Endorsed! This month over at the Naval Institute Proceedings, coastguardsman Steve Hulse urges the U.S. Navy to procure a flotilla of Sentinel-class fast response cutters (FRCs) to serve as missile patrol craft.

He sketches a compelling brief. Read the whole thing.

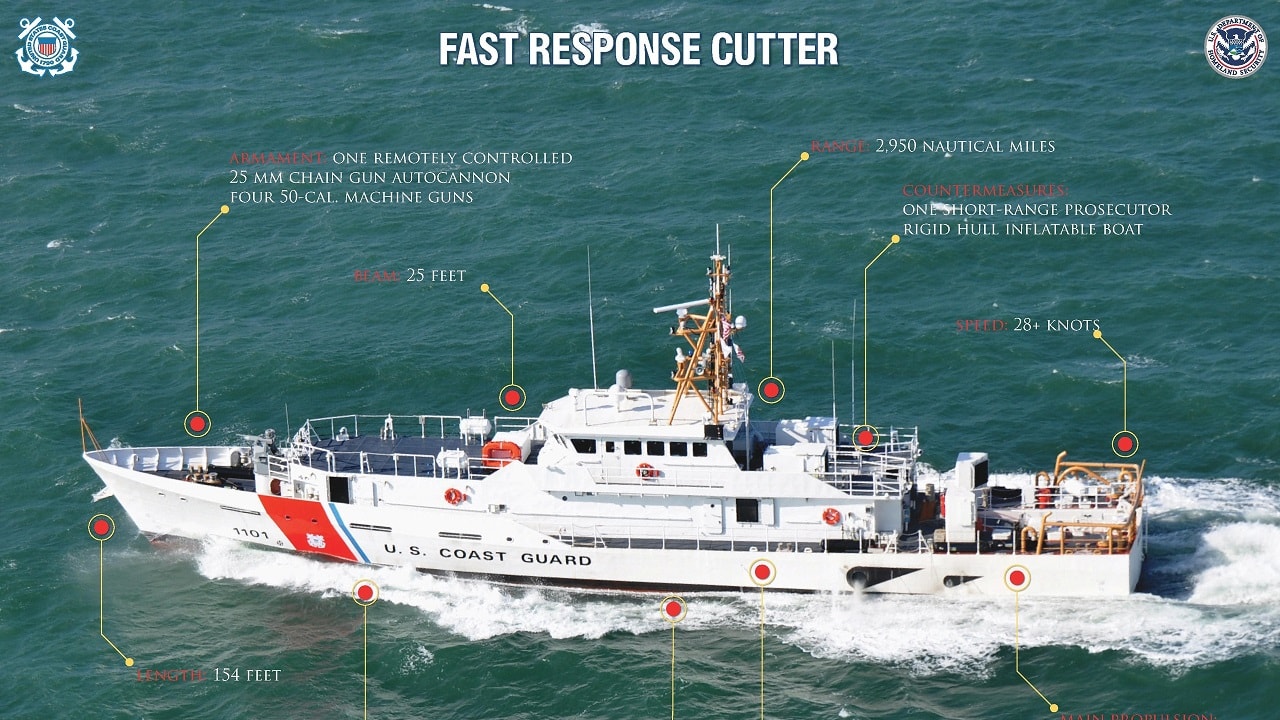

By swapping out the cutter boat typically carried on board U.S. Coast Guard FRCs for a box launcher packing anti-ship Naval Strike Missiles, says Commander Hulse, shipwrights could transform the 154-foot Sentinel class—a lifesaving and law-enforcement craft—into a surface combatant that punches above its weight. (The missile launcher weighs slightly less than the boat, making such a swap feasible without impairing the vessel’s stability.) Moreover, the coast-guard variant has demonstrated the ability to launch and recover unmanned aerial vehicles. That would be indispensable for detecting, tracking, and targeting hostile ships of war within missile range but beyond the horizon.

Repurposing the fast response cutter would bestow other advantages. Hulse notes that the production line for these winsome craft is “hot,” meaning it is still turning out copies for the U.S. Coast Guard. It should be a straightforward matter for the navy to order more from shipbuilder Bollinger Shipyards, keeping the line hot. And the price is right. The latest FRCs are coming in at $65 million per hull, compared to over $1.2 billion for the navy’s new Constellation-class frigate or around $2 billion for the latest upgrade of the venerable Arleigh Burke-class destroyer. Sounds like twenty missile patrol craft for the price of one Constellation, or thirty for the price of a Burke. That’s bang for the buck. Surely Congress can scrounge up the extra dollars for a flotilla.

Hulse charts a viable route to affordable mass at sea, to borrow a slogan now in vogue. Mass is indispensable in warfare. Quantity is no substitute for quality, but it does have a quality all its own. Affordability is likewise indispensable in a cost-constrained age such as our own. Without it you can’t buy in bulk.

