Those 85 days saw some of the worst fighting of the war. It was an inch by inch, foot by foot, yard by yard hard slog through thick mud, oozing slime, deep water in virtually continuous rain against fierce, concentrated enemy fire. – Graham Thomas,“Attack on the Scheldt: The Struggle for Antwerp 1944”

On September 4, 1944, the cheering crowds that greeted the tanks of the British 11th Armored Division seemed to mark a war-winning moment.

The Belgian port of Antwerp had been captured intact.

For the Allied armies that had broken out of the Normandy bridgehead in August and surged 500 miles to the German border, the biggest enemy wasn’t the broken German armies fleeing back to the Reich. The real foe was logistics. With French and Belgian ports either demolished or stubbornly defended by sacrificial German garrisons, and the French rail network devastated by Allied bombers, supplies – especially gasoline – had to be hauled 500 miles from Normandy to Germany by a far too small fleet of trucks.

Antwerp was the second-largest port in Europe, with ample capacity to sustain the Allied drive into the heart of Germany. By all expectations, Antwerp should have been a wasteland, its docks and wharves blown up by Hitler’s armies as they had done during their retreat from France and Russia in 1943-44. Deprived of supplies, the Allies would have to pause their advance, offering the Nazis precious time to regroup their armies and field new wonder weapons.

In the chaos of retreat, the Germans had failed to demolish Antwerp. Yet consumed by victory fever, and tempted by the prospect of ending the war with a quick thrust across the Rhine and toward Berlin, British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery made a crucial decision. Instead of securing Antwerp, Montgomery’s 21st Army Group would launch Operation Market-Garden, an airborne and armored assault to seize a series of bridges and “bounce” the Rhine before the Germans could regroup.

But even Montgomery – never one to admit a mistake – later conceded his error. Market-Garden failed, leading to the destruction of a British airborne division at the infamous “bridge too far” at Arnhem. Meanwhile, 90,000 men of the German Fifteenth Army had escaped to the Scheldt Estuary.

The stage was set for the Battle of the Scheldt.

The Breskens Pocket

Had 11th Armored Division pushed on immediately into the South Beveland Peninsula, which it had the petrol to do, Walcheren might have fallen two months sooner, with far fewer casualties,” Richard Brooks, “Walcheren 1944: Storming Hitler’s Island Fortress.”

