Today, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has one of the world’s largest militaries on Earth. Its People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is now the largest naval force in the world, and it currently operates two aircraft carriers and is building a third. While much of its fleet is made up of smaller warships including frigates, the PLAN operates a number of larger surface combatants including destroyers.

In fact, its Type 055 stealth-guided missile destroyer (NATO designation: Renhai-class) features multi-mission capabilities, as well as flag facilities, are classified as cruisers by the United States.

However, the Chinese PLAN has no plans to build a battleship – and since winning the Chinese Civil War and taking control of the entire mainland in 1949, there has never been a Chinese battleship. Perhaps one factor is that the large capital warships are largely considered antiquated today; whereas smaller and more capable multi-mission warships can do the job of the old behemoth battle wagons.

Another reason could be the Chinese battleships employed during the Qing dynasty at the end of the 19th century didn’t perform all that well during the First Sino-Japanese War (July 1894-April 1895). The war went badly and resulted in a humiliating defeat for China, which resulted in the loss of Taiwan, Penghu and Liadong Peninsula to Japan – while Korea was removed from Chinese suzerainty and transferred to the Japanese sphere of influence.

German Battleships for China

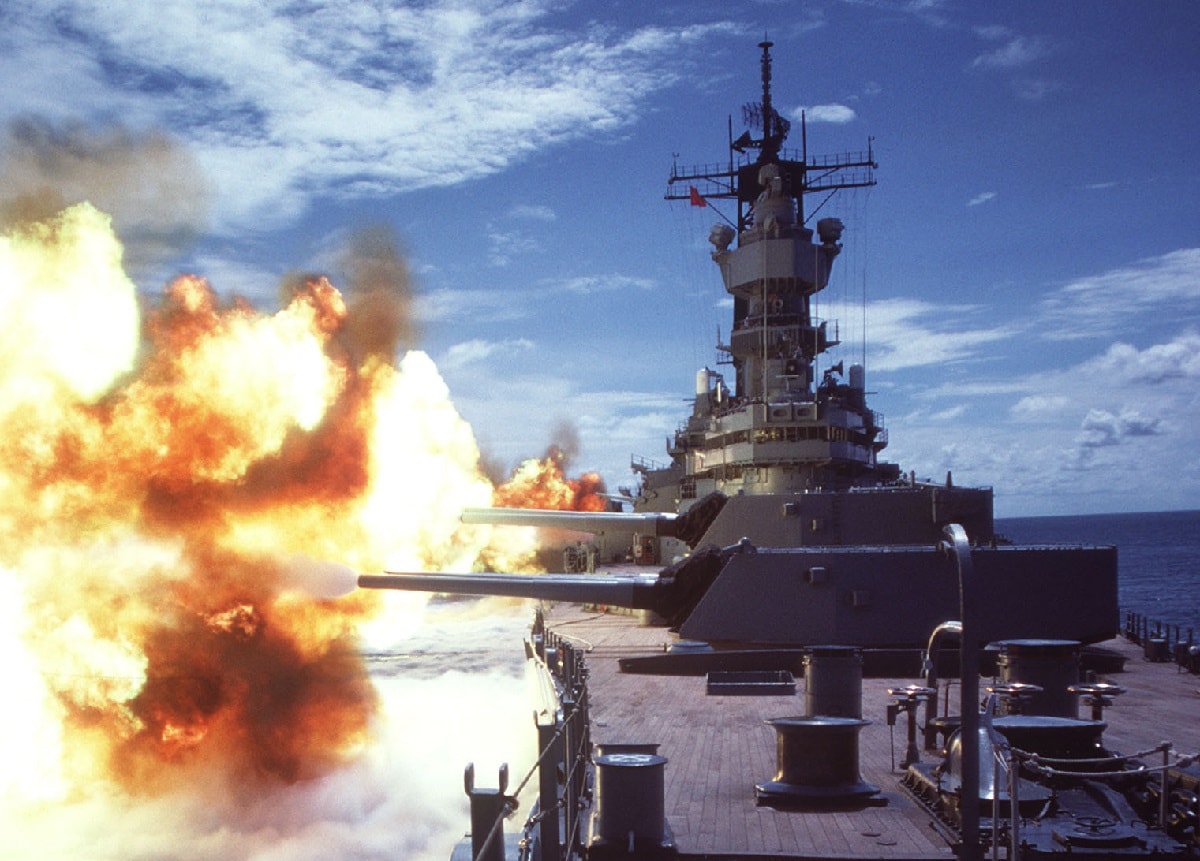

Before the war, the Chinese government purchased two German-made ironclad battleships – Dingyuan and her sister ship Zhenyuan. Both were built in Germany in the early 1880s and each was armed with a main battery of four 12-inch (305mm) guns in a pair of turrets.

These were seen as the most powerful wars in the East Asian waters at the time, they proved ineffective against the Japanese fleet at the Battle of the Yalu River on September 17, 1894. It was the largest naval engagement of the war, and took place just a day after the Japanese victory on land at the Battle of Pyongyang. It was considered to be one of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s greatest victories.

Numbers wise, the Qing forces had the advantage with two battleships, a coastal battleship/fortress, and eight cruisers including two armored cruisers. The Japanese had eight cruisers, including seven protected cruisers. However, the Chinese advantage was lost due to poor leadership and a failure to follow orders in the Qing Navy – that included opening fire while the Japanese fleet was out of range. By contrast, the Japanese held their fire, closed on their enemy and only then opened fire to engage and battered the Chinese fleet. While the Chinese battleships resisted the heaviest bombardment, their crews had been decimated by the Japanese guns.

