Haste. That’s a recurring theme in Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Mike Gilday’s 2021 “Navigation Plan,” released this week. The Navigation Plan is a directive subsidiary to the “Triservice Maritime Strategy” published by the U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard last month. It explains how the navy should and must do its part to execute the Maritime Strategy.

On Monday Admiral Gilday addressed the Surface Navy Association annual symposium, sounding that same theme. “I don’t mean to be dramatic,” he told reporters, “but I feel like if the Navy loses its head, if we go off course and we take our eyes off those things we need to focus on, I think we may not be able to recover in this century.” Because China’s naval and military buildup has progressed so swiftly, he declared, “I just sense that this is not a decade that we can afford to lose ground.”

Gilday’s sentiment is fitting. The hour is late. The state of the long-term strategic competition between the United States and Communist China demands urgency from top leadership.

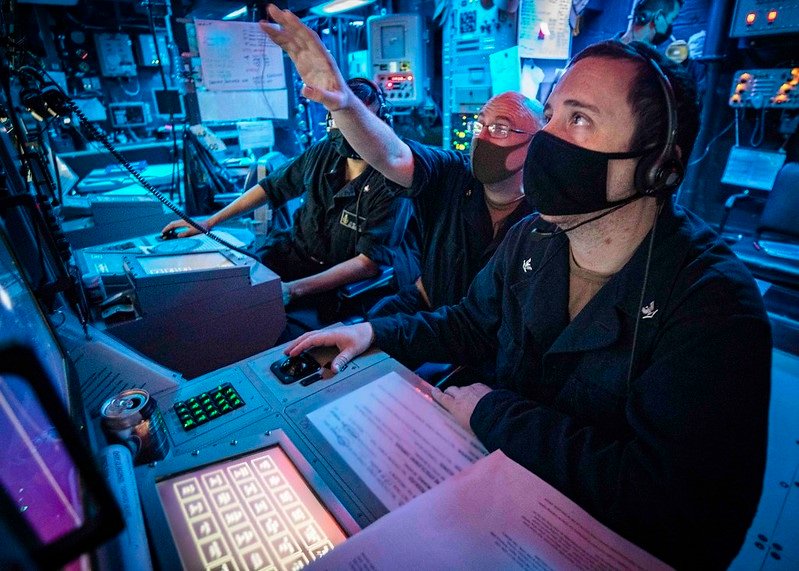

PHILIPPINE SEA (Dec. 15, 2020) Chief Sonar Technician (Surface) Mark Laurence, center, from Oklahoma City, Okla., directs Sonar Technician (Surface) 3rd Class Jordan Lang, right, from Palm Desert, Calif., to search on a line of bearing on active sonar in the sonar control station aboard the Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS John S. McCain (DDG 56) during an anti-submarine warfare training evolution. McCain is assigned to Destroyer Squadron (DESRON) 15, the Navy’s largest forward-deployed DESRON and the U.S. 7th Fleet’s principal surface force. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Markus Castaneda) 201215-N-WI365-1346

Some tenets of the Navigation Plan bear spotlighting. One, the stakes are high, and what the sea service does now will ripple far into the future. The navy must accelerate efforts to remake itself to compete against rival great powers, and it can no longer afford to fumble around with shipbuilding—as it has with such programs as the littoral combat ship, the Ford-class aircraft carrier, and the Zumwalt-class destroyer. It must get new construction right starting with the new frigate project now in the works. “There is no time to waste,” says the CNO, for “our actions in this decade will set the maritime balance for the rest of the century.”

Framing daily activities in world-historical terms is unusual for naval officialdom. And yet Gilday may be right after the past two decades of procurement miscues—miscues the navy must transcend to restore its competitive fitness.

Two, the document sets priorities clearly and succinctly. China is America’s chief competitor. The navy must “sensibly manage global force demands and focus our investments on improving our advantages over China before addressing other challenges.” Elevating one priority means demoting others. With the aircraft carrier Eisenhower starting a “double-pump” deployment—the flattop’s second major overseas cruise within a year—operating patterns cast doubt on whether the Pentagon will honor Gilday’s desire for self-restraint. Eisenhower is evidently bound for what the CNO defines as a secondary theater, the Persian Gulf region—not for the Western Pacific, the theater that supposedly takes precedence. Running the fleet ragged for purposes of lesser importance bodes ill.

Gilday also observes that in a sense the future and the present are enemies. “Delivering a Navy ready to control the seas and project power across all domains now and into the future requires us to balance current operational demands, the urgent need for modernization, and the imperative of future readiness.” Nonstop operations today, whether in theaters of primary or secondary importance, spend down resources needed to update the fleet to implement the Maritime Strategy. Slow down the operational tempo too much today for the sake of future capabilities, and the sea services—perversely—squander their ability to shape the future strategic environment.

