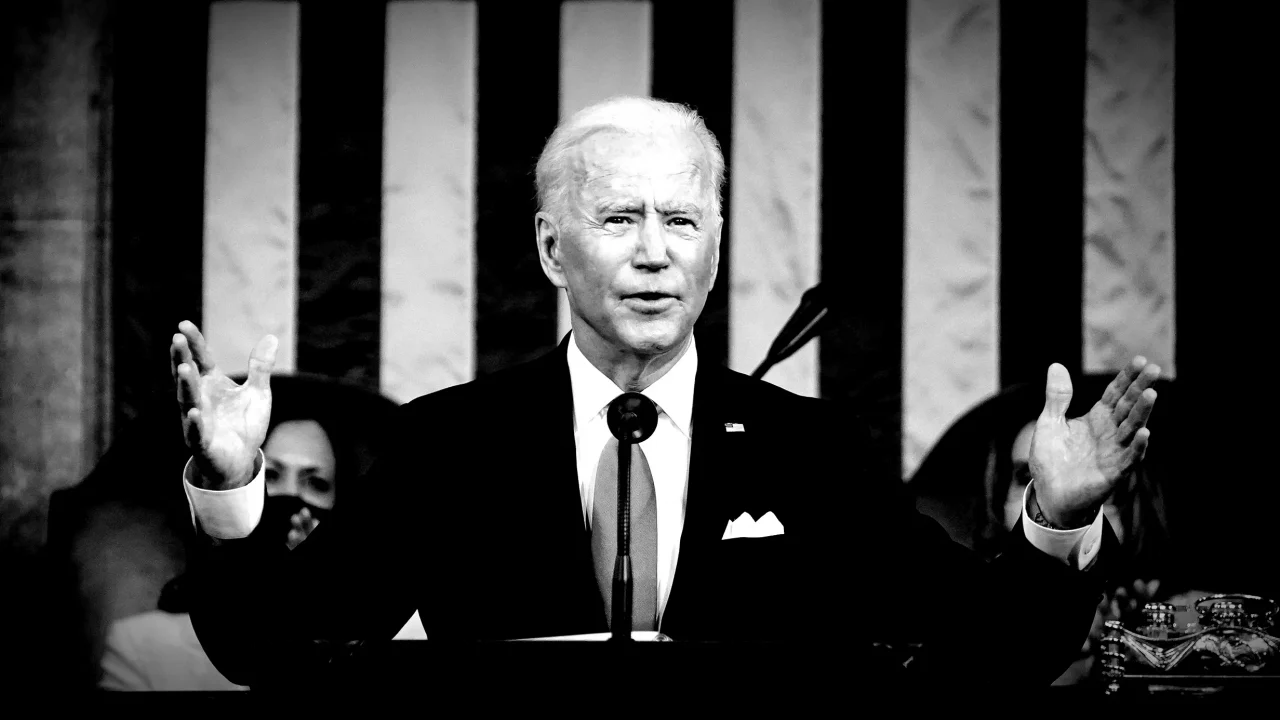

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi is considering capping attendance to President Joe Biden’s State of the Union address to no more than 50 House members. This may be for the wrong reasons—COVID-19 concerns. But it’s a good first step.

The better move would be to just scrap the whole pseudo-event.

The attendance caps would be down from last year when 80 House members attended and 60 senators showed up to hear Biden’s remarks to a joint session of Congress –though not formally a State of the Union speech.

The history of the State of the Union address continues the legacy of one of the nation’s worst presidents and discarding a tradition set by one of our greatest founders.

On some level, the event can be fun for us political junkies. News is often made from a major policy announcement. There are also silly side dramas such as Pelosi ripping up the prepared text of the 2020 address from President Donald Trump, seeing President Barack Obama scold Supreme Court justices over a campaign finance ruling in 2010, and seeing the opposition party response that nearly always flops.

But the whole speech can also be so annoyingly predictable. It is largely the president’s party providing thunderous applause every time he pauses, while the opposition party sets on its hands.

Yes Article II, Section 3, clause 1 says the president “shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.”

However, the Constitution doesn’t require this to be an annual event, only “from time to time.” It doesn’t even require it be an event at all and certainly not a grand political rally that it has become.

When America was an infant nation, Presidents George Washington and John Adams delivered their messages in person to Congress. However, President Thomas Jefferson called delivering the speech “monarchical,” so he sent a written address to Congress. Jefferson likened a speech to a joint session to the British tradition of “a speech from the throne” to open sessions of parliament. He considered this not suitable for a republic.

For more than a century, every president—including towering figures such as Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, and Teddy Roosevelt who knew about shaping public opinion—followed the Jefferson model.

It’s fitting the president whose policies did more to reject the founder’s vision would also reverse the Jefferson precedent on the State of the Union.

In 1913, President Woodrow Wilson, who tended to view the Constitution and Congress itself as barriers to progress, nevertheless delivered his soaring oratory to a joint session for his first State of the Union address that December.

As radio, later TV, and today streaming Internet emerged, there are more avenues to see the event. All this makes it highly unlikely the speech will ever be scrapped.

It is nevertheless long past time to do away with this silly institution, and let the president write a message to Congress—from time to time—about the state of the country.

Can anyone justify why we would want to emulate Wilson over Jefferson?

The pageantry and grandeur of the current day made-for-TV spectacle lifts the presidency into an almost royal-like figure (or maybe less threatening, a sports hero or an Oscar winner) entering the House chamber to massive applause. Moreover, this makes Congress—a co-equal branch—look almost subservient to what the leader of the executive branch says.

That’s not to say there is no utility in this sort of speech.

If the president wants to speak to a televised audience, there are plenty of means for doing so. He could do an Oval Office address anytime. He could even speak to a joint session of Congress from time to time, if the co-equal branches are in agreement about a major national moment that warrants it—such as President Franklin Roosevelt’s speech to Congress after Pearl Harbor, or President George W. Bush’s address to a joint session after 9/11.

The SOTU speech itself too often becomes an issue and distracts from actual national concerns the president and Congress should address. Consider how much White House staff time and Capitol Hill prep time is spent on this one event that could be better spent. It further encourages showboating members of Congress to make the cable news rounds to opine.

Even an audience cap forevermore would only make those members of Congress that don’t attend crave media attention more.

The drama from these speeches, such as the facial expressions of certain members of Congress, or ripping up speeches, may be fun but are not substantive. And there are definite feel-good and patriotic moments such as the president calling out real-life American heroes that deserve recognition—a tradition started by President Ronald Reagan in 1982. But these are all things the president could do at an East Room event.

Perhaps this all seems a bit curmudgeon.

Of course, there are many bigger problems than a speech that will never go away. There are also significantly more concerning areas of executive overreach than this pompous speech. Still floating the audience cap idea finally offers a decent step in the right direction of minimizing such an annual occasion that carries an imperial aura.

Fred Lucas is chief national affairs correspondent for The Daily Signal and the author of “Abuse of Power: Inside The Three-Year Campaign to Impeach Donald Trump.”