The Taliban is unveiling the government that it now claims represents Afghanistan: Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar will be the Islamic Emirate’s political leader in Kabul, while Haibatullah Akhundzada will be the group’s religious leader in Kandahar.

Diplomats and analysts continue to discuss how various Taliban factions and groups might fill out the remaining ministries and to question whether the Taliban will incorporate other political leaders into a broader tent. Hamid Karzai, the former president known in Afghanistan more for his conspiracies and corruption than for the merits of his previous tenure, has met with the Taliban and may seek a position. So too could former Foreign Minister Abdullah Abdullah. The Taliban have also reportedly offered a position to Ahmad Massoud, the leader of the anti-Taliban resistance in the Panjshir Valley, who made clear he would rather die than accept their offer.

That many American, European, and Indian officials still believe that a broad tent could moderate the Taliban suggest three mistakes: First, a belief that ministerial portfolios matter shows a profound ignorance about the movement nearly two decades after the war began. Second, rather than approach the Taliban and its government with realism, the State Department and many of their counterparts in Europe and India continue to amplify the importance of factions over the reality of the ideology that rogue regimes impose. And, third, too many presidencies and foreign ministries continue to accept the illusion that the Taliban is an indigenous force rather than a foreign proxy operating under Pakistani control which essentially invaded Afghanistan.

Under both Karzai and successor Ashraf Ghani, Afghanistan was Islamic: Islam was the country’s official religion, and Afghanistan drew its laws to conform to with Islamic law. Afghanistan was also a republic: presidents served set terms at the end of which Afghans would head to the polls to either re-elect their president or chose a new leader. It was to this vestige of democracy that the Taliban most objected. Rather than force the government to be accountable to the people, the Taliban seek an Islamic emirate: Politicians serve and subordinate themselves not to the country’s citizens, but rather to a supreme leader and an unelected religious council. The closest parallel is to Iran, where all substantive decisions rest with the supreme leader and where the president and his cabinet contribute more to the regime’s style than its substance. To join the Taliban is to sell out principle and Afghan nationalism for the trappings of a meaningless office.

