Key Points and Summary: Canada’s naval surface fleet is at a critical juncture, with aging Halifax-class frigates and inadequate Arctic capabilities threatening maritime security and sovereignty. The Canadian Surface Combatant program aims to replace aging vessels with advanced warships, but delays and cost overruns raise concerns.

-Canada’s Arctic ambitions also demand specialized assets like icebreakers and polar-ready ships. A comprehensive strategy must prioritize fleet modernization, Arctic-specific capabilities, collaboration with allies, and Indigenous partnerships.

-These efforts are vital to maintaining Canada’s maritime presence, countering geopolitical threats from Russia and China, and asserting sovereignty in the rapidly changing Arctic region.

Canada’s Aging Navy: Why Surface Fleet Modernization Is Urgent

The Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) is at a crossroads. Canada’s naval surface fleet, which has long been a cornerstone of its maritime security and sovereignty, is increasingly ill-equipped to meet the demands of modern naval operations. As global challenges evolve, particularly in the Arctic, the inadequacies of Canada’s surface fleet are becoming glaringly apparent.

To maintain its status as a credible maritime power, Canada must modernize its naval capabilities and address the systemic issues that threaten to undermine its security and strategic objectives.

Canada’s surface fleet is aging. The Halifax-class frigates, once the pride of the RCN, are nearing the end of their operational life. Introduced in the early 1990s, these frigates were designed for a different era, and while mid-life upgrades have extended their usability, they are no match for the technological and operational demands of the 21st century. Similarly, the Kingston-class maritime coastal defense vessels lack the range, endurance, and capabilities needed for modern naval engagements, let alone the unique challenges of Arctic operations. These aging platforms not only limit Canada’s ability to project power but also hinder its capacity to respond effectively to emerging threats.

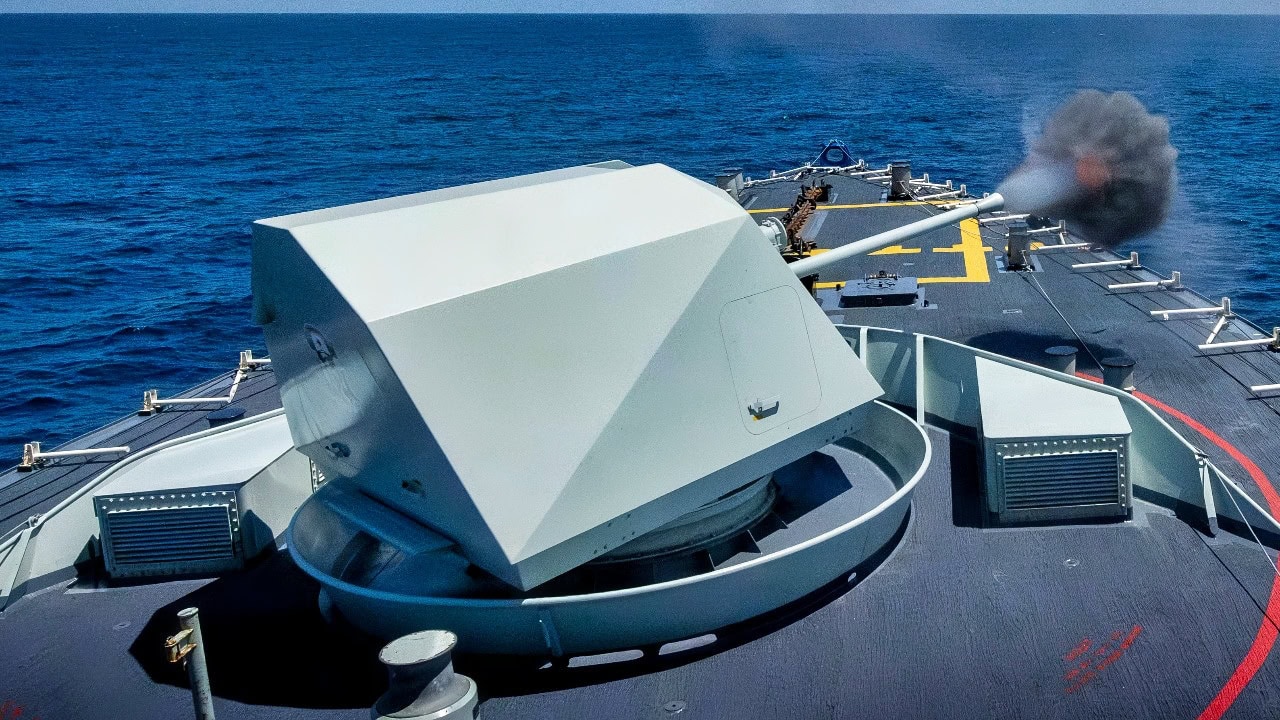

The Canadian Surface Combatant (CSC) program is intended to address these shortcomings by replacing the aging Halifax-class frigates with up to 15 state-of-the-art warships. These vessels, based on advanced designs like the British Type 26 frigate, are expected to feature cutting-edge sensors, weapon systems, and propulsion technologies. They will be capable of operating in diverse maritime environments, from the Pacific to the Arctic.

