With Iran resuming its enrichment of uranium, we asked Pres. Biden if the U.S. will lift sanctions first in order to get Iran back to the negotiating table on a nuclear deal.

“No,” Pres. Biden says, affirming that Iran will have to stop its enrichment program first pic.twitter.com/OPszf15Q1o

— Norah O’Donnell ???????? (@NorahODonnell) February 7, 2021

In his first discussion of the Iran nuclear deal since taking office, President Biden stepped on his toes. The question is whether it’s indicative of something amiss with the policy substance, or if he just misspoke. Or both.

In a brief exchange with Norah O’Donnell, the only discussion of Iran in their interview, this happened:

NORAH O’DONNELL (CBS EVENING NEWS): Will the U.S. lift sanctions first in order to get Iran back to the negotiating table?

PRESIDENT JOE BIDEN (CBS EVENING NEWS): No.

NORAH O’DONNELL (CBS EVENING NEWS): They have to stop enriching uranium first?

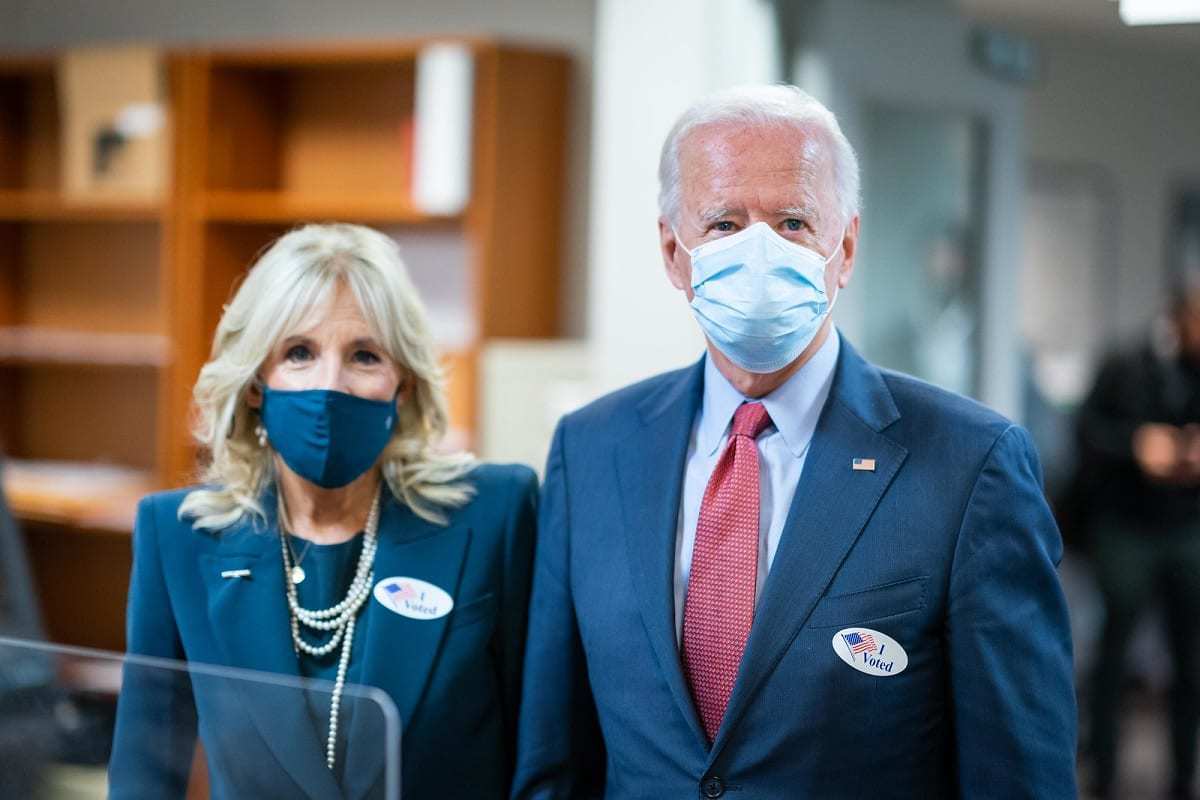

At that point Biden nodded, which you can see in O’Donnell’s tweet of the interview (see above).

This is worrisome, because zero enrichment was never part of the agreement and is exceedingly unlikely to be part of a resuscitated Iran deal. Iran watchers jumped on the statement, and an unnamed Biden official responded by walking back the remark, stating that Biden meant to say complying with the enrichment limitations embodied in the deal.

The broader worry here is that the Biden team seem to be taking their sweet time working out their Iran policy, and they may not have as much time as they think. Secretary of State Antony Blinken reportedly told Iran envoy Rob Malley to bring in some voices that are “more hawkish” on Iran. For his part, Malley told Axios just before being named Iran envoy that both sides have incentives to get a return buttoned up by the June presidential election in Iran, but that that election shouldn’t “act as a gun to the Biden administration’s head—that they need to reach a deal before then or otherwise they’re not going to reach one.”

In fairness to the Biden people, there was an awful lot going on behind the scenes to lay the groundwork for the negotiations that were to become the JCPOA, and there may be a lot that we’re not seeing here. But based on what we do see, there a couple of reasons for concern:

First, letting this run-up to, or through, the Iranian election may not have good results. A lot of thinking has Rouhani being replaced by a more hardline president no matter what happens with the nuclear deal. But letting nationalists make hay over the suffering from American sanctions and reneging on the deal seems unlikely to help anything. The fact remains that the IAEA confirmed Iranian compliance with the deal until the Trump administration left it in 2018. People in Iran could be forgiven for believing that the United States is inherently hostile and cannot be trusted. You don’t want to see that result in an Iranian election, notwithstanding the fact that the Supreme Leader is the ultimate decider, and obviously not elected.

Second, we may already be at the point that we’re running up to the Iranian election. Ernest Moniz, a nuclear expert who helped negotiate the deal under the Obama administration, guesstimated that it would take roughly four months, with conservative assumptions, to get Iran back into compliance. But given the likely rigamarole of “who does what first, then who does what in response, over what period…” and so on, this could take much longer.

Blinken—or somebody—should probably give a clear speech with some content about what they’re doing here. Right now, it’s hard to tell from outside.

Justin Logan is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute. He is an expert on U.S. grand strategy, international relations theory, and American foreign policy. His current research focuses on the shifting balance of power in Asia — specifically with regard to China — and the limited relevance of the Middle East to U.S. national security.