The situation was made worse when Dingyuan‘s foremast was destroyed, which made it impossible for the flagship to signal the rest of the Chinese fleet. By the time the battle was over, the Chinese losses totaled 1,350 sailors killed or wounded, while four of its cruisers were sunk and another scuttled. Japanese losses were six warships, including an aging ironclad, and losses of 380 killed or wounded.

After the battle, both the flagship Dingyuan and Zhenyuan were repaired and used in the defense of the Weihaiwei from January 20 to February 12, 1895. The battle proved to be another decisive Japanese victory. Before the end of the final Japanese victory, the order was made to scuttle both battleships – a decision that caused many of the senior officers of the Qing’s Beiyang Fleet to commit suicide, including the flagship’s commander, Captain Liu Buchan. A large mine was reported to have been used to destroy the Dingyuan, while the Zhenyuan had been run around and was found by the Japanese to be salvageable. She was seized as a war prize, repaired and commissioned into the Japanese fleet.

Refloated and renamed Chin Yen, she took part in the Boxer Rebellion in China and took part in actions with the Eight-Nation Alliance during the Battle of Tientsin. The warship remained in service with the Imperial Japanese Navy and saw action at the Battle of Tsushima during the Russo-Japanese War in 1905. She was finally decommissioned in 1911, and used as a target ship before being sold for scrap in 1912. Her anchors had been preserved in Tokyo as a monument to Japan’s victory in the Sino-Japanese War, and those anchors were returned to China after the Second World War. Today they are in the Military Museum of the Chinese People’s Revolution in Beijing.

In 2003, the Chinese government began the construction of a full-scale replica of Dingyuan at Weihai. It is now open as a museum ship. In September 2019, the wreck of the original ship was located and some 150 artifacts were recovered and are displayed on the replica museum ship. Given the history and track record of its battleships, it is likely the rebuilt replica is as close as Beijing will go to building another capital warship anytime soon.

Peter Suciu is a Michigan-based writer who has contributed to more than four dozen magazines, newspapers and websites. He regularly writes about military small arms, and is the author of several books on military headgear including A Gallery of Military Headdress, which is available on Amazon.com.