Is America vulnerable to another Battle of the Bulge today?

It was 77 years ago when the U.S. nearly suffered its greatest military disaster. On December 16, 1944, a massive German surprise offensive slammed into weak American forces defending the Ardennes region of Belgium.

For a few terrifying days, it seemed as Hitler’s panzer divisions might achieve a breakthrough that might not have saved the Third Reich, but could have prolonged the war. That Operation Watch am Rhein (Watch on the Rhine) ultimately failed was due to myriad reasons: a flawed and overambitious German plan, rough terrain that favored the defender, the depleted state of the Nazi war machine in late 1944, and superior U.S. artillery, airpower and logistics. And most important of all, the bravery of American troops who – despite some early battlefield lapses – fought stubbornly to delay and ultimately repel the German offensive.

Could America face a battle like the Bulge again?

In the purely military sense, the answer is no. The Germans deployed 200,000 troops and 600 tanks for the offensive, and that was just a fraction of the German army, the bulk of which was desperately fighting on the Eastern Front to stave off the Red Army. They faced 84,000 U.S. troops, which grew to 700,000 American and British soldiers by the end of the battle in mid-January.

Such mass armies may have been common in both World Wars and the Cold War, but they have faded away. Soldiers and weapons have become too expensive, conscription has largely been abolished, and even China is downsizing its military. Nor would such a concentration of troops pass unnoticed in an age of spy satellites, cell phone videos, and social media: Russia’s recent deployment of 100,000 troops on Ukraine’s border has been amply and ceaselessly documented by military and civilian observers.

But this is just numbers and technology, all of which are important — and none of which are the real lessons of the Bulge.

Failures of Intelligence and Imagination

The Battle of the Bulge is often cited as an example of an intelligence failure. How much advance warning Allied intelligence had of the German offensive is still controversial, but there were signs from the usual sources – decrypted radio messages, aerial reconnaissance, prisoner interrogations – that were inevitable with an offensive of that magnitude. However, Allied intelligence dismissed the warning indicators. The Third Reich was on its last legs, and Hitler couldn’t possibly be crazy enough to squander his last reserves on an attack that could leave Germany defenseless against the invading Allied and Soviet armies.

“This optimism, particularly when heightened by reports that the enemy no longer had fuel for tanks and planes, conditioned all estimates of the enemy’s plans and capabilities,” notes the U.S. Army’s official history of the Bulge. “It may be phrased this way: the enemy can still do something but he can’t do much; he lacks the men, the planes, the tanks, the fuel, and the ammunition.”

In other words, there was a failure of imagination. Or perhaps a failure to appreciate that the enemy has an imagination that would let them do the unexpected, just like the Tet Offensive and 9/11.

‘Cobra King’ on Rose Barracks in Vilseck, Germany, today. During the Battle of the Bulge, the tank and its crew led an armor and infantry column that relieved the 101st Airborne Division at Bastogne.

Compared to World War II, the U.S. enjoys an incredibly sophisticated array of technical means for collecting intelligence, from spy satellites to surveillance drones and NSA codebreakers. There is a very good chance that Chinese preparations to invade Taiwan, or Russian preparations to invade Ukraine or the Baltic States, would be detected days or weeks in advance. Yet ultimately, early warning won’t do much good unless it is accompanied by solid analysis – and prompt action to make use of intelligence.

Overstretch and Calculated Risk

Allied commander Gen. Dwight Eisenhower was better at managing a coalition army than as a military strategist. But Eisenhower didn’t leave the Ardennes weakly defended because he was stupid or negligent. To cover a 400-mile front from the North Sea to Switzerland, he had 96 divisions, which didn’t leave many to concentrate for attack or keep in the rear as a reserve. It was a calculated risk, and arguably a reasonable one – that almost resulted in disaster.

The U.S. military faces a similar situation today. It must prepare for a conflict with China that would mostly be a naval and air war, a conflict with Russia that would primarily be a ground and air war, and other missions such as counter-terrorism, peacekeeping and all the other duties that a global superpower demands of its armed forces.

The result is a U.S. Navy that is overworked, an Air Force that is worn out, and a U.S. Army that was overstretched by simultaneous wars in Afghanistan and Iraq while maintaining garrisons in Europe, Korea, and elsewhere. Even if Army units are available in the U.S. for deployment overseas, just finding enough railroad cars, cargo ships and transport planes to get them to Europe or Asia would be a problem.

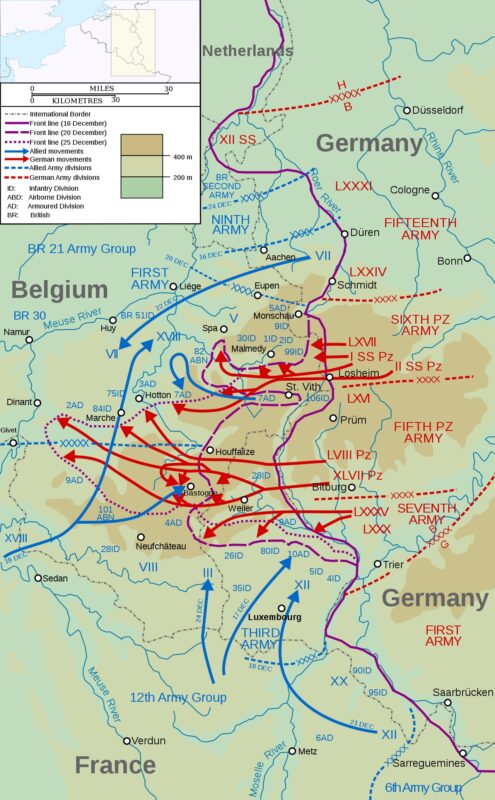

Map showing the swelling of “the Bulge” as the German offensive progressed creating the nose-like salient during 16–25 December 1944.

Increasing the size of the U.S. military would burden the U.S. economy and create recruitment and equipment problems, which means the U.S. is going to have to take a calculated risk in what type of forces to buy, and where to deploy them. Choosing poorly could have catastrophic consequence.

The Value of Coalitions

The German plan for the Ardennes Offensive was to essentially attack the middle part of the Allied lines – as they had successfully done to the French in 1940 – and split the American and British armies in two. Hitler was also convinced that the coalition between America, Britain and the Soviet Union, was an unnatural one that would fall apart.

But in 1944, the Grand Alliance held. British troops north of the Ardennes quickly moved to block any German penetration toward the vital port of Antwerp, while British commander Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery took over command of U.S. forces in the north of the Bulge. Though British troops didn’t do much fighting at the Bulge – and Montgomery was accused of taking credit for “tidying up” a battle mostly won by American soldiers – having a coalition partner to back up U.S. forces was invaluable. And whatever the later animosity of the Cold War, the Soviet Union fought 75 percent of the German army during World War II, which saved the lives of a lot of U.S. soldiers.

Today, America still has coalition partners in NATO, and allies such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Israel. While those ties have frayed in recent years, alliances still give the U.S. an enormous military, political and economic advantage against China and Russia, who have made few allies while antagonizing many of their neighbors.

Can America experience another Battle of the Bulge? No, there won’t be battalions of German tanks emerging from the winter mists. But yes, similar surprises can happen.

A seasoned defense and national security writer and expert, Michael Peck is a contributing writer for Forbes Magazine. His work has appeared in Foreign Policy Magazine, Defense News, The National Interest, and other publications. He can be found on Twitter and Linkedin.