However, the program has been beset by delays and cost overruns, with lifecycle costs now projected to exceed CAD 300 billion. This raises serious questions about Canada’s ability to deliver the ships on time and within budget, threatening the RCN’s operational readiness.

While the CSC program is essential, it is not a panacea. Canada’s Arctic ambitions require more than a modernized fleet of surface combatants. The Arctic is an environment unlike any other, demanding specialized capabilities such as ice-strengthened hulls, advanced navigation systems for polar conditions, and robust logistical support for sustained operations in remote and inhospitable regions. Without these enhancements, even the most advanced surface combatants will struggle to operate effectively in the Arctic.

Polar icebreakers are another critical component of Canada’s Arctic strategy. These vessels are indispensable for maintaining sovereignty, enabling scientific research, and ensuring the safe navigation of increasingly accessible shipping routes. Yet, Canada’s icebreaker fleet is outdated and inadequate. Investing in a new generation of Arctic-capable icebreakers is not merely a matter of national pride but a strategic necessity. Without these assets, Canada risks ceding strategic ground to more ambitious players like Russia, which has deployed a formidable fleet of Arctic-capable vessels.

Canada’s strategy must also reflect a commitment to geopolitical restraint. While the militarization of the Arctic by powers like Russia and the growing influence of China demand vigilance, Canada should resist the temptation to escalate through an arms race. Instead, it must focus on building a persistent and credible presence in the region, leveraging advanced surveillance systems, modernized warning infrastructure, and multi-role naval platforms. Sovereignty is not claimed through saber-rattling but demonstrated through consistent and meaningful action.

Collaboration with allies will be critical in addressing the challenges facing Canada’s surface fleet and its broader Arctic strategy. The modernization of NORAD offers a valuable opportunity to enhance domain awareness and improve coordination in the face of shared threats. Strengthening ties with NATO allies, particularly those with Arctic interests, can amplify Canada’s capabilities while distributing the financial and operational burdens of securing the region.

Moreover, Canada must continue to champion multilateral diplomacy through forums like the Arctic Council, reinforcing the Arctic’s status as a zone of cooperation rather than conflict.

Indigenous communities must play a central role in shaping Canada’s Arctic policies. The Inuit and other Indigenous peoples are not merely stakeholders but stewards of the Arctic’s environment and culture. Their traditional knowledge and lived experience are invaluable in crafting sustainable and inclusive policies. By prioritizing investments in Indigenous communities, Canada can build trust and strengthen its legitimacy in asserting Arctic sovereignty.

The condition of Canada’s naval surface fleet is a reflection of the nation’s broader strategic priorities. Without decisive action to modernize its fleet, acquire Arctic-specific capabilities, and adopt a coherent and sustainable strategy, Canada risks undermining its maritime security and diminishing its influence on the global stage.

The choices Canada makes today will determine whether it can rise to the challenge of becoming a leading Arctic power or whether it will be left behind in an era of rapid geopolitical change.

Canada’s Navy: A Story in Photos

Victoria-Class Submarine at Sea. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Victoria-Class Submarine Canada.

Victoria-Class Submarine from Canada.

Victoria-Class Submarine Canadian Navy. Image Credit: Government Photo.

Canada Victoria-Class Submarine. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

(Dec. 12, 2011) The Royal Canadian Navy long-range patrol submarine HMCS Victoria (SSK 876) arrives at Naval Base Kitsap-Bangor for a port call and routine maintenance. The visit is Victoria’s first to Bangor since 2004. (U.S. Navy photo by Lt. Ed Early/Released)

The Canadian frigate HMSC Toronto, seen here docked in Odessa, Ukraine, participated in Exercise Sea Breeze 2019, a multinational maritime exercise co-led by the United States and Ukraine. Nineteen nations participated, including 15 NATO Allies.

About the Author: Andrew Latham

Andrew Latham is a non-resident fellow at Defense Priorities and a professor of international relations and political theory at Macalester College in Saint Paul, MN. Andrew is now a Contributing Editor to 19FortyFive.