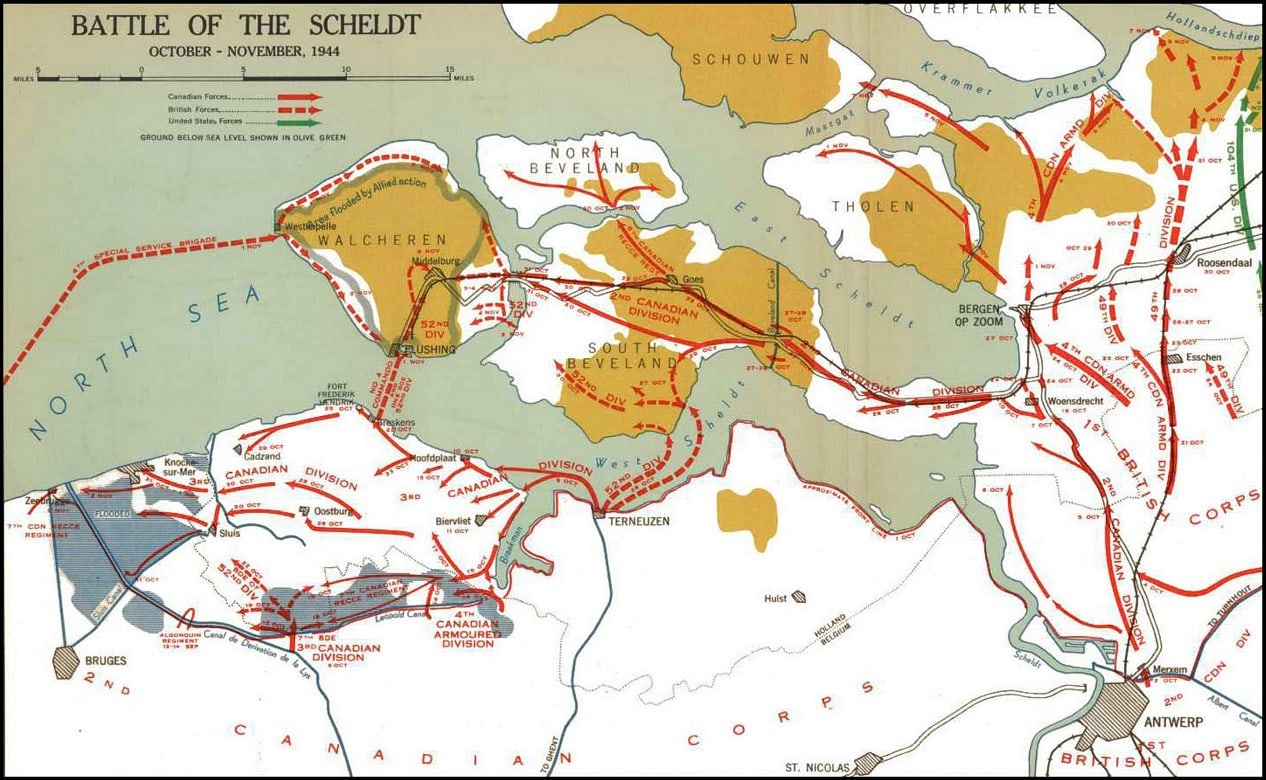

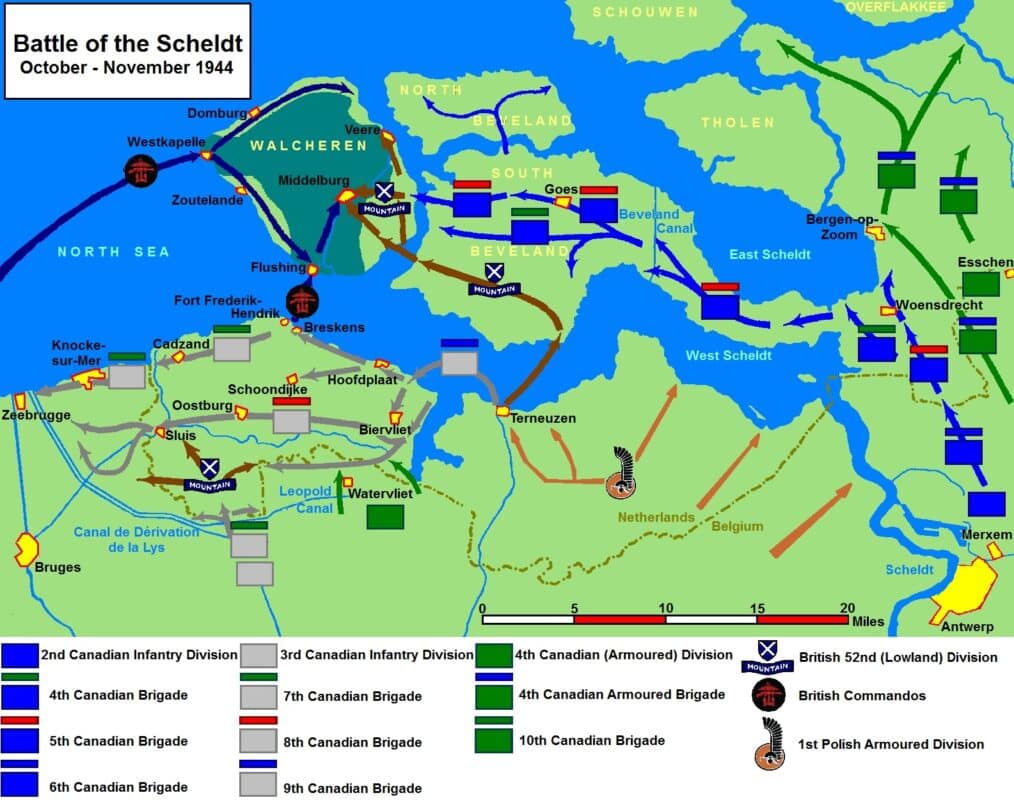

Battle of the Scheldt Map. Image Credit: Michael Dorosh/Canadiansoldiers.com

Antwerp has a strategic vulnerability: as an inland port, ships arriving from the North Sea must steam 70 miles east through the Scheldt Estuary – mostly through Dutch territory — before they turned south to dock in Antwerp. The mouth of the Scheldt forms a natural chokepoint: on the northern side is the Dutch island of Walcheren, and on the southern (mainland) side is the South Breskens region. The Germans didn’t need to occupy Antwerp to render the port useless. Coastal artillery on the banks of the Scheldt could sink any cargo ships sailing through the estuary, as well as destroying any minesweepers that tried to clear the hundreds of underwater mines the Germans had laid.

However, the German troops defending the Scheldt were a sorry lot. There were a few good units such as paratroopers, but mostly they consisted of whatever the Wehrmacht would throw together at the end of the war, including sailors fighting on land, “stomach” battalions of soldiers whose gastric ailments required a special diet of white bread. Nonetheless, dislodging them would be a nightmare. In the rainy autumn of 1944, the flat Dutch polder – low-lying land reclaimed by the Dutch from the sea – was flooded, muddy and slashed by canals and ditches (made even wetter after the Germans deliberately flooded the area). Off-road movement was a slog for infantry and almost impossible for vehicles, which meant movement tended to be confined to a few raised roadways that the Germans could easily defend.

Walcheren, a large 83-square-mile island, would be even tougher. “Walcheren is often described as a saucer, or a soup plate with a chipped rim consisting of high dunes of loose soft sand,” noted Brooks. “Infantry might scramble up these, but not vehicles.”

The First Canadian Army drew the unenviable task of ejecting the Germans and securing the Scheldt. The Northwest Europe campaign had not been easy for the Canadian Army: there were manpower shortages caused by a reluctance to send conscripts rather than volunteers outside Canada, as well as Montgomery’s dislike of First Canadian Army commander Harry Crerar (conversely, some Canadian and other Commonwealth contingents complained that the British regarded them as cannon fodder). At first glance, the 135,000-strong First Canadian Army – assisted by the British 52nd Infantry Division and British flamethrower tanks – appeared a formidable force, especially given its vast superiority over the Germans in armor, artillery, and air support. But bad weather and flat, coverless and mine-strewn terrain would nullify many of the Allied advantages.

