Huzzah!

The news broke this week that Australia, Great Britain, and the United States have forged a new alliance dubbed AUKUS, for Australia-U.K.-U.S. Among other things, the alliance will help the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) construct a contingent of at least eight nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSNs) by the late 2030s. While allied leaders named no names, the SSN initiative is meant to help counter a certain large, domineering Asian country that operates the world’s most numerous navy.

Nuclear-powered boats make perfect sense for Australia, which occupies strategic real estate just outside the South China Sea rim, a.k.a. the southerly arc of Asia’s first island chain. A competitor has to be in embattled waters more or less constantly to compete there with any hope of success. But like all Pacific nations, Australia confronts the tyranny of distance. The RAN’s current flotilla of Collins-class diesel-electric subs (SSKs) can put in an appearance in the South China Sea but can’t stay on their patrol grounds for long before returning home for fuel and stores.

By contrast, an SSN’s on-station time is limited only by its capacity to store food and stores sufficient to supply the crew’s needs. Some years ago, in fact, a team from the Washington-based Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments estimated that an SSN operating from Australian harbors could make a 77-day patrol in the South China Sea; an SSK could manage just 11 days. With just six Collins-class boats in the inventory, the RAN would find it hard to rotate boats out on patrol swiftly enough so that one was always on scene. The pace would run submariners ragged.

Nukes change that. For comparison’s sake, 77 days is comparable to how long U.S. Navy nuclear-powered ballistic-missile submarines spend on patrol. That’s a significant stretch of time. In short, naval nuclear propulsion confers staying power in distant expanses, and thus bolsters the allies’ capacity to deter conflict or to fight and win if forced to it. AUKUS portends well for the great-power strategic competition in the Pacific.

But the hoopla about Aussie SSNs obscured a bit of news that could be more consequential—in a good way—in the near term. The Australian Financial Review reports (hat tip: Joseph Trevithick, The Drive) that the U.S. Navy may start operating Virginia-class SSNs from HMAS Stirling, the RAN base in Perth. This would provide the allies an interim nuclear-submarine capability along that South China Sea rim, and it would do so years before RAN SSNs take to the sea.

Sooner is better. After all, senior leaders have come to believe a certain overbearing Asian country may act against Taiwan in the next few years. The same might hold true for South China Sea or East China Sea hotspots.

Basing American forces in Australia is an idea I’ve been pushing, on my own and with coauthor Toshi Yoshihara, for over a decade now. Think about the advantages such a scheme would bestow. One, geography. The U.S. military presence is rather sparse along the first island chain south of Okinawa. Relations with the Philippines have been tenuous during the Rodrigo Duterte presidency. While Manila opted not to cancel the visiting-forces agreement that permits U.S. forces on Philippine soil (or abrogate the U.S.-Philippine mutual defense treaty, as Duterte threatened to), it also seems doubtful that the archipelago will resume being the major military hub it once was.

It’s hard to compete in the South China Sea or Taiwan Strait without forces based nearby.

Australia furnishes a partial substitute for Philippine bases—a superior one in some respects. It occupies a geographic position at the seam between the Pacific and Indian oceans. Naval forces based there can swing between the oceans as circumstances warrant. Now, Perth lies along the country’s Indian Ocean coast, meaning Western Pacific operations will be more cumbersome for SSNs than they would be were boats based in a more centrally located seaport. Still, Perth permits ready access to straits that act as gateways to the South China Sea—Malacca, Lombok, and Sunda—as well as to the South China Sea itself.

HMAS Stirling’s strategic position represents an improvement on Guam, or even Japan, for staging operations in Southeast Asia.

It’s worth noting that AUKUS gives the allied posture in the Indo-Pacific a different look on the map. At present U.S. forces are based at the extreme ends of the Indo-Pacific, chiefly in Japan and Guam to the east and Bahrain to the west. In other words, this is a horizontal, predominantly east-west stance. Assuming Canberra does consent to host Virginia-class subs, the alliance will take on a more vertical, north-south character. Basing in Australia will also complete, round out, and firm up the midsection of the allied defense perimeter that traces along the first island chain.

The arrangement will resemble a distended ellipse enclosing East Asia.

And two, operations. Proliferating bases in the Western Pacific conforms to U.S. Navy operational concepts such as “distributed maritime operations” and to U.S. Marine concepts such as “littoral operations in a contested environment.” Sea-service chieftains envision breaking the fleet down into a force made up of swarms of cheap, small warships and warplanes and using that force in concert with geography to make things tough on an antagonist.

