Last week’s missive forecast rough continuity in U.S. foreign policy following this month’s changeover of presidencies. After reading it a correspondent wants to know whether Communist China’s “involvement” in the Western Hemisphere might prompt political leaders in Washington DC to invoke the Monroe Doctrine to curtail such involvement. Such a move is not impossible; it is doubtful. The doctrine was a unilateral foreign-policy statement used to justify repeated armed intervention in the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico a century ago. These episodes are seared into Latin American historical memory. If it’s wise the new U.S. administration will fashion a doctrine of its own to cope with the China challenge.

Washington should try to manage that challenge free of baggage from bygone times.

That there’s a problem in the making verges on incontestable. Chinese inroads in the region are real and growing. To list one example among many, the Asian titan is Pacific power Chile’s largest trading partner. The exigencies of national development mean that Santiago cannot neglect the China factor when mulling foreign policy. Nor is Chile alone in this. Indeed, China has expanded its trade with Latin America as a whole by eighteenfold since the turn of the century. Chinese firms now own or operate such critical infrastructure as seaports, oilfields, telecommunications, and electrical grids. It’s the pattern typical of China’s “Belt and Road” economic diplomacy toward Eurasian countries, transplanted to the Americas: hook foreign governments and societies on Chinese largesse and you can demand concessions in a variety of areas.

Just as in Eurasia, then, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) prelates covet political say-so in the Americas as much as they covet economic gain. As U.S. Army War College professor Evan Ellis writes, Beijing’s agenda goes far beyond trade and commerce. In fact, there are no routine, apolitical commercial dealings with China. Politics suffuses everything. With commercial influence comes political and perhaps even military influence—a fact not lost on officialdom in Beijing. That’s why Chinese law compels all Chinese companies to abide by the leadership’s wishes—making them all implements of Chinese foreign policy. Even ostensibly private industry is an implement of Chinese Communist statecraft and thus a potential weapon.

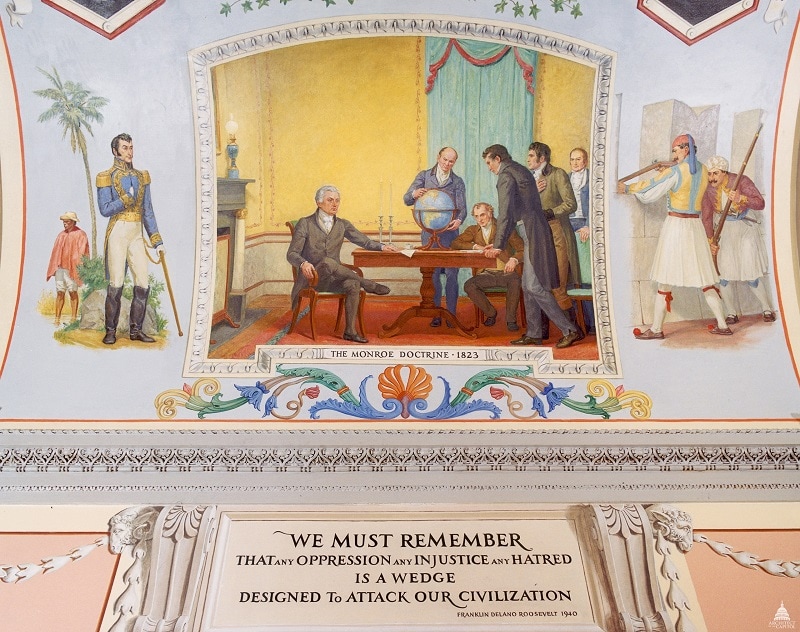

Allyn Cox Oil on Canvas 1973-1974 Great Experiment Hall Cox Corridors Responding to Russian territorial claims along the northern Pacific coast, and concerned that European nations would attempt to seize recently independent Latin American states, President James Monroe announced a new national policy. No new colonies would be allowed in the Americas, and European powers were not to interfere in the affairs of the Western Hemisphere. This mural depicts a discussion among the president and members of his cabinet; from left to right are President James Monroe, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, Attorney General William Wirt, Secretary of War John Calhoun, and Secretary of the Navy Samuel L. Southard. Left: Simón Bolívar, who fought for the independence of many Spanish colonies in South America, represents a commitment to liberty. Right: Greek freedom fighters, who were aided by Russia, Britain, and France in gaining autonomy from the Ottoman Empire, symbolize the struggle for freedom around the globe.

To what end? Chinese leaders crave a veto over Latin American decision-making. They want Latin American “workers and governing elites subservient to Chinese interests,” according to Ellis, with “political relations with Washington tolerated only so far as they do not conflict with Beijing’s interests.” If they get their way the United States may remain the security partner of choice for many if not most Latin American governments, but its relationships with them will become increasingly one-dimensional and brittle. Forced to choose between security cooperation with the United States and their own economic well-being, Latin American leaders might choose prosperity—and thus China. And Xi Jinping will smile.

What Ellis says squares with what I hear from friends and correspondents in the region.

