Meet the Firefly: At a testing “battle lab” at Fort Benning, Georgia in May, seven U.S. infantry squads trained on and tested a new iteration of the Israeli Spike anti-tank guided missile, diverse variants of which have been extensively exported in Europe and abroad.

Here, rather than pairing the typical launch tube and control system with a sleek armor-busting missile, the new “Spike Firefly” trotted out by arms manufacturer Rafael resembles the stubby, tripod-based sentry guns in the Portal videogame series—except with two rotors so it can lift off and fly around like a helicopter.

And instead of a gun, the docile-looking sensor-equipped mini-copter can blow itself up.

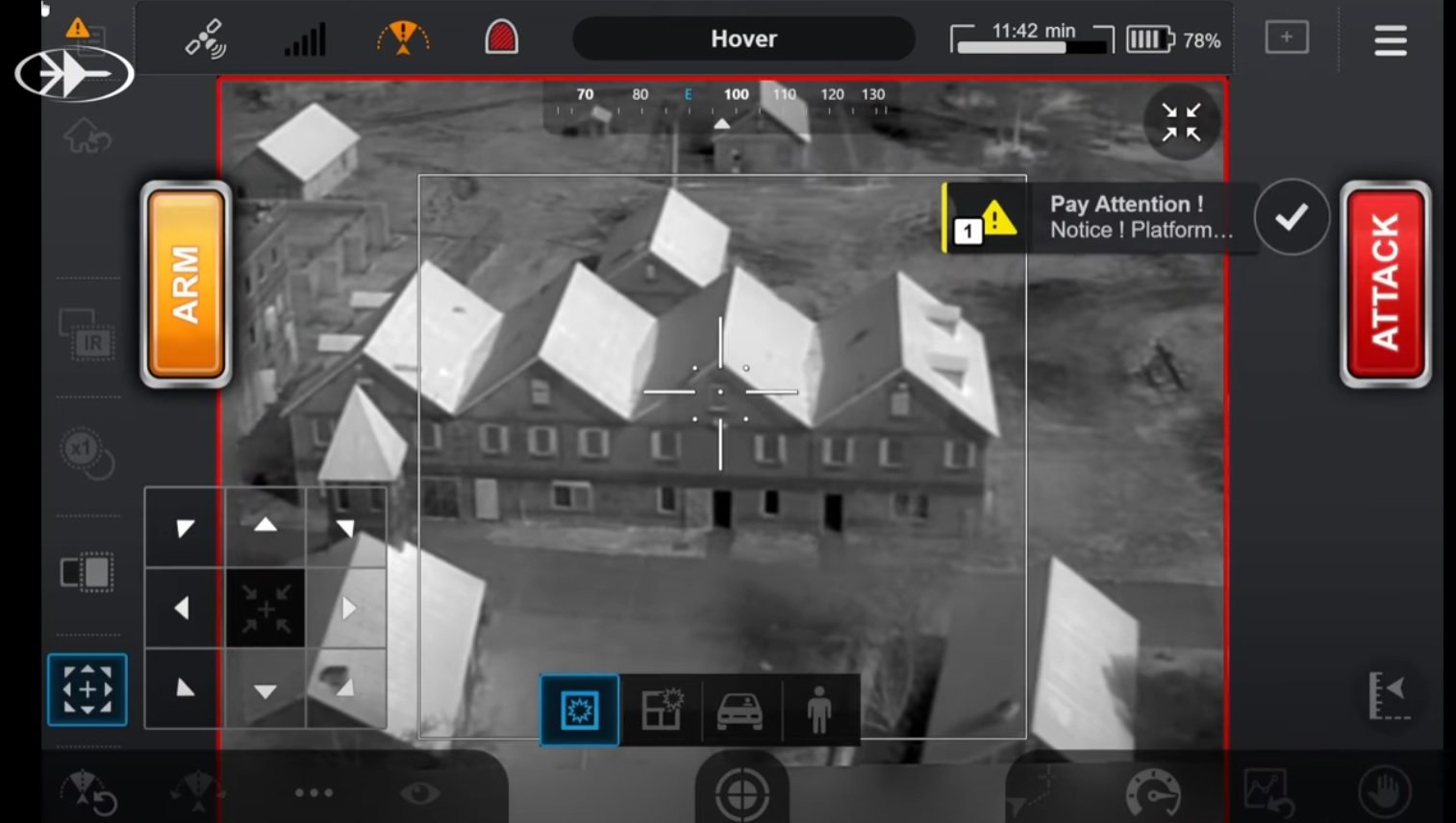

A Rafael promotional video using footage from the battle lab shows how an individual soldier can operate the Firefly drone with a pad controller-style interface and direct it to land on rooftops or dive through windows and explode.

The operator can also instruct the drone to intercept moving targets through the—but also, thanks to its man-in the-loop interface, cancel (“wave off”) the attack if, for example, civilians approach too close to the target.

But was calling this loitering munition part of the “Spike” family simply an exercise in branding?

