What does the AUKUS deal mean for nuclear proliferation? The answer depends on how the deal plays out for Australia, and on the risk tolerance of other major navies.

With respect to nuclear weapons, concerns over proliferation are understandable but manageable. Australia can be safely excluded from nuclear fuel cycle issues and in any case, has been a reliably good nuclear citizen. The larger proliferation issue involves the decisions that other states across the Asia Pacific (and indeed, around the world) about the future of their submarine fleets.

There are certainly contexts in which diesel-electric submarines are preferable to their larger nuclear cousins. Conventional submarines are generally cheaper and can operate more quietly than SSNs. They do not require intense human capital development in order to manage reactors, handle nuclear material, and prevent accidents. However, the Pacific Ocean is large, and nuclear submarines have obvious advantages in such an environment.

The nuclear question seems to have made France quite upset. Reportedly France offered Australia the opportunity to convert to nuclear submarines, but Australia had already soured on the prospects for a deal. Australia also came to the understandable conclusion that the United States represented a more responsible long-term partner than France. And perhaps the biggest problem for France is that its boats are simply not well-regarded in the submarine community.

But several other countries around the world now have difficult decisions to make about their submarine fleets. Brazil is already constructing a nuclear attack submarine with French assistance, a decision that may have influenced Australian thinking. South Korea, Japan, and Canada all have difficult decision to make about the future of their submarine programs. A.B. Abrams has made the case that South Korea and Japan have different strategic needs than Australia, and consequently do not require SSNs. But while South Korea and Japan are in less demanding “tyranny of distance” situations than Australia, it is not at all difficult to imagine scenarios in which either could benefit from the long-range presence that only an SSN can offer.

Canada is an interesting case. With access to three oceans, Canada could certainly use the range offered by nuclear boats. Canada contemplated nuclear submarines in the 1950s, but eventually opted for conventional boats. In the 1980s Canada once again considered the acquisition of SSNs, with partnerships with either France or the United Kingdom on the table. Indeed, the United States reacted with hostility to the Canadian proposal in the 1980s, in part because of concerns about deconfliction in the Arctic and in part because of the potential for French or British participation. However, Canadian political culture remains more pacific than Australian, likely making the acquisition of nuclear technology a tougher sell. On the other hand, Canada is still in a dispute with China over the imprisonment of its citizens, which could make the Canadian public more receptive to a plan that would enable Canadian ships to operate with Australian and American units in the Western Pacific. Moreover, given US support for Australian SSNs, it would be very difficult for the US to offer any opposition to a similar deal for the Canadians.

Of course, much can still go terribly wrong. Australia’s Collins-class submarines have not been regarded as a success, and while most of the fault with the French submarine deal lies with France, some also belong to Australia. Construction of components of the subs in Australia could still go wildly over-budget in ways that make it impossible for Australia to continue. A new Australian government, facing pressure from China, might back away from the deal with catastrophic diplomatic repercussions. If any of these things happen, the attraction of nuclear submarines for non-nuclear powers will undoubtedly diminish. If the deal goes well, however, it opens the prospect for the Royal Australian Navy to become a major player in the Western Pacific. This is something that each of Seoul, Tokyo, and Ottawa will watch carefully.

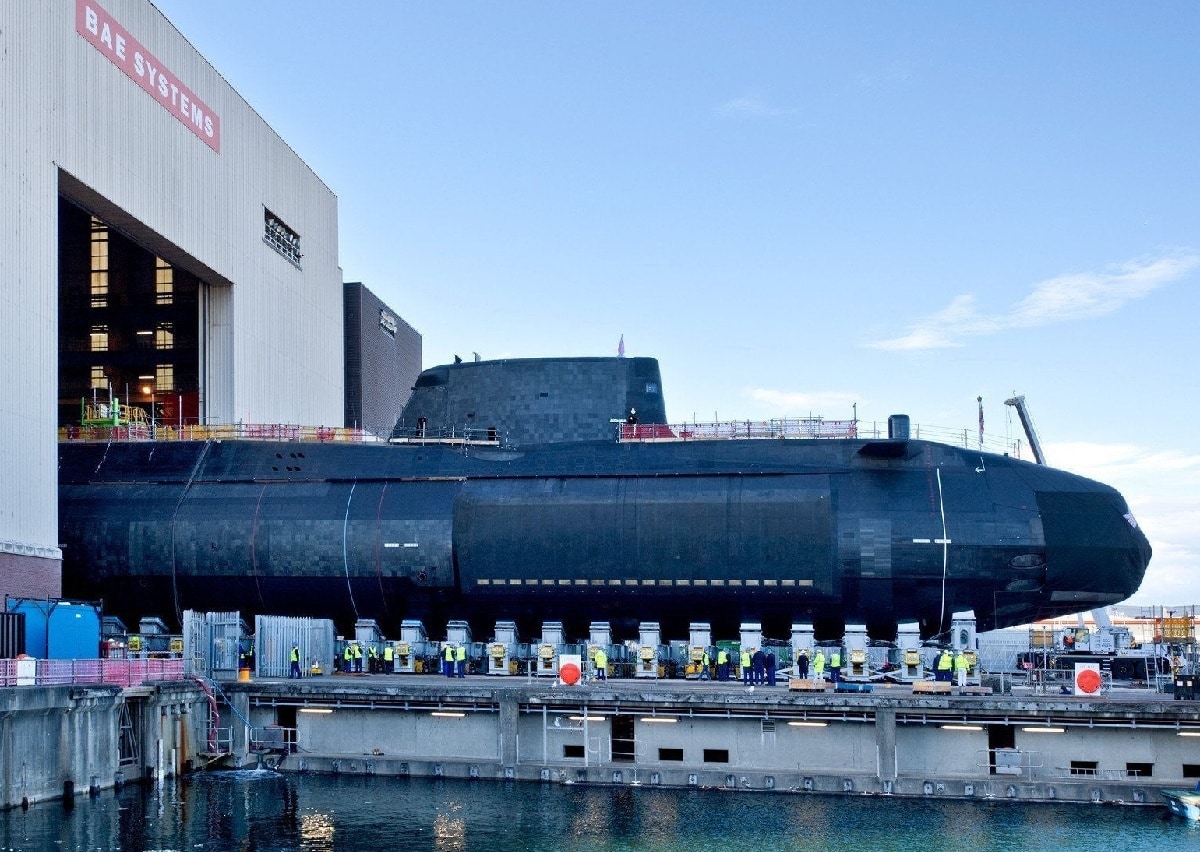

US Navy Seawolf-class submarine. Image: Creative Commons.

Now a 1945 Contributing Editor, Dr. Robert Farley is a Senior Lecturer at the Patterson School at the University of Kentucky. Dr. Farley is the author of Grounded: The Case for Abolishing the United States Air Force (University Press of Kentucky, 2014), the Battleship Book (Wildside, 2016), and Patents for Power: Intellectual Property Law and the Diffusion of Military Technology (University of Chicago, 2020).