Summary and Key Points – Railguns promised hypersonic projectiles, deep magazines, and low cost per shot, but the concept collapsed under shipboard reality: massive power bursts, heat, cooling limits, accuracy challenges, and punishing barrel erosion.

-The deeper issue was integration—Burke-class ships were never built for railgun energy demands, and even Zumwalt’s power margin proved finite once competing systems were considered.

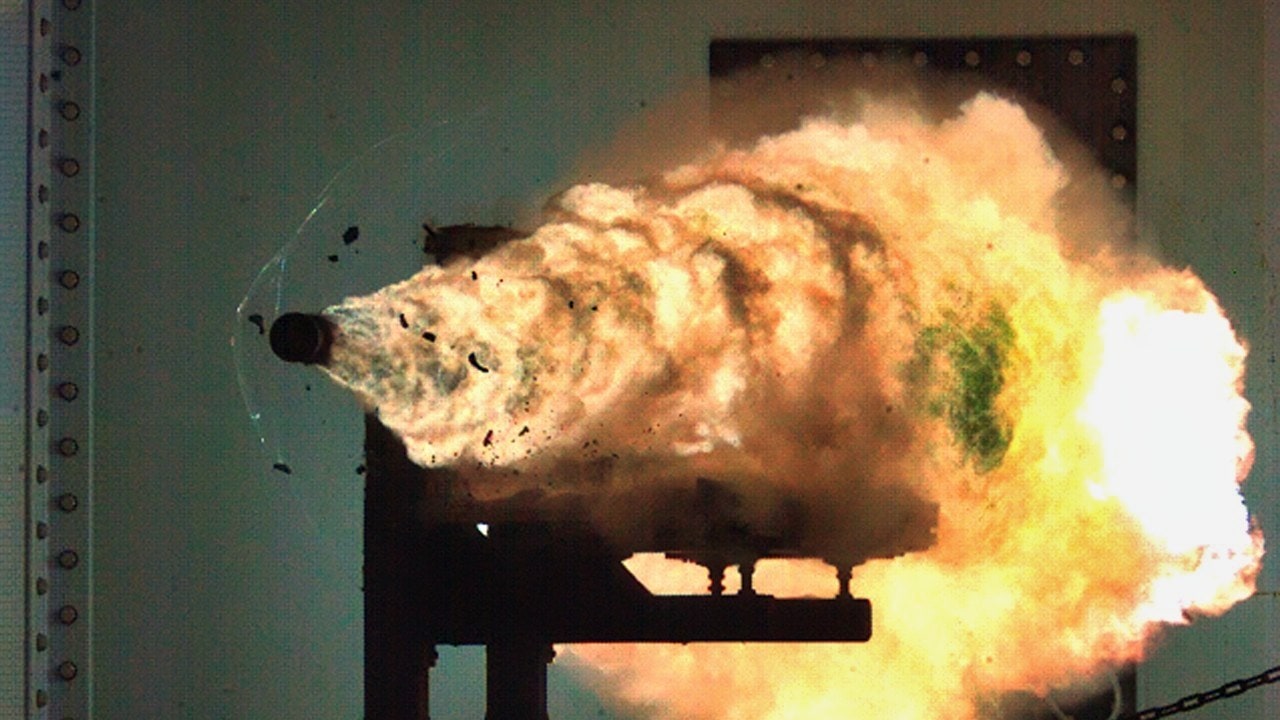

(Jan. 31, 2008) Photograph taken from a high-speed video camera during a record-setting firing of an electromagnetic railgun (EMRG) at Naval Surface Warfare Center, Dahlgren, Va., on January 31, 2008, firing at 10.64MJ (megajoules) with a muzzle velocity of 2520 meters per second. The Office of Naval Research’s EMRG program is part of the Department of the Navy’s Science and Technology investments, focused on developing new technologies to support Navy and Marine Corps war fighting needs. This photograph is a frame taken from a high-speed video camera. U.S. Navy Photograph (Released)

