When it comes to major economic imbalances, the most dangerous five words that economic policymakers can utter are “this time will be different”. By lulling themselves into a state of complacency with these words, policymakers tend to delay taking policy action that might prevent the exacerbation of those imbalances and a consequent day of economic reckoning.

If ever a country had major economic imbalances it has to be today’s China. And if ever both Chinese and global policymakers are convincing themselves that this time will be different, it has to be in today’s Chinese economic context.

Perhaps the most striking of China’s economic imbalances is its over-dependence on its property sector to drive economic growth. According to estimates by Harvard University’s Kenneth Rogoff, China’s property sector now accounts for close to 30 percent of its overall economy and for around 78 percent of Chinese household’s total wealth. Those ratios are approximately double the corresponding ratios for other major world economies.

Equally troubling has been China’s seeming addiction to credit expansion to sustain its rapid economic growth. According to the Bank for International Settlements, over the past decade, China’s credit expansion to its private sector increased by around a staggering 100 percent of GDP. Such a pace of credit expansion exceeded that which preceded Japan’s lost economic decade in the 1990s as well as that which preceded the US 2008 housing and credit market bust.

Meanwhile, such an excessively rapid pace of credit expansion has spawned a situation where the country has an estimated 65 million uninhabited dwellings and considerable unused industrial capacity.

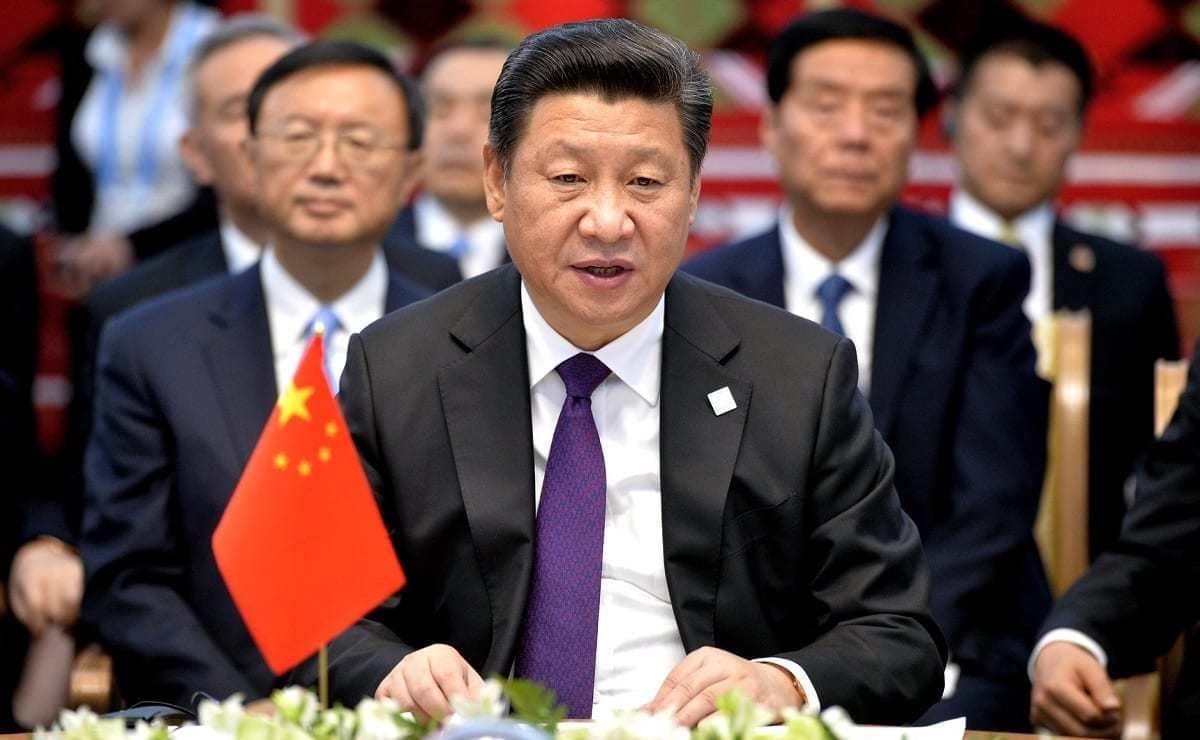

Yet another concerning imbalance has to be the bubble in the country’s housing market. It now appears that property prices in a number of China’s major cities have risen to more than 25 times the average Chinese citizen’s income. This has certainly caught the attention of President Xi who recognizes that housing has become unaffordable for the average Chinese citizen and has been a cause of major income and wealth inequality.

The present acute financial difficulties at Evergrande, the world’s most indebted property developer, have drawn world financial market attention to the unsustainability of China’s current credit and property market-based economic growth model. This is particularly the case as evidence mounts that Evergrande is far from the only Chinese property development company that is flirting with default.

Past experience in many countries that have had smaller housing and credit market bubbles than that of today’s China suggests that those bubbles generally end in tears. They either lead to acute banking and financial market crises as occurred in the United States in 2008 and in Spain in 2010. Alternately, they usher in a prolonged period of sub-par economic growth as occurred in Japan in the 1990s.

To be sure, the Chinese government’s complete control over its banking sector makes it highly improbable that China’s present housing and credit market bubble will lead to the sort of economic and financial market turmoil that followed the bursting of the US housing bubble in 2008.

However, there is every reason to believe that the Chinese government’s use of its banks to prop up its property sector, will result in those banks’ balance sheets becoming clogged with non-performing loans. That in turn will likely starve the economy of the credit needed to transition the economy away from the property sector toward more productive sectors of the economy. This makes it all too likely that China will follow the Japanese economy down the path of an economic miracle being followed by a lost economic decade.

Further clouding China’s economic outlook is President Xi’s “common prosperity program” aimed at improving the country’s income distribution. That program involves an assault on the Chinese private sector in general and its high-tech sector in particular. This seems to constitute a significant reversal of the Deng Xiaoping economic reforms of the late 1970s that were a fundamental component of the subsequent Chinese economic miracle.

In 2008, world economic policymakers were caught flat-footed by the economic and financial market fallout from the Lehman bankruptcy. One has to hope that the same thing will not happen when China moves to a decidedly lower economic growth path and when it will no longer be the world’s principal economic growth engine.

Desmond Lachman is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He was formerly a deputy director in the International Monetary Fund’s Policy Development and Review Department and the chief emerging market economic strategist at Salomon Smith Barney.