In the year since U.S. and Taliban negotiators signed an agreement in Doha to close out America’s 20-year long involvement in Afghanistan’s civil war, the intra-Afghan peace process has made very little progress—and the Biden administration is getting justifiably impatient. In an attempt to inject momentum into the floundering process, Secretary of State Antony Blinken wrote a strongly-worded letter to Afghan President Ashraf Ghani expressing his disapproval at the state of negotiations. U.S. special envoy Zalmay Khalilzad has gone as far as handing Kabul and the Taliban a draft peace agreement.

Washington is clearly embarking on a renewed diplomatic push to get the Taliban and the Afghan government back to the table. U.S. troops, however, should not be a part of the equation—and neither should they be used as leverage to extract a peace that may never come. All U.S. troops should be withdrawn from Afghanistan by May 1.

As the fighting on the ground persists in Afghanistan, U.S. policymakers in Washington are looking at three general options: 1) removing all U.S. forces by May 1, in line with the U.S.-Taliban agreement, 2) negotiate with the Taliban on a short-term extension, or 3) ignore the U.S.-Taliban agreement and keep U.S. troops in Afghanistan for the foreseeable future.

The second option, a short-term extension of the U.S. troop presence, is an appealing one for many in the U.S. foreign policy establishment. But it is also highly unlikely to be meaningfully successful. The Taliban today are in a highly advantageous position on the battlefield, with its fighters besieging multiple provincial capitals across the country and fighting Afghan security forces to the brink of exhaustion. The Taliban are looking to a post-U.S. Afghanistan, where they can continue to press its military campaign against Kabul—if not to overtake the entire country by force, then to increase its leverage in the event intra-Afghan negotiations resume.

The group has no incentive to work with Washington on a U.S. troop extension, a scenario totally contrary to its central organizing principle: the removal of all foreign forces. And even if the Taliban was willing to cooperate on such a scheme, it is difficult to see how giving the U.S. more time in Afghanistan would move the country closer to a state of peace. The systemic issues that have divided the Afghan government and the Taliban for two decades will persist regardless of how many U.S. troops are deployed on Afghan soil. Nobody proposing an extension has sufficiently explained how and why keeping U.S. forces in-country would mitigate those substantial political differences.

The third option, throwing the U.S.-Taliban deal aside, is so fraught with risks that the Biden administration should immediately eliminate it as a serious proposal. Senior Taliban officials have made it abundantly clear that failing to abide by the May 1 withdrawal deadline codified in the February 2020 agreement would result in a renewed military offensive against Americans. This is no idle threat; Taliban fighters have been preparing for just this eventuality. As controversial as the U.S.-Taliban deal was, no American has been killed by Taliban fire since it was signed. Ignoring the May 1 withdrawal date would surely break the streak, producing nothing more than additional casualties in a war that has already claimed the lives of over 2,300 U.S. servicemembers and sucked as much as $2 trillion from the U.S. Treasury.

The only responsible option for the United States is full-scale withdrawal by May 1. Critics contend that leaving Afghanistan would facilitate even worse violence in Afghanistan and put the U.S. homeland at risk of another large-scale, 9/11-style terrorist attack. These same critics, however, refuse to acknowledge just how capable the U.S. counterterrorism apparatus has become since 9/11, seen most clearly in the numerous kinetic strikes against high-profile terrorist leaders in countries from Iraq to Pakistan. They also fail to grasp what should have been obvious a decade ago: U.S. troops can’t resolve Afghanistan’s civil war for the Afghans, nor are they responsible for bailing out a besieged, corrupt, and parochial Afghan political elite most concerned with keeping themselves in power. Deeper and more sustained U.S. military involvement would enmesh the U.S. military into the sunk-cost fallacy, where more money and lives are expended in order to justify past investment.

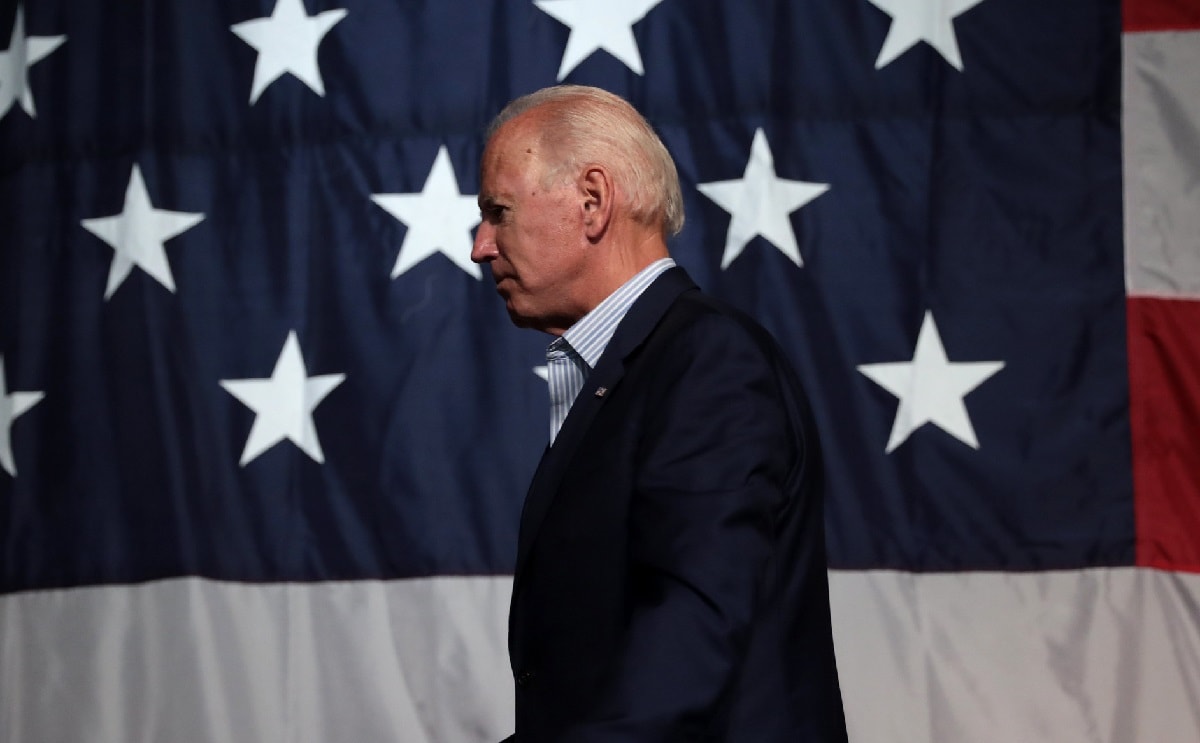

As vice president, Joe Biden never bought into the fallacy that U.S. troops could turn Afghanistan into a beacon of peace and liberty. More than a decade after he strongly opposed sending an additional 30,000 U.S. forces into Afghanistan, now-President Biden has the opportunity to do what his predecessors should have—accept the grim reality of the situation, recognize that the U.S. doesn’t need to be in Afghanistan to defend the U.S. from terrorism, and put an end to the longest war in U.S. history.

Daniel R. DePetris is a fellow at Defense Priorities and a foreign affairs columnist at Newsweek.