Nor should building a flotilla detract from existing acquisitions. Bollinger Shipyards doesn’t build major surface combatants, so producing a clutch of fast response cutters there would not siphon matériel or skilled labor from other important projects the way it would at, say, Bath Iron Works in Maine or Huntington-Ingalls in Mississippi, which build destroyers and other major surface combatants. Leveraging smaller shipyards is a must for the U.S. Navy. The defense-industrial complex and the U.S. government allowed the nation’s shipbuilding infrastructure to atrophy in the years following the Cold War. That’s one of the hazards of claiming a peace dividend in the wake of a major victory: the armed forces tend to shrink dramatically. Placing fewer orders for major weapon systems tends to contract the manufacturing base, meaning the foundation for regenerating combat power in a hurry may not be there when the next strategic challenger comes along. As it will, world politics being what it is.

So past folly forces you to improvise and innovate in the here and now—including by conscripting offbeat partners in the enterprise. If major suppliers can’t provide you with big ships, small ones will have to do.

But the case for missile patrol craft isn’t all about penny-pinching or circumventing industrial woes. These are the right ships to help carry out U.S. maritime strategy in congested coastal terrain such as the Western Pacific, in wartime and times of tense peace alike. Denying an antagonist like China’s navy access to waters around and between Pacific islands is the strategy’s beating heart. Swarms of small, cheap, lethal surface and subsurface warships working with aircraft overhead and troops on the islands can close the straits along the first island chain, laying fields of overlapping fire that imprison Chinese sea and air forces within the island chain and bar the return home to units plying the Western Pacific. For self-defense, small surface combatants can mingle with merchant traffic amid East Asia’s cluttered maritime geography. In so doing they obscure their whereabouts and turn ambient conditions to tactical advantage. Let Chinese rocketeers try to distinguish friend from foe.

By swarming coastal seaways, in short, the flotilla would supply an enabler for the main fleet’s endeavors. Corral the foe with flotilla craft and let the battle fleet and the U.S. Air Force pummel it.

And what better platform than a superempowered coast-guard cutter slathered in haze gray to help U.S. allies in Asia compete in the gray zone, that competitive arena short of open combat, defending their sovereign rights to offshore natural resources? Joint coast-guard patrols are reportedly preparing to take to contested waters in the next few months. Just imagine the fits the allies could give China’s maritime militia and coast guard if the first layer of U.S. Navy backup for law-enforcement patrols were a flotilla of converted cutters packing heat.

Unfortunately, it may take a cultural revolution among the U.S. Navy leadership for any of this to happen. This remains a Mahanian force beloved of oceangoing, multimission, pricey capital ships, not unglamorous patrol craft. Nor, as a rule, is it especially receptive to change. As Franklin Roosevelt, who served as assistant secretary of the navy, once wisecracked: “To change anything in the Na-a-vy is like punching a feather bed. You punch it with your right and you punch it with your left until you are finally exhausted, and then you find the damn bed just as it was before you started punching.”

FDR would nod knowingly were he among the quick today. Navy prelates talk about “distributed maritime operations,” as they have for the better part of a decade. To oversimplify a trifle, that means scattering firepower among a much more numerous fleet and concentrating it at points of impact for battle. The result is a more resilient force, able to lose one or a few ships in action without losing its overall fighting capacity. But to make a distributed fleet affordable the navy must add a contingent of inexpensive, single-mission vessels capable of hitting hard. Just ask the grandmaster of fleet tactics, the late and lamented Captain Wayne Hughes.

To all appearances this is all accepted wisdom in the service. However sincere they are about distributed warfare, though, navy leaders’ hearts have never seemed to be in it. They say the right things, but somehow the fleet’s force structure and operating practices stay mostly the same. “If it floats, it fights” was a navy mantra for awhile. But no one has mounted anti-ship missiles on amphibious transports or logistics ships in the interim, turning a sound idea into steel. The navy has taken a tepid attitude at best toward fielding medium landing ships the U.S. Marine Corps needs to ferry missile-armed troops around island chains to make things rough on an opponent while helping the U.S. fleet deny, win, and exercise command of regional waters. There’s little if any appetite for low-cost diesel attack submarines suitable for lurking in littoral seas. The navy is even jettisoning youthful, shallow-draft littoral combat ships at a time when their engineering travails finally seem to have been sorted out.

So the logic of small surface combatants is impeccable, and gray-hulled fast response cutters are a prime candidate for the job for operational, tactical, industrial, and budgetary reasons. Hulse is correct. We just need leadership from the uniformed navy, its civilian masters, and Congress with the willpower to put ideas into practice. And we need it pronto.

As a wise man said recently, just build some **** ships.

About the Author and His Expertise

Dr. James Holmes is J. C. Wylie Chair of Maritime Strategy at the Naval War College and a Distinguished Fellow at the Brute Krulak Center for Innovation & Future Warfare, Marine Corps University. The views voiced here are his alone.

From the Vault

The Navy Sent 4 Battleships To Attack North Korea

‘Sir, We Hit a Russian Submarine’: A U.S. Navy Sub Collided with a Nuclear Attack Sub