To make matters worse, the Allies had to wage four separate battles: clearing the German forces to the north of Antwerp and isolating Walcheren and South Beveland, eliminating the Breskens Pocket of German defenders blocking access to the southern Scheldt, capturing the South Beveland peninsula jutting into the Scheldt north of Antwerp, and finally storming Walcheren Island. It would have been a tough enough fight for a rested, full-strength army in warm summer weather, let alone a cold, wet autumn. Nor would it be picnic for the Germans, who also had to scramble to stay on dry land, especially if Allied bombers breached the dykes keeping the North Sea at bay.

The first phase of the operation was a taste of things to come. Operation Switchback began in early October, a two-pronged advance from east and west of the Breskens Pocket to cross the Leopold Canal and clear the south bank of the Scheldt. Assisted by American-made Buffalo LVT (Landing Vehicle Tracked) armored amphibious troop carriers and Wasp flame-throwing armored vehicles – which induced many Germans to surrender rather than face incineration in their bunkers – the Canadians managed to secure bridgeheads in the face of German counterattacks. The Canadian 7th Brigade alone suffered 553 casualties.

Stung by criticism from other Allied commanders, Montgomery belatedly realized his mistake and ordered that clearing the Scheldt would have top priority. By the end of October, the south bank of the Scheldt had been cleared. South Beveland was captured next, after Buffalo amphibious tractors supported an assault across a canal bisecting an isthmus covered by German fire.

Now came the hardest part.

Assault on Walcheren

Could as grim a battle as the Scheldt end on other than a painful and bloody note? Capturing the final German bastion on Walcheren by land meant assaulting across a narrow, heavily defended causeway.

The solution: a miniature D-Day. Just as the Germans had used the sea to stymie their attackers, so the Allies would use the sea to outflank the Germans. Operation Infatuate called for landing the elite 4th Special Service Brigade of commandos and the 52nd Lowland Division, a Scottish unit trained in mountain warfare and air landing operations behind enemy lines (naturally, the 52nd was assigned to an amphibious invasion it had never trained for). The infantry would be assisted by British “funny” tanks that would clear minefields and knock out fortifications.

To transport this force, the Royal Navy assembled a small armada of 182 vessels, including numerous landing craft and gunboats backed by heavy warships such as the battleship HMS Warspite and the monitors HMS Erebus and Roberts, armed with 15-inch guns that could hurl one-ton shells. Unlike the Normandy invasion, the assault troops would count on land-based artillery: 300 guns on the mainland, as well as Typhoon fighter-bombers.

All that firepower would be desperately needed. There were as many as 10,000 German on Walcheren, with plenty of coastal artillery embedded in concrete bunkers. But the German defense had to be an all-or-nothing effort on the beaches: the Allies had bombed the dykes on Walcheren, flooding the interior of the island so the defenders couldn’t retreat.

On November 1, 1944, Allied troops landed at Vlissingen, on the southwest on Walcheren, followed that same day by a descent on Westkappelle on the western side. Despite losses from coastal defenses – including a brave gunboat flotilla that lost 13 out of 27 vessels at Westkappelle – the landings succeeded. Fighting would continue for another week, including house-to-house fighting in Vlissingen and an assault by 2nd Canadian Division across the causeway from South Beveland. But on November 8, 1944, the Germans on Walcheren surrendered.

Even before Walcheren surrendered, a force of nearly 200 minesweepers and support craft had already begun clearing the Scheldt of mines in an operation that would take almost a month to clear 267 mines. On November 28, 1944, the first of many cargo ships sailed up the Scheldt Estuary and docked in Antwerp. In April 1945 alone, the port would handle 1.7 million tons of cargo that would comprise the bulk of Allied logistics in Northwest Europe.

The Scheldt was a battle that should never have been necessary. Nor did it have the high drama of an epic struggle like Stalingrad or the Battle of the Bulge. But the battle did not deserve to be neglected, either. The Allies had suffered almost 13,000 casualties in the Battle of the Scheldt – the majority Canadian – while the Germans suffered about 12,000, plus 41,000 taken prisoner. And though neglected in military histories of the battle, numerous Dutch civilians were killed and wounded in the crossfire, or suffered starvation and flooding. Some 87 percent of Walcheren was flooded, and the island was strewn with mines that would continue to kill long after the battle.

Nonetheless, Antwerp was a prize worth almost any sacrifice: the Battle of the Bulge, for example, might have been a German victory if the hard-pressed American armies had not been able to draw supplies from nearby Antwerp. Victory at the Scheldt did much to hasten the end of the Third Reich and victory in Europe.

A seasoned defense and national security writer and expert, Michael Peck is a contributing writer for Forbes Magazine. His work has appeared in Foreign Policy Magazine, Defense News, The National Interest, and other publications. He can be found on Twitter and Linkedin.