legal liability for damages. And software should be graded by industry groups for safety.

Sometimes your best defense is a good offense. In this case, our best defense is, in fact, the best defense.

Matt Erickson is the Vice President Solutions of SpiderOak, a secure communications data, and aerospace company.