On November 27 and 28 2022, tens of thousands of citizens took part in unprecedented protests in major cities and 75 university campuses across China, demanding freedom and an end to zero-COVID policies. This followed violent clashes in Zhengzhou between fed-up iPhone workers and the police. How did it come to this?

After local prevarication in Wuhan in December 2019 and January 2020 about the seriousness of COVID-19, China resorted to an intense national mobilisation campaign to keep the virus under control. This response enabled an economic rebound in late 2020 and 2021.

But China’s zero-COVID response to the Omicron variant after March 2022 has become all-encompassing, unpredictable and economically ruinous. A logic of political control has pushed aside pragmatic health and economic policy. China’s urban public is frustrated.

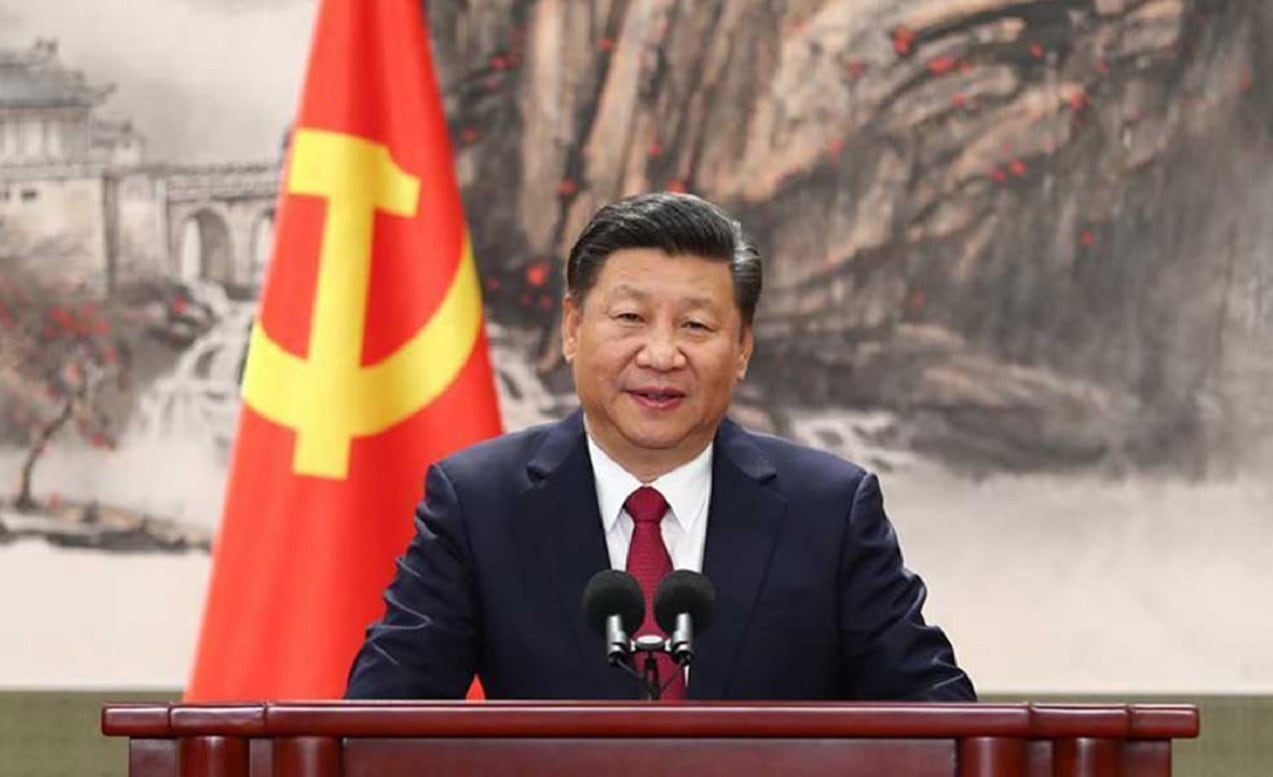

The nature of the Omicron variant and the political calendar played a role in the intensification of technocratic and digital zero-COVID controls. Upholding zero-COVID policies became a performance indicator for officials in China’s political system as they jockeyed for positions before the 20th National Party Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) held from 16–22 October 2022.

