In March 2005, the National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China passed an anti-secession law reaffirming Beijing’s One China Principle: that Taiwan is a fundamental part of China and that if the “possibilities for a peaceful reunification should be completely exhausted the state shall employ non-peaceful means and other necessary measures to protect China’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.” In August 2022, the PRC released a white paper stating a preference for peaceful reunification with Taiwan under a “One Country, Two Systems” principle, but it refused to renounce the use of force against “external interference and all separatist activities.”

Taiwan’s official response was to claim the anti-secession measure violated international laws guaranteeing a state’s sovereign rights and its right to self-determination, as well as the prohibition on the threat or use of force in international relations. The United States has consistently called for a peaceful resolution to the Taiwan question, affirming that wish in its three joint communiques with the PRC. At the same time, Washington has pursued a One China Policy that is ambiguous on the nature of Taiwan and whether the U.S. will defend it. Is this merely policy, and thus fungible, or is there a principle in Washington’s stance?

Buffer or Bridgehead?

In addition to its aboriginal population, the island of Formosa, now known as Taiwan, has hosted a Dutch trading outpost, a pirate kingdom, an imperial prefecture and later province, a Japanese colony, and the former government of mainland China. At some point during this history, Taiwan is said to have become part of China. While more than 95% of Taiwan’s population identifies as Han Chinese, the question remains of how, exactly, Taiwan became Chinese.

Alan M. Wachman, in his book Why Taiwan?, tells the history of Formosa and describes the island as alternatively a buffer or bridgehead. Dutch traders wanted to establish a trading port similar to what the Portuguese had in mainland China. Ming Dynasty officials were not comfortable with this and directed them to Formosa, an island populated by aborigines. Wachman argues that the Ming Dynasty did not view Formosa as an integral part of China. This would change with the defeat of the Ming Dynasty by the Manchu and the establishment of the Qing Dynasty.

The Dutch were forced to leave Formosa in the mid-17th century due to the pirate fleet of Zheng Chenggong. Zheng established his own kingdom on Formosa in defiance of the Qing Dynasty. This kingdom would last 20 years before the island was conquered and absorbed into China.

Image: Creative Commons.

Shi Lang, the admiral who conquered Formosa, argued that China should settle the island. Wachman describes the “Shi Lang doctrine,” according to which if China does not hold Formosa, another power could occupy the island and use it as a bridgehead to threaten southern China — just as the pirates did. If China occupied the island, however, it could flip that dynamic, using Formosa as a buffer to defend southern China.

War in Korea, Japanese Colony, and World War II

Japan eventually challenged imperial China’s control over Korea, defeating them in the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895. The resulting Treaty of Shimonoseki transferred the present-day territory of Taiwan to Japan, who administered it as a colony until 1945.

The concept of Taiwan as an integral part of China seemed to leave public consciousness during this time. As Wachman noted, “No Chinese government — Qing Empire, Nationalist Republic, or Communist Soviet — had a realistic chance of restoring sovereignty over the island.”

This would change with World War II, when the Republic of China’s leader, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek, made it a war aim to reverse the Treaty of Shimonoseki and other unequal treaties. The Communist Party of China did the same with its Declaration on the War in the Pacific, issued on Dec. 9, 1941.

On Nov. 26, 1943, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt joined Chiang Kai-Shek and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to issue a statement known as the Cairo Declaration. The Declaration reversed all Japanese territorial gains since the First World War and confirmed “that all the territories Japan has stolen from the Chinese, such as Manchuria, Formosa, and the Pescadores, shall be restored to the Republic of China.” After the conclusion of the war in Europe, the United States, United Kingdom, and Soviet Union repeated this aim with the Potsdam Declaration, noting “Japanese sovereignty shall be limited to the islands of Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, Shikoku and such minor islands as we determine.”

Suspended Civil War

The current debate over Taiwan is the result of a suspended civil war. Republic of China forces fled the mainland after the Communists proclaimed the PRC in December 1949. The United States viewed ROC forces as merely occupying Taiwan after the Japanese surrender at the end of the Second World War. With the North Korean invasion of South Korea on June 25, 1950, the United States immediately changed its policy of not defending Taiwan. The Truman administration feared the spread of Communism and sent the U.S. 7th Fleet to the Taiwan Strait to prevent the PRC from invading Taiwan or ROC forces from attempting to retake the mainland. This intervention created the status quo that exists today of two governments claiming to represent the island’s people. Taiwan remains a bridgehead to the Chinese mainland, threatening lines of communication in the strait and possibly southern China.

