W.B. Yeats once wrote that “the centre cannot hold.” In Canada’s case, this is increasingly true.

The Slow Dissolving of Canada

The country isn’t collapsing under the weight of competing separatist projects. Rather, it’s quietly dissolving under the acids of institutional unraveling, political incoherence, and a growing sense that regional interests and identities are more important than any sense of “Canadianness.” The problem, therefore, is not one of a dramatic crisis. It’s more one of incremental balkanization. Provinces aren’t formally breaking away from the Canadian confederation. Rather, they’re just increasingly doing their own thing – irrespective of Ottawa and the national vision that that city represents.

What’s emerging is a federation in name only. Provincial governments across the country are increasingly asserting autonomy on major policy files without federal coordination or even acknowledgment. This is not rhetorical separatism or symbolic posturing. It’s administrative sovereignty by default. And it is happening in real time.

Alberta offers the most direct example. The Alberta Sovereignty Within a United Canada Act was originally dismissed by national commentators as a political stunt. It isn’t. The Conservative government of Danielle Smith has used it to reject or sidestep federal regulations on firearms, natural resources, and climate assessments. The province is effectively testing the boundaries of Canadian federalism—and finding little resistance.

This isn’t secessionist theater. It’s the operationalization of a political worldview: that Ottawa no longer adds value. Alberta’s leadership is behaving as if the province’s future will be determined in Edmonton, not in the capital. Public opinion reflects this posture. Consistent polling puts support for Alberta independence between 35 and 45 percent—not as a protest, but as a fallback position. The sentiment is not driven by rage, but by a growing perception that the federation is misaligned with Alberta’s interests.

In Quebec, the politics are older but follow a parallel logic. The Parti Québécois, under Paul St-Pierre Plamondon, has promised to hold a third referendum on sovereignty by 2030 if elected. The PQ currently holds only four seats in the National Assembly, so the pledge is more strategic than imminent. But it reflects the continued normalization of Quebec’s autonomy.

Polling shows support for independence has dropped to 29%, down from 37% just three months prior. That decline should not be misread. It indicates that Quebecers are less interested in formal rupture, not that they are satisfied federalists. The province continues to pursue unilateral authority over immigration, cultural policy, pensions, and education. Federal programs are often refused outright or reshaped beyond recognition. The underlying message: sovereignty is already here in practice, if not in name.

British Columbia is disengaging in a different direction. It has no sovereigntist movement, but it increasingly acts like a Pacific substate rather than a Canadian province. On issues like trade, green energy, and migration, B.C. is more interested in the Indo-Pacific than in interprovincial consensus. Its relationship with Ottawa is not confrontational—it’s irrelevant.

Saskatchewan has aligned closely with Alberta on jurisdictional assertiveness. Newfoundland and Labrador continue to express frustration over equalization and offshore development. Even Ontario, historically the federation’s anchor, now governs with little regard for national cohesion. Doug Ford’s approach to federal-provincial relations is transactional, not collaborative.

What connects all of this is a basic breakdown in the logic of Canadian federalism. The country has not found a compelling reason to cohere. The institutions still function, but the political center no longer sets the terms. Ottawa is losing relevance not through conflict, but through political redundancy.