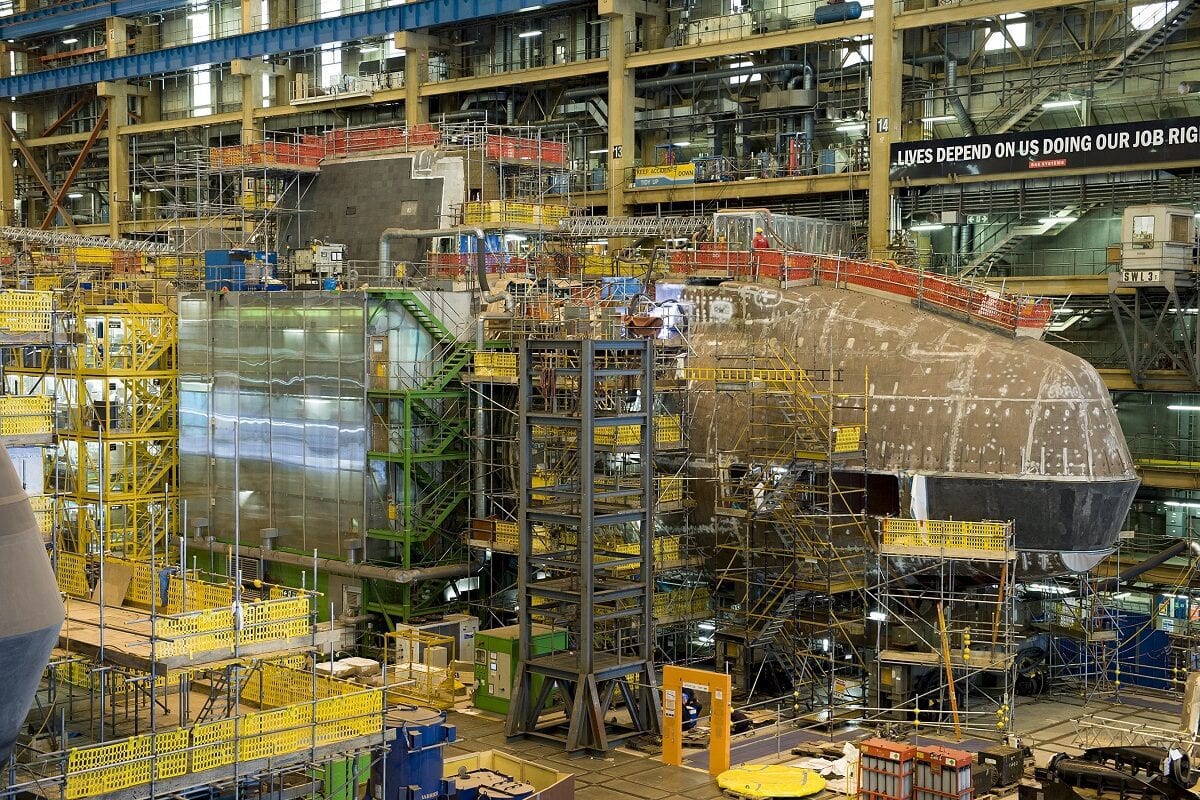

British nuclear-powered Astute-class submarine Audacious under construction at Barrow in Furness shipyard in Cumbria.

Audacious is the fourth of the seven Astute Class submarines being built for the Royal Navy.

The first two boats, HMS Astute and Ambush, are currently undergoing sea trials. The third boat, Artful, is reaching the final stages of her construction at Barrow shipyard. All three are to be based at Faslane on the Clyde.

The more naval stations able to support a distributed force, the better.

There are immediate practical benefits to collocating submarine forces. As the RAN submarine force starts to take shape, and as U.S. SSNs start to make Perth their home, the AUKUS navies ought to fuse allied subs into a multinational fleet to the maximum extent possible. In so doing they can help Australian crews learn how to use atomic propulsion and acquaint them with British and American practices for undersea warfare.

040825-N-5268S-002

Portsmouth, Va. (Aug. 25, 2004) – The nationÕs newest and most advanced nuclear-powered attack submarine PCU Virginia (SSN 774) passes the skyline of Portsmouth, Va., on its the way to Norfolk Naval Shipyard upon completion of Bravo sea trials. Virginia is the NavyÕs only major combatant ready to join the fleet that was designed with the post-Cold War security environment in mind and embodies the war fighting and operational capabilities required to dominate the littorals while maintaining undersea dominance in the open ocean. U.S. Navy photo by Journalist 2nd Class Christina M. Shaw (RELEASED)

Heck, naval leaders ought to think about forming AUKUS crews, regardless of which flag flies over the boat. That would show hostile powers that the allies have skin in the game of their common cause, namely preserving freedom of the sea and fending off great-power predators. That’s the genius of the U.S. Marine F-35 deployment aboard HMS Queen Elizabeth, the Royal Navy aircraft carrier currently plying Western Pacific seas: pick a fight with the British flattop and you’ve automatically picked a fight with America as well.

The concept of skin in the game can dive beneath the waves. And it should. Small tactical and administrative moves such as merging crews can carry major political benefits—benefits such as proving an alliance is indivisible.

So, all hail the incipient Royal Australian Navy SSN program—but let’s commence operating as a team immediately. Time is short.

Now a 1945 Contributing Editor, James Holmes is J. C. Wylie Chair of Maritime Strategy at the Naval War College and a Nonresident Fellow at the Brute Krulak Center for Innovation & Future Warfare, U.S. Marine Corps University. The views voiced here are his alone.