The YF-23 is a legend in many military circles. So why did the Air Force pass on it?: For every winner, there is also a second best. When it comes to military hardware there are plenty of designs that were very good, very innovative, and likely would have been more than up to the role required – but there was simply something just a little better.

This is certainly the case of the Northrop/McDonnell Douglas YF-23, or F-23, a fifth-generation, single-seat, twin-engine stealth fighter designed for the United States Air Force in the late 1980s as part of the American Advanced Tactical Fighter (ATF) challenge. The ATF program came about to address the perceived threat from the Soviet Union’s Sukhoi Su-27 and Mikoyan MiG-29, and while several companies originally submitted design proposals, in the end, the USAF opted for designs from Northrop and from Lockheed – which partnered with Boeing and General Dynamics on the YF-22 “Lightning II,” later adapted into service as the F-22 Raptor.

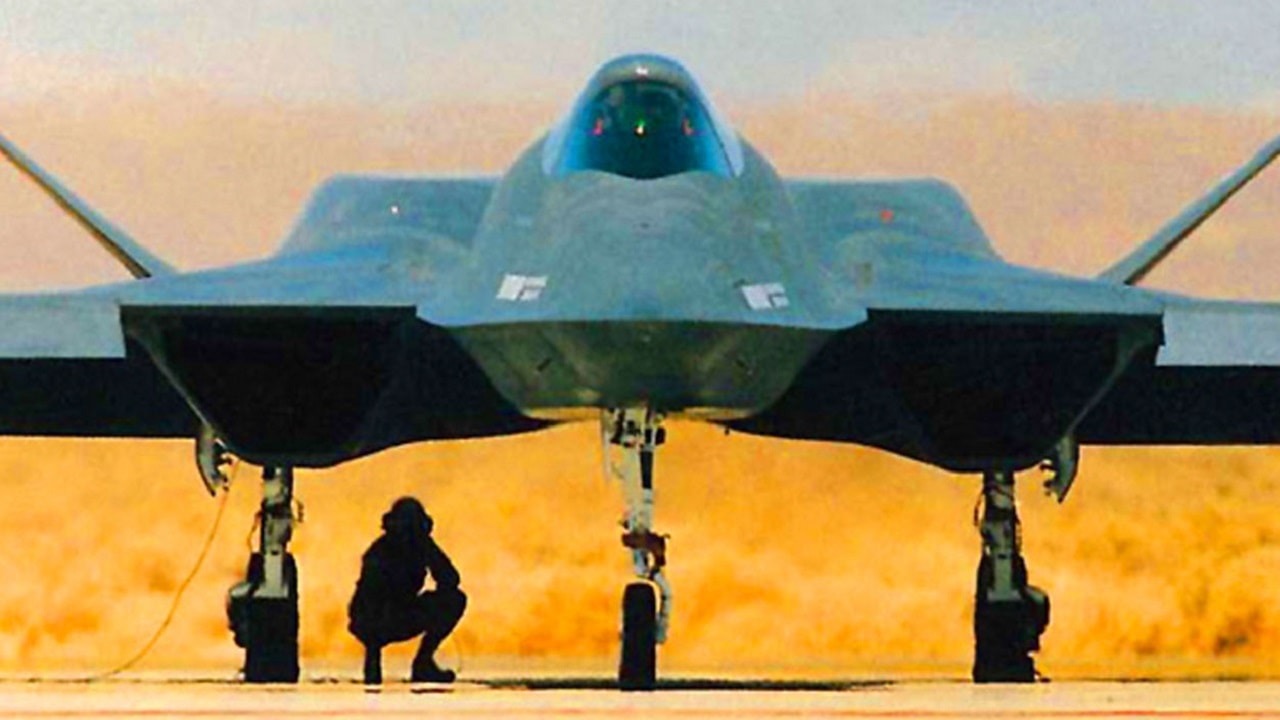

The YF-23’s unique design was quite distinct from the YF-22, and it has been described as having an “almost pancake-like airframe structure with blended wing elements.” Its diamond-shaped wings were meant to reduce aerodynamic drag at transonic speeds.

Two prototypes of the YF-23 were built, each with a different set of engines – as one element of the development phase of the program was to evaluate two experimental turbofan engines. Prototype Air Vehicle 1 (PAV-1), which was painted charcoal gray and unofficially nicknamed “Spider” or “Black Widow II” – in honor of the Northrop P-61 Black Widow flown during World War II – was equipped with the Pratt & Whitney YF199 engines. Prototype Air Vehicle 2 (PAV-2), which was painted in two shades of gray and nicknamed “Gray Ghost,” was powered by a pair of General Electric YF120 engines.

The prototype planes were both fast and stealthy. The plane’s low profile and classified skin material on the airframe was said to be nearly 100% undetectable by nearly any radar system of the period. The “supercruise” function allowed the fighter to achieve sustained supersonic flight without the use of the afterburner.

The designs called for the YF-23 to be armed with a fixed 20mm M61 Vulcan, while internal bays could house four AIM-7 Sparrow or AIM-120 AMRAAM medium-range air-to-air missiles, as well as a pair of AIM-9 short-range missiles.

The YF-23 was very evenly matched with the YF-22. While the YF-23 had a top speed of 1,451mph to the YF-22’s 1,599mph, the Northrop design had a longer range and a higher ceiling – 2,796 miles maximum range and a ceiling of 65,000 feet. By contrast, the YF-22 had a range of 2,000 miles and a ceiling of 50,000 feet.

Where the YF-22 had the edge however was in agility, something that is of the utmost of importance in a fighter aircraft. The YF-22 “Lightning II” was simply better in a dogfight, and that was enough to convince the Air Force that it would be the better of the two.

YF-23 Stealth Fighter. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

YF-23A. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

YF-23. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

YF-23A Artist Rendering. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Image: Creative Commons.

In the end, it wasn’t that the YF-23 was a bad design, nor was it really a losing design. It was really just a classic example of where the competition was just that much better.

Peter Suciu is a Michigan-based writer who has contributed to more than four dozen magazines, newspapers and websites. He is the author of several books on military headgear including A Gallery of Military Headdress, which is available on Amazon.com. This article appeared several years ago.