The United States ensured that Taiwan’s status would remain ambiguous with the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty, which formally ended the war with Japan. The PRC and ROC did not participate in treaty negotiations. Japan renounced its “right, title and claim to Formosa and the Pescadores islands.” This territory was not ceded to any other country. ROC forces have been occupying the territory since Japan’s surrender in 1945.

One China Principle

It took nearly 25 years for the PRC to receive international recognition as the legitimate government of China. This occurred amid the decolonization period following the Second World War and the admission of new countries to the United Nations. The liberated Global South would provide the PRC with the diplomatic support it required to emerge on the world stage. The PRC successfully raised the One China Principle to the international community with the passage of United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2758, which recognized the PRC as the “only lawful representatives of China to the United Nations” and expelled “the representatives of Chiang Kai-shek from the place which they unlawfully occup[ied] at the United Nations and in all the organizations related to it.”

Image: Creative Commons.

The road to the One China policy began, from the American perspective, with the administration of President Richard Nixon in 1969. Secret visits to China by National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger led to President Nixon’s visit to the PRC in February 1972. This visit resulted in the Shanghai communique, with the United States acknowledging that “there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part of China.” The United States called for a “peaceful settlement to the Taiwan question by the Chinese themselves” and declared that the United States would “progressively reduce its forces and military installations on Taiwan as the tension in the area diminishes.”

Thus was formed the core of Strategic Ambiguity. The United States would lessen its support to Taiwan, leaving the issue for the Chinese people to resolve.

A key feature for countries establishing diplomatic relations with the PRC is expressly stated support for the One China Principle. The promise for peaceful reunification that was present in the United States-PRC joint communique is not necessarily included in these diplomatic agreements — for instance, the United Kingdom-PRC joint communique did not include this requirement. In 1972, British Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, Sir Alec Douglas Home, stated, “We held the view both at Cairo and at Potsdam that Taiwan should be restored to China. That view has not changed. We think that the Taiwan question is China’s internal affair, to be settled by the Chinese people themselves.” Similarly, the Australian-PRC joint communique establishing diplomatic relations did not mention the peaceful reunification of Taiwan with China. The PRC’s One China Principle has successfully isolated Taiwan, with Honduras being the most recent country to sign on.

The argument for Taiwan’s sovereignty or independence from the PRC was weakened when Japan established diplomatic relations with the PRC in September 1972. The Japanese-PRC joint communique recognized the PRC as the sole legal government of China and declared Taiwan “an inalienable part of the territory of the People’s Republic of China.” The Treaty of Taipei between Japan and the ROC would have no further effect.

One China Policy and Strategic Ambiguity

The United States’ One China Policy differs from the PRC’s One China Principle. A careful reading of the three joint communiques reveals subtle differences. In the first communique, the United States “reaffirm[ed] its interest in a peaceful settlement of the Taiwan question by the Chinese themselves” and promised only a gradual withdrawal of U.S. military forces from Taiwan. The second communique was more in line with the PRC’s One China principle, but the Taiwan Relations Act (TRA) passed in its wake committed the United States to selling weapons to Taiwan. In the third communique, the United States clarified that it did not have a “long-term policy of arms sales to Taiwan.”

The third communique caused President Ronald Reagan to issue the Six Assurances to Taiwan. The United States would continue arms sales without consulting with the PRC and would not change the TRA. It is interesting to note that there were different public and classified versions of the Six Assurances. The United States’ One China Policy is to disclaim any role in mediating the Taiwan question, while providing “defensive weapons” to Taiwan to help it resist forceful reunification.

