The SR-71 Blackbird, a Cold War workhorse that flew at record speeds, was the top dog in reconnaissance airplanes from its inception in the 1960s until its retirement in 1999. Engineers can still learn a lot from the SR-71, which was supreme in the skies during its reign. The bird was maintenance-heavy and expensive to fly leading to its eventual mothballing, but it was still an engineering marvel and ahead of its time.

Russian air defenses got better and that hastened the SR-71’s decline. Also, the growth of strategic drones, such as the U.S. Global Hawk, new enemy surface to air missiles, spy satellites, and advanced Russian fighters made the Blackbird expendable.

But what an airplane.

Able to reach speeds of MACH 3.2 for 90 minutes, it is still considered the fastest aircraft in U.S. history and has the record for the highest altitude at 85,000 feet.

What Made the SR-71 Unique?

The product of a super-secret project from Lockheed’s uber-successful Skunk Works in the Nevada desert, it could outfly the old Soviet SAMs and travel at the edge of space. The design was extremely innovative. The black paint dispersed heat and lowered the temperature. The fuselage and windshield heated up to 600 degrees Fahrenheit. Meanwhile, the long fuselage could bend while the wings curved and twisted in flight to improve the aerodynamics. The SR-71 increased its size to four-inches during flight. The airplane was made of titanium, then considered a whiz-bang material.

But it cost an estimated $200,000 an hour to fly. The fuel was difficult to ignite and so the SR-71 had to invent a new chemical ignition system for the engines. Advanced side-looking radar and two cameras did the spying. The SR-71 could also snoop for electronic signals from the Soviets. It had a smaller radar cross-section that made observability lower and the iron ferrite paint absorbed radar signals. Moreover, it had excellent electronic countermeasures.

What Modern Engineers Can Learn from the SR-71

Looking back to the early development of the airplane, history can provide many lessons learned. It is possible to create something that required numerous new inventions. Thinking outside the box is a cliché nowadays, but the Skunk Works designers were fearless when it came to pushing out innovative solutions to flight problems. The engineers originally had only 20 months to develop the first A-12 prototype – the precursor to the SR-71.

Manufacturers had to learn about titanium on the fly. The metal was brittle and could shatter on the assembly line. So, they had to invent new tools – also out of titanium. Piloting the plane was an art. According to an SR-71 history from Lockheed Martin, one pilot was astounded during flights. “At 85,000 feet and Mach 3, it was almost a religious experience,” said Air Force Colonel Jim Wadkins. “Nothing had prepared me to fly that fast… My God, even now, I get goosebumps remembering.”

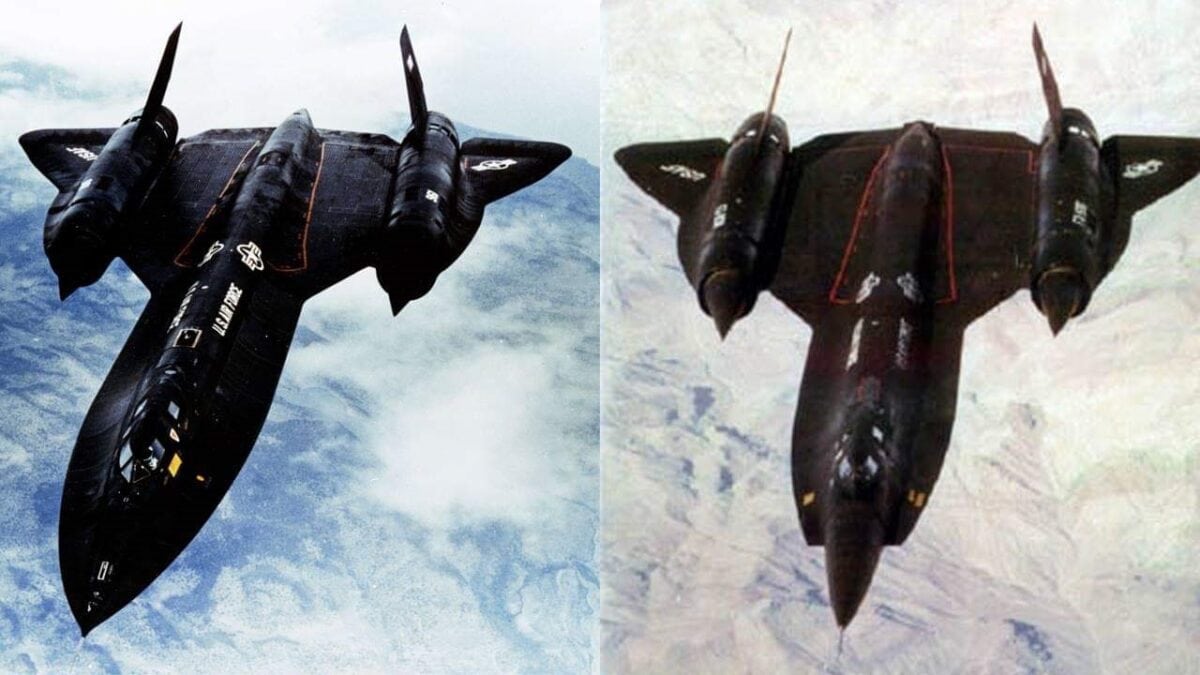

SR-71. Image: Creative Commons.

SR-71 and A-12 side by side for comparison.

1945’s new Defense and National Security Editor, Brent M. Eastwood, PhD, is the author of Humans, Machines, and Data: Future Trends in Warfare. He is an Emerging Threats expert and former U.S. Army Infantry officer.