What to do? While it’s doubtful Washington will cite the Monroe Doctrine by name to justify any countermoves vis-à-vis China, reviewing what the doctrine was and was not nonetheless hands observers an instrument useful for gauging how action/reaction dynamics might play out among China, Latin American states, and the United States. First of all, there was no single, static Monroe Doctrine. Like most foreign-policy precepts of long-standing, it underwent many phases as geopolitical circumstances changed around the United States, and the republic built itself into a great power of note—giving Washington the option to undertake more forceful hemispheric diplomacy.

The Monroe Doctrine started off simple and straightforward. By the letter of James Monroe’s and John Quincy Adams’s declaration, the U.S. leadership merely forbade European empires to reassert dominion over Latin American republics that had won their independence. In other words, it ruled the Western Hemisphere off-limits to fresh colonialism. That was it. The doctrine took on interventionist overtones toward the turn of the century. In the 1890s U.S. leaders briefly proclaimed that the United States was “practically sovereign” over the Western Hemisphere, meaning it reserved the right to make the rules in whatever matters Washington deemed important. The leadership backed off from this claim in the first decade of the new century, only to intervene promiscuously in the Caribbean basin—often by force of arms—in succeeding decades. For better and sometimes for worse, the doctrine underwent periodic reinterpretation.

So when judging Washington’s policies today astute observers won’t ask whether U.S. leaders are reviving the Monroe Doctrine. They should ask which Monroe Doctrine U.S. policy resembles most. And if the answer is that Joe Biden’s Washington has struck out on an entirely new course, that’s valuable insight in itself. Monroe and Adams will have rendered good service from beyond the grave.

Second, the Monroe Doctrine was chiefly about territory. U.S. political leaders and strategists fretted that European great powers might seize Latin American territory and construct naval or military bases there. From these bases ships of war could menace sea routes crucial to U.S. trade and diplomatic aspirations. The doctrine was never a blanket ban on European involvement in Latin America. Nor, if the pattern held today, would ordinary commercial relations between China and Latin America conjure up the ghosts of Monroe and Adams in Washington. But again, everything is political for Communist China. If Beijing tried to parley economic leverage into de facto sovereign control of a strategically placed seaport (and potential naval base)—as it arguably did in Sri Lanka—it could well trip the United States’ anti-interventionist reflex. History would rhyme.

U.S. policy could come to look mighty Monroeist while going by another name.

Third, not all European empires were the same for executors of the Monroe Doctrine. Again, the degree of threat was central—and that meant an extraregional threat to wrest ground from Latin American sovereigns. Because the doctrine was a unilateral policy, leaders in Washington reserved the right to choose when to invoke it and when to remain silent about European entanglements in Latin America. In sporting parlance they could declare, in effect: no harm, no foul. For instance, U.S. leaders evinced little concern about any French designs on Caribbean real estate. France posed no threat to the Americas. Nor did they concern themselves with Spanish imperialism after 1898, when U.S. sea and ground forces expelled the Spanish from their Caribbean island empire. They did worry, at least in theory, about Britain’s Royal Navy while gazing anxiously at the German High Seas Fleet that took shape starting around the turn of the century.

The latter were threats of serious heft. How U.S. officials react to Beijing’s Latin America diplomacy will indicate whether they regard China as a threat on par with imperial Germany or Great Britain, whether they consider it a France or Spain, or whether it poses some other type of challenge altogether. For instance, they might view China as a challenger on the order of the Soviet Union, a peer antagonist that courted military ties with Cuba in the 1960s.

And fourth, in the late 1920s the U.S. government distanced itself from the interventionist elements that had come to encrust the Monroe Doctrine. It eventually went further, foreswearing the right of forcible intervention altogether and codifying its pledge of forbearance by treaty. By the late 1930s, moreover, a series of inter-American conferences more or less regionalized the doctrine’s hands-off principle, putting such potential Old World aggressors as Nazi Germany on notice that the New World would stand together against martial incursions. From then on the doctrine cast a smaller and smaller shadow across Washington’s diplomatic and strategic calculus. Nowadays few policymakers or strategists mention it by name.

Still less do they appeal to it as a warrant for unilateral actions.

But if Latin American governments come to side with an overbearing China, it will become obvious that circumstances have corroded the inter-American ideal. Washington might resort to a more unilateral foreign-policy doctrine if the problem appears dire. If U.S. foreign-policy overseers conclude that China’s economic diplomacy poses a military threat, Monroeism could make a comeback—even if no one in officialdom ever utters the names James Monroe or John Quincy Adams. Here again, the history of the Monroe Doctrine supplies a yardstick for evaluating present-day foreign policy and strategy.

History need not repeat itself precisely to render valuable service. In fact, the differences between then and now may enlighten more than do the likenesses. So crack open an old volume of U.S. diplomatic history—and learn a lot about the present day.

James Holmes is J. C. Wylie Chair of Maritime Strategy at the U.S. Naval War College and Contributing Editor at 19FortyFive. The views voiced here are his alone.