COVID-19 was portrayed as a huge threat despite Omicron’s relatively lower pathogenicity compared to earlier variants. Public health measures ramped up, while prominent medical experts and critics of the response were silenced, including former president of China’s Medical Association Zhong Nanshan. COVID-controls became vectors for political control, no matter the mental health or economic costs. When local officials resort to full social control to gain political currency within the Party, as China’s State Council called out in the case of Zhengzhou, it results in policy overreaction, anxiety and uncertainty for the public.

People are repeatedly locked down without prior notice or end dates in sight, as has been the case in cities like Sanya and Guangzhou. Buildings are fenced. People obsess about the colour of their electronic health code. And close contacts (mijie) or digitally-determined potential contacts (shikongbansuizhe) are taken to remote quarantine centres (fancang) for 7–10 days under potentially harsh conditions.

Tragedies are multiplying, prominently in the cities of Lanzhou, Guiyang, Sichuan province, and, most notoriously, in Urumqi, with the death of 10 people trapped in a burning high-rise on 24 November. Individuals’ loss of control over their daily lives proliferates the tang ping (lying flat) attitude. People’s mobility on China’s National Day holiday was disrupted. Businesses cannot plan and China’s youth struggle to find jobs, with youth unemployment sitting at 19 per cent.

Former CCP Secretary of Shanghai Li Qiang presided over the city’s poorly administered lockdown in April. Instead of the policy failures tarnishing Li’s reputation, he was promoted to the second highest position on the CCP’s Politburo Standing Committee and is in line to become China’s premier in March 2023.

Omicron’s relatively greater transmissibility but lower pathogenicity ostensibly increased the costs of zero-COVID closures. Yet to local Party bureaucrats, the opportunity costs of zero-COVID measures may be lower than opening-up, and may be given different weights than they are under democratic political systems. This is because they need to follow the Party’s campaign-style implementation of zero-COVID measures to survive politically.

Other Asian neighbours turned to vaccinations and normalised life during 2022. There was a real cost to this, but one that was seen as lower than the cost of staying closed. For example, between 1 January and 8 November, cumulative deaths per million in Singapore went from 147 to 300. This happened despite a capable medical system and relatively high double vaccination and booster rates with mostly mRNA vaccines of around 90 and 79 per cent respectively.

In contrast, China’s mortality rate is 3.7 deaths per million. Its double vaccination rate (with non-mRNA vaccines) was 89 per cent in November, but booster vaccine doses have only been given to 57 per cent of the eligible population, leaving China vulnerable to future virus waves. The low public trust in China’s vaccines and an unwillingness to import foreign mRNA vaccines leaves China stuck in an Omicron trap.

Six further observations can be made about the politics of China’s pandemic management in 2022. First, the COVID-19 pandemic has become a justification for movement away from China’s past era of reform and opening. Second, COVID-19 controls were not materially relaxed following the CPC’s 20th National Party Congress. Although China’s National Health Commission released a memo on optimising COVID-19 response measures, there have been few major changes in COVID-19 management so far.

Third, 2022 has exposed China’s deficits in healthcare, welfare and mental health supports. It has also demonstrated China’s capacity in surveillance, digital control and policing. Fourth, the international appeal of China’s human security discourse that emphasises human life over individual freedom remains doubtful considering the painful human experiences China’s people endure.

Fifth, 2022 has seen a fragmentation and localisation of China’s economy, as local officials implement zero-COVID measures in an ‘overly-firm manner’ (zuofeng guoying) to signal political loyalty towards China’s President Xi Jinping. Human exchanges have been reduced between China and the world (despite a slight loosening in quarantine policies for people entering China), and within China. Local languages are making a resurgence. Sixth and overall, export-oriented cities like Shenzhen have faced lighter restrictions than financial centres like Shanghai and Hong Kong.

At the close of 2022, despite the zero-COVID measures, Omicron is spreading across China. The Standing Committee of the Chinese Communist Party’s Politburo reaffirmed its policy approach, but citizens are exhausted. Their anger finally spilled over on November 27–28 in an outburst of social medial rebellion and protests across China, taking the party leadership by surprise. China’s economy is underperforming compared to the rest of Asia for the first time since 1990.

Whether China can find a pragmatic and peaceful way out of its zero-COVID approach remains an open question.

Dustin Lo is a MA candidate in political science and research assistant at the University of British Columbia.

Yves Tiberghien is Professor of Political Science and Director Emeritus of the Institute of Asian Research at the University of British Columbia. He is also a Distinguished Fellow at the Asia-Pacific Foundation of Canada.

This first appeared in East Asia Forum.