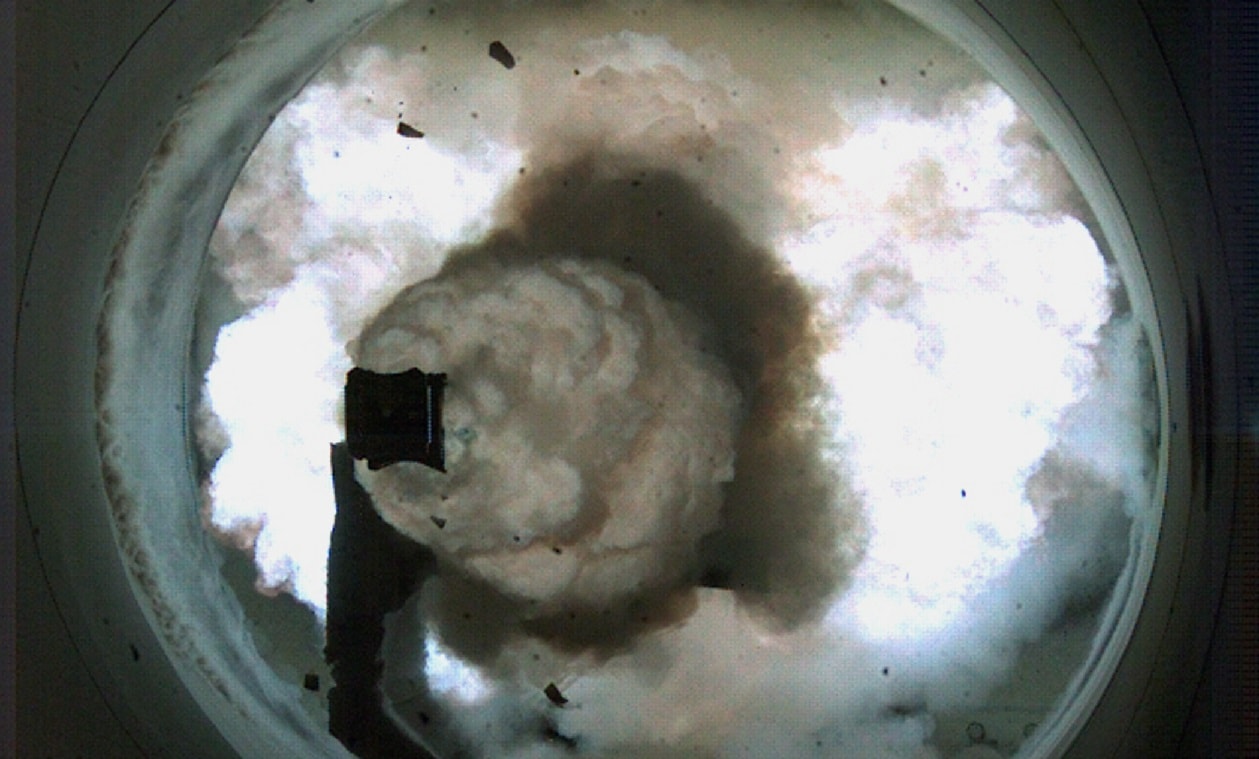

DAHLGREN, Va. (Dec. 10, 2010) High-speed camera image of the Office of Naval Research Electromagnetic Railgun located at the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division, firing a world-record setting 33 mega-joule shot, breaking the previous record established Jan. 31, 2008. The railgun is a long-range, high-energy gun launch system that uses electricity rather than gunpowder or rocket motors to launch projectiles capable of striking a target at a range of more than 200 nautical miles with Mach 7 velocity. A future tactical railgun will hit targets at ranges almost 20 times farther than conventional surface ship combat systems. (U.S. Navy photo/Released)

-The absence of railguns is framed as judgment, not decline: modern naval advantage comes from scalable, sustainment-ready systems-of-systems, hypersonic strike delivered by practical platforms, and resilient networks that can be fielded and kept working under pressure.

Why the U.S. Navy Walked Away From Railguns: Power, Heat, and Barrel Erosion Won

The United States Navy once promised to deploy railguns, weapons that sounded as if they had slipped out of the pages of a science fiction novel and were on their way to the decks of American warships. Hypersonic projectiles. Electromagnetic launch. Ranges that, in theory at least, blurred the line between shells and missiles. It all sounded too good to be true.

It was. Quietly and without ceremony, the railgun program faded from view as engineering reality caught up with conceptual ambition. Today, no railguns sit on American warships.

Against the backdrop of Japan’s “successful” railgun program, critics now whisper that this failure exposes something deeper, a loss of edge, perhaps even a fatal flaw in America’s defense-industrial base. The argument has an obvious appeal.

But it misreads what the railgun’s absence actually signifies. The lack of operational railguns does not point to decay. It is a reminder of the brutal reality that military power is built not on futuristic promise but on systems that can realistically be integrated, sustained, and trusted in the type of wars the United States is actually preparing to fight.

The Railgun Mirage

The appeal of the railgun was always easy to grasp. By replacing chemical propellants with electromagnetic force, it promised speed and reach without the price tag of missile inventories. In Navy concept briefs and Congressional reports, the system was often billed as capable of Mach-7-class velocities, with deep magazines and low cost per shot. For a fleet worried about adversaries launching large salvos of anti-ship weapons, the idea had real gravitational pull.

That promise collapsed under the heavy weight of engineering reality. Railguns demanded enormous electrical power in short bursts. This stressed shipboard generators and energy storage systems while simultaneously generating heat that existing cooling architectures struggled to dissipate. Accuracy at tactically meaningful ranges proved difficult to sustain. Most damaging of all, barrel erosion imposed punishing limits on service life, undercutting the rate of fire and operational availability.

Physics Is Not a Conspiracy

It is fashionable to describe the railgun’s demise as bureaucratic timidity or institutional sclerosis. That framing misses the point. The program ran into the limits of materials science and naval engineering, not a lack of will. The Navy pushed hard enough to discover where dreams ended and reality began.

In this context, failure is not a sign of decadence but of judgment. Militaries that cling to unworkable ideas tend to arrive on the battlefield with systems that look impressive on paper and disappoint in combat. The United States learned that railguns fell into that category and adjusted course accordingly. The railgun did not fail because it aimed too high, but because the platforms required to make it viable did not exist at scale.