Daniel Tsemach, Rafael’s international media manager, explained to me that the Firefly shares in common with Spike missiles their day/night electro-optical sensor, the encrypted datalink used to control and receive video imagery, the warheads, and its fuse, and the homing algorithm.

A Firefly system usually includes three 6.6-pound Firefly drones and one 2-pound controller, for a total of 33 pounds. It’s meant to stay relatively close to the grunts on the ground: each Firefly drone has battery for 15 minutes of flight, and its control link is only effective out to .6-1 mile away or .3 miles in an urban environment where tall buildings impede reception. If focusing purely on surveillance missions, an additional battery can be mounted in place of the warhead to double endurance.

Rafael argues Fireflies could be integrated at the infantry platoon level, enabling a lone soldier on foot to dispatch loitering munitions to engage enemies outside of line-of-sight and in cover without having to request air artillery strikes up the chain of command with high potential of collateral damage, or risking a soldiers’ lives engaging a sniper or machine gun nest with direct fire. That’s especially useful in urban warzones where lines of sight are short and cover and concealment are everywhere.

Tsemach wrote to me, explaining that: “The Spike Firefly has significant autonomous capabilities so as not to burden the operator during operation, as we understand that urban combat can be demanding and therefore allows for the soldier to operate and execute a number of tasks.”

That autonomy doesn’t extend to the controversial capability to engage targets without human direction, though. As Tsemach explained regarding Firefly, “…in the final stage of detection, lock and fire, there is a need for the man in the loop.”

That’s arguably a good thing given the discerning judgment needed to mitigate collateral damage and distinguish civilians from combatants in complex urban environments.

Switchblade versus loitering kamikaze helicopters

However, the U.S. Army has already used for years a small tactical loitering munition (AKA a kamikaze drone), the AeroVironment Switchblade-300. And that’s been making headlines recently as the Pentagon transfers hundreds to Ukraine.

Moreover, the tube-launched Switchblade-300 weighs roughly the same as a Firefly but can fly much further to a maximum range of 6 miles, compared to .6 miles for the Spike Firefly.

So why might the Army be considering the Israeli loitering munition despite already using a mature U.S.-based alternative?

A significant difference is that Firefly is a vertical lift aircraft, like a helicopter, allowing it to be used in ways impossible with an aircraft/munition that must move continuously like an airplane. That means a Firefly can land (or “perch”) close to a relevant target area and turn off its rotors to save battery power and surveil an area until it’s deemed appropriate to attack—say when enemies are spotted, or friendly forces are in position.

Landing capability also means it’s easily recoverable and reusable if a target doesn’t present itself, or if used in a reconnaissance-only role. That isn’t guaranteed with other loitering munitions, and Firefly even has a ‘return-to-base’ button. Recoverability and quick-swap batteries make the system effective as a reusable reconnaissance asset.

In addition, because a Firefly can hover (and so even in very windy conditions thanks to its second rotor) it may be better for observing targets in complex urban environments whereas a conventional aircraft would have to glide around in circles, less than ideal if the goal is to monitor what’s happening through a building’s window.

A final difference is that Firefly’s warhead is several times heavier than the Switchblade-300s, increasing its likelihood of disabling personnel or material targets. Certainly, footage from Ukraine suggests the small warheads on tactical loitering munitions may be too weak for guaranteed effect with anything short of a direct hit. That said, the Switchblade’s 40mm-grenade-like munition has a focused, directional warhead to mitigate collateral damage, whereas Firefly’s has a circular blast radius.

Will the U.S. military adopt Firefly?

Following a series of trials in 2020 the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) procured an unknown quantity of Firefly systems as part of the “Momentum” project to integrate more drones and digital technology into the IDF. According to Israeli defense writer Arie Egozie, the Firefly has already been used in combat against insurgents sniping at IDF soldiers from buildings.

The U.S. military is expected to decide soon whether to procure the system. Of course, the Pentagon and Israel have had a close defense relationship for decades, and the U.S. Army is already adopting the SPIKE-NLOS missile for launch from its AH-64 Apache attack helicopters.

However, Israel’s repeated refusals to authorize its clients to transfer different types of Spike missiles to Ukraine could create headwinds for Rafael’s promotion of Spike. That’s because Israel doesn’t want to jeopardize regional deals it has struck with Russia by aiding Ukraine.

That could create concern the U.S. can’t flexibly provide arms procured from Israel to allies, as the Pentagon is currently doing by donating Switchblade drones. However, the Pentagon and Special Operations Command in particular are eager to rapidly integrate loitering munitions and may prefer to acquire a developed system off the shelf.

Sébastien Roblin writes on the technical, historical, and political aspects of international security and conflict for publications including The National Interest, NBC News, Forbes.com, War is Boring and 19FortyFive, where he is Defense-in-Depth editor. He holds a Master’s degree from Georgetown University and served with the Peace Corps in China. You can follow his articles on Twitter.

This piece has been updated since its publication.