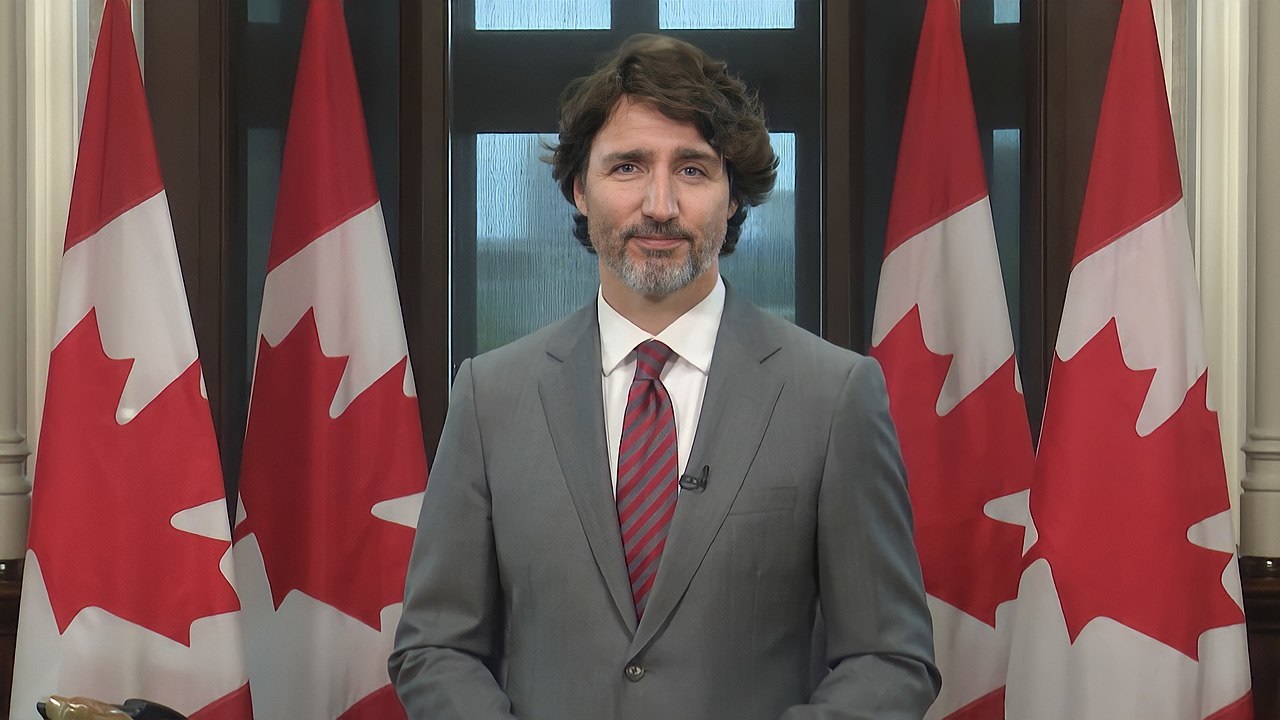

Much of this unraveling began during the Justin Trudeau era. His government leaned heavily on symbolic politics and over-promised on national unity through progressive messaging rather than serious governance. Federalism was treated more as a stage than a structure. The Justin Trudeau government left its successor a federation that still functions legally, but is increasingly incoherent in practice.

The new government, while more policy-focused, has inherited a system already in motion. Provinces aren’t waiting to be told what to do. They’re not even pretending to coordinate. They legislate independently. They challenge jurisdictional boundaries. They pursue external partnerships. The assumption that the federal government speaks for the country is no longer operative in most of the country.

This is no longer a domestic issue alone. The return of Donald Trump to the White House has underscored just how unmoored Canadian federalism has become. The Trump administration is increasingly willing to engage directly with Canadian provinces. Alberta is being approached on energy infrastructure. Quebec is being treated as a distinct actor on culture and climate. Washington is not undermining Ottawa; it is adjusting to the new reality. The provinces are where action happens. The federal government is where action slows down.

That shift is important. Once foreign powers begin treating subnational actors as sovereign in function, the formal cohesion of a country becomes less and less relevant. Canada still has a national government, a central bank, and a military. But these are administrative organs, not instruments of unity.

President Donald Trump’s meeting with Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau this week covered a host of topics: the need for swift passage of USMCA, solutions to the opioid crisis affecting both nations, defending human rights in the Western Hemisphere, and more

In previous moments of disunity, Canada at least tried to course correct. The Meech Lake Accord, the Charlottetown Accord, and the Clarity Act were all flawed but serious attempts to reestablish a national consensus. No such project exists today. There is no serious conversation about federal reform. No national strategy. No compelling vision. Just entropy.

The federation is now sustained by habit, transfers, and legal convention. That may be enough to preserve the surface. But it is not enough to restore coherence. And in a world where geopolitical pressure is rising and institutional efficiency matters more than ever, that is not sustainable.

The Fall of Canada

Canada is not disintegrating. It is unraveling. But the effect is the same. The provinces are no longer listening for the center. And the center is no longer capable of drawing them back. Yeats’s line still holds: the falcon cannot hear the falconer. Not because of rebellion. But because the call has grown too faint to matter.

About the Author: Andrew Latham

Andrew Latham is a non-resident fellow at Defense Priorities and a professor of international relations and political theory at Macalester College in Saint Paul, MN. Andrew is now a Contributing Editor to 19FortyFive, where he writes a daily column. You can follow him on X: @aakatham.