Ships, Power, and the Zumwalt Problem

One detail matters more than most railgun commentary admits.

The weapon was never just a gun. It was a ship-design problem. Existing Arleigh Burke–class destroyers were never built to deliver the electrical power pulses the railgun required. Retrofitting them meant trading combat systems for energy capacity, an exchange no fleet commander would be eager to make.

210421-N-FC670-1062 PACIFIC OCEAN (April 21, 2021) Zumwalt-class guided-missile destroyer USS Michael Monsoor (DDG 1001) participates in U.S. Pacific Fleet’s Unmanned Systems Integrated Battle Problem (UxS IBP) 21, April 21. UxS IBP 21 integrates manned and unmanned capabilities into challenging operational scenarios to generate warfighting advantages. (U.S. Navy photo by Chief Mass Communication Specialist Shannon Renfroe)

SAN DIEGO (Dec. 8, 2016) The guided-missile destroyer USS Zumwalt (DDG 1000) arrives at its new homeport in San Diego. Zumwalt, the Navy’s most technologically advanced surface ship, will now begin installation of combat systems, testing and evaluation and operation integration with the fleet. (U.S. Navy photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Emiline L. M. Senn/Released)

161208-N-ZF498-130 .SAN DIEGO (Dec. 8, 2016) The U.S. Navy’s newest warship, USS Zumwalt (DDG 1000) passes Coronado bridge on its way to Naval Base San Diego. Zumwalt is the lead ship of a class of next-generation multi-mission destroyers, now homeported in San Diego. (U.S. Navy photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Anthony N. Hilkowski/Released)

The Zumwalt-class destroyers, with their integrated power systems, appeared to offer a solution. They could generate and route far more electrical power than earlier ships. Yet even there, the railgun struggled. Competing demands from sensors, computing, and future directed-energy systems narrowed the margin.

A weapon that worked on only a handful of specialized hulls ceased to look like a fleet solution and began to resemble a bespoke platform fix.

The railgun’s problem was not imagination. It was integration.

What Actually Replaced It

As the railgun faded, the Navy did not stand still. Investment flowed toward hypersonic anti-ship missiles, improved interceptors, and targeting networks that extend the reach of existing weapons. The emphasis shifted away from single revolutionary platforms toward systems that could be fielded, integrated, sustained, and scaled.

That shift reflects a bigger change in how naval combat is now understood. Modern naval engagements will be won by those who see first, share information rapidly, and can network fires across multiple platforms. In that battlespace, a system as formidable on paper as the proposed railgun brings negligible increase to fighting capability if it cannot be integrated dependably into the system-of-systems and sustained during the rigors of actual operations.

The railgun was conceived in an era still seduced by breakthrough hardware. The fleet that replaced it is built around systems-of-systems and resilience.

Hypersonics Without Rails

Arguably, the railgun’s most famous progeny, the hypersonic projectile, did not disappear with the program’s cancellation. Instead, it evolved. America still seeks hypersonic strike potential through delivery methods that sidestep the brute physics that doomed electromagnetic acceleration. Boost-glide weapons and air-launched platforms provide similar operational outcomes without barrel taxing or hogging electrical power.

From a strategic standpoint, this is the better trade. Hypersonic weapons deployed across submarines, aircraft, and mobile platforms impose uncertainty on adversaries that a handful of railgun-equipped surface ships never could. The objective was never the railgun itself. The objective was compressed decision time and credible long-range strike.

That objective remains intact.

The Real Constraint

Above all, the railgun story exposes the difficulty of turning ambitious concepts into systems that can be built, maintained, and replaced at scale. Supply chains, skilled labor, testing infrastructure, and production capacity matter more than conceptual ambition or design elegance.

Zumwalt-Class U.S. Navy Destroyer. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Railguns demanded bespoke solutions that resisted industrialization, and that failure is the more important lesson to draw. The real constraint exposed by the program was not imagination but the capacity to turn advanced concepts into systems that can be built, sustained, and replaced at scale. Prototypes do not win wars. They are won by weapons and platforms that can be produced in quantity and kept working under pressure.

No Fatal Flaw

History offers a colder lesson: that success in war is determined less by technical brilliance than by the practical use of available means. Power accrues to states that align technology with doctrine and logistics, and that possess the strategic discipline to forego systems that promise spectacle but are unlikely to deliver battlefield advantage.

The United States retains decisive advantages in undersea warfare, carrier aviation, global sustainment, and joint operations. Railguns were never central to that architecture. What would be dangerous is clinging to an unworkable system for the sake of appearances, or to satisfy political pressures tied to industrial interests rather than military necessity.

The railgun’s quiet disappearance is not an epitaph. It is evidence of a military that still knows how to say no to bad ideas, even when they arrive wrapped in the language of the future.

About the Author: Dr. Andrew Latham

Andrew Latham is a non-resident fellow at Defense Priorities and a professor of international relations and political theory at Macalester College in Saint Paul, MN. You can follow him on X: @aakatham.