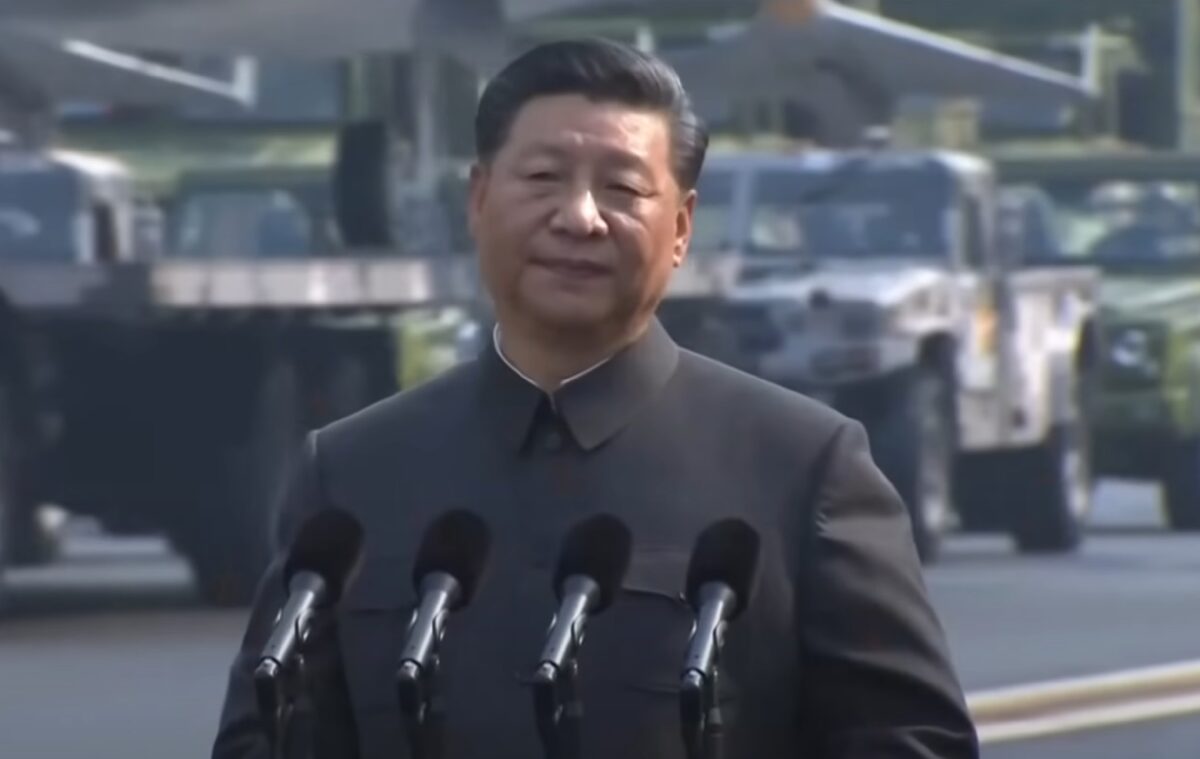

Image: Screenshot from CCTV/Chinese State TV.

The United States has maintained strategic ambiguity in its commitments to Taiwan. The TRA is a policy statement, not a commitment to defend Taiwan. It was the policy of the United States to “consider any effort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means, including boycotts or embargoes, a threat to the peace and security of the Western Pacific area and of grave concern to the United States.”

The “arms of a defensive character” must be approved by Congress and the president. There is no open shopping list for Taiwan to access at will. The Act’s definition of Taiwan is also limited to Taiwan and the “Pescadores islands” excluding other islands such as Matsu and Kinmen that are close to China’s mainland. These islands may be difficult to defend if invaded and could be considered sovereign territory of China long before Formosa was settled.

Maintaining the Status Quo

The Taiwan question remains unresolved. The United States and Taiwanese authorities seem content to maintain the status quo and not provoke the PRC. The Kuomintang party that ruled Taiwan for decades held on to the idea of One China, but the democratization of Taiwan led to the emergence of the Democratic People’s Party (DPP). It remains to be seen whether the DPP will push for independence or continue the status quo. Cross-strait economic and cultural ties have increased. As the decades pass and former mainlanders are replaced with younger generations who have their own ideas on Taiwan’s relations with the mainland, one wonders if the One China Principle may one day replace the One China Policy.

Lt. Col. Brent Stricker, U.S. Marine Corps, serves as a military professor of international law at the Center for Naval Warfare Studies, U.S. Naval War College. The views presented are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of the U.S. Marine Corps, the U.S. Navy, the Naval War College, or the Department of Defense.