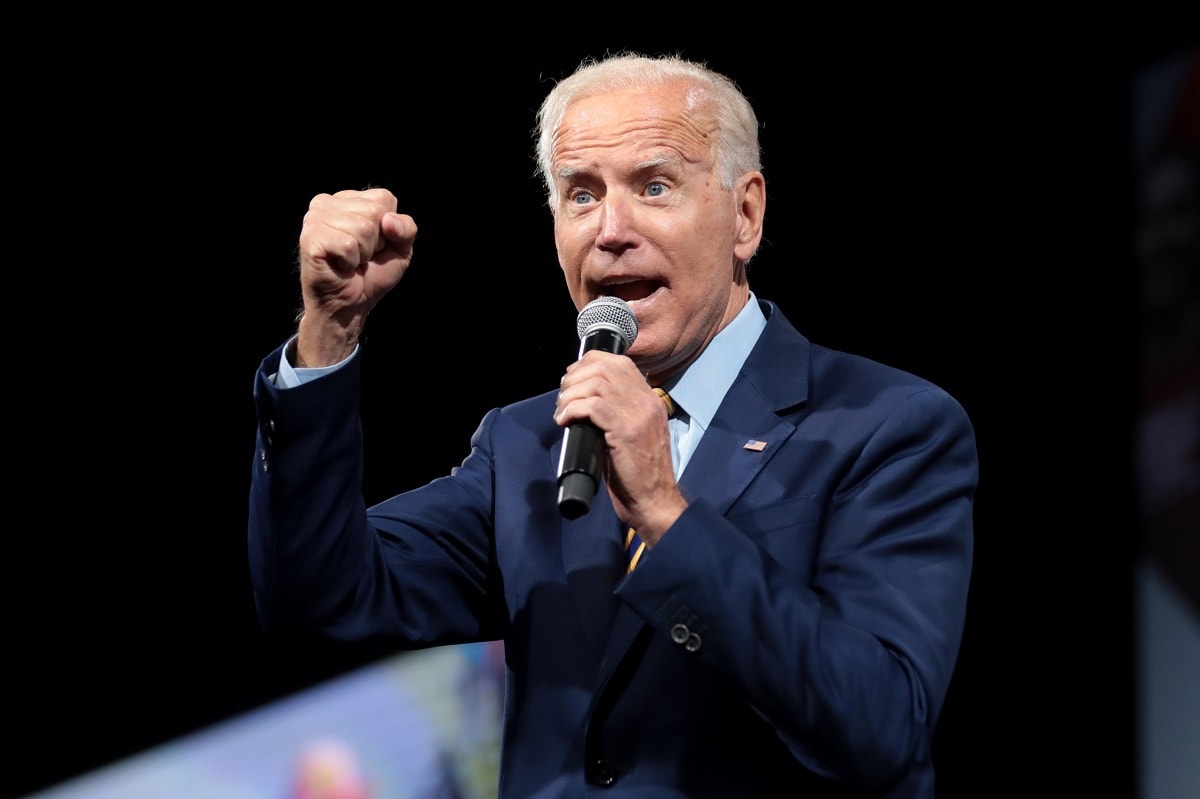

The State Department’s obsession with factions to the detriment of any true appreciation of the import of an opponents’ ideology has long undermined US analysis and policy. Consider Iran: While many politicians and diplomats—President Joe Biden, Secretary of State Tony Blinken, and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan—see sincerity in the Islamic Republic’s reformers, the reality is that even the most soft-spoken Iranian official is subservient to the ideology espoused by late Revolutionary Leader Ruhollah Khomeini and his successor Ali Khamenei. Reformers are simply the good cop to the hard liners’ bad cop. Some reformers admit as much when they speak in Persian and in private. Too often, however, wishful thinking in the West leads Washington to relax pressure to reward reformist rhetoric. This always backfires: Not only did Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs advance most under administrations deemed reformist and moderate by diplomats and the press, but metrics such as executions were also higher. The same would also be true with North Korea: Within the bowels of the Central Intelligence Agency, analysts might engage in Kremlinology to trace the fortunes of those in Kim Jong-un’s inner-circle whom they deem keener to reform, but none of them stands a chance of changing the system in any meaningful way so long as Juche exists.

The last problem afflicting Washington’s analysis is the assumption that the Taliban is indigenous to Afghanistan. In reality, it is a foreign movement whose leaders lived and directed the movement from Pakistan and grew dependent on the resources and instructions of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency. Even those who claim to be Afghan spent nearly the entirety of their lives in Pakistan and maintain families there. The arguments espoused by Special Envoy Zalmay Khalilzad who negotiated the original Taliban pact that the Taliban had grown more nationalist since they mortgaged Afghanistan to trans-national terrorist groups during their 1996-2001 period of control parallel those made by proponents of direct engagement with Hezbollah. A generation of diplomats and intelligence community professionals argued that Lebanese nationalism motived Hezbollah more than Tehran’s ideology, especially after Israel’s May 2000 withdrawal from southern Lebanon. No sooner had the Syrian civil war broken out, however, than Tehran activated its Hezbollah cells to fight in Syria, putting an end to any pretense of the group acting only according to Lebanese interests.

Neither Akhundzada nor Baradar have any ability to counter ISI diktats or commands. In a sense, Akhundzada is less Afghanistan’s spiritual leader than he is its Vidkun Quisling, and Baradar wields no more power to change Pakistani policy than Vichy leader Marshall Philippe Pétain had over Germany. The real leader of Afghanistan today is ISI chief Faiz Hameed.

To engage at all with the Taliban’s Islamic Emirate is to play into Pakistani hands and affirm Islamabad’s fantasies. Instead, it is time the United States put aside its delusions about the Taliban, acknowledge that Biden’s policy was both a surrender and defeat, and acknowledge that the best way forward rests not in placing any faith in moderate Taliban or collaborationists, but rather in supporting the Panjshir resistance and sanctioning Pakistan.

Michael Rubin is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a 1945 Contributing Editor.