All the more reason to confine operations to regions most in need of a U.S. naval presence.

Three, the Navigation Plan reaffirms that the U.S. Navy will revert to its traditional core functions, sea control and power projection, even as it peers into the future. Its past portends what is to come. In the wake of the Cold War naval leaders proclaimed, in effect, that the sea services would never again face a peer foe and could afford to deemphasize preparations for high-seas combat. The U.S. Navy and Marine Corps could assume that the sea would be a safe sanctuary from which friendly naval forces could shape events on distant shores. The reality has sunk in that naval forces once again have to fight to get to the fight. “For the first time in a generation,” declares the CNO, “the seas are contested.” As the Triservice Maritime Strategy notes, mariners must gird to deny a hostile navy control of the sea at the outbreak of war, balking its aims while preparing to seize maritime command for themselves. Only after they control important waters can they turn their attentions wholesale to projecting power.

This back-to-basics approach to naval warfare is making a comeback—and not a minute too soon. Welcome back to history.

Four, the Navigation Plan includes a line that feels like a throwaway but should be central to any maritime strategy: “After hostilities cease, we persist forward to preserve long-term U.S. interests through sustained forward engagement.” CNO Gilday is describing how U.S. maritime forces compete before the onset of armed conflict and help enforce the peace after the gunfire stops. Grand-strategy sage B. H. Liddell Hart counsels war leaders to avoid fighting if at all possible, but to wage war—if forced to it—with a constant eye on the postwar peace. The navy may forfeit wartime gains through neglect if the leadership does not assay some foresight into the nature of the postwar order and plan ahead to help consolidate it.

Even a smashing victory at sea need not portend everlasting peace. Strategic competition will resume afterward, sooner or later. America will have denied an aggressor interests of permanent and surpassing importance to its leadership and society. Think about it. China, the foremost competitor named in the Navigation Plan and Triservice Maritime Strategy, will not forever yield its claims to, say, Taiwan or the Senkaku Islands. Beijing will try again at a later date. The sea services, then, must not rest on their laurels after prevailing in war. They must help guarantee the peace in the immediate aftermath of fighting, and they must resume preparing for war. To ready themselves for the next competition they must maintain a battleworthy culture, experimenting constantly with new weapons, tactics, and operational methods. Seafarers must strive to preserve and expand their combat advantages in peacetime in order to deter the vanquished from fresh aggression—or defeat them again should a new round of fighting come.

In short, naval leaders must prepare to enforce the peace as diligently as they prepare to fight. One hopes this future sea-service directives will expand on this mandate, making the case more fully and fervently for terminating armed conflict and upholding the peace. If so, Liddell Hart will smile—and American naval performance will improve.

Five, Gilday reaffirms that this is an age of joint sea power in which all U.S. armed forces will bring armed might to bear in near-shore combat. Under a family of concepts—Distributed Maritime Operations, Littoral Operations in a Contested Environment, Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations—“our forces will mass sea- and shore-based fires from distributed platforms” such as ships, planes, and ground units. Coordinated effort will harness not just U.S. Navy warships and aircraft but Marine amphibious forces, Air Force bombers and fighters, and potentially even missile-armed Army units. All of the armed services boast armaments and capabilities able to reach out to sea. All will be sea services in littoral combat.

That being the case, instilling saltwater-mindedness across the Pentagon is an urgent matter. Only thus can the services debate, draw up, and execute operations as a cohesive whole.

Six, the CNO restates a talking point about alliances that has become common currency in recent months. Seldom if ever does the United States wage war alone, and naval leaders have resolved to make that even more true. “We must continue operating interchangeably with key allies,” he says, “to expand the reach and lethality of our collective forces across the globe.” That keyword interchangeability goes beyond mere interoperability, the usual shorthand for forces able to work together across technical and human boundaries. It connotes genuinely multinational forces. Probably the best example of interchangeability to date: the Royal Navy carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth is slated to put to sea this spring with a U.S. Marine Corps F-35 fighter squadron comprising the majority of its fixed-wing air contingent. The more frequently and intimately allied services work together, the better they will fight together—and the louder the message of allied solidarity they will broadcast.

Bring on the democratic armada!

And lastly, CNO Gilday calls for refurbishing and upgrading humdrum hulls, infrastructure, and capabilities without which no globe-spanning naval force can prosper. It is impossible to overstate this imperative. To operate across transcontinental distances U.S. task forces need regular and lavish supplies of fuel, ammunition, and stores of all types. While sea-service leaders hope to break down the fleet into more, smaller, cheaper combatant and amphibious ships, augmenting its ability to “stand in” and defy hostile missile barrages, the imperative for logistical support will not abate. Just the opposite, more likely. In Gilday’s words, the combat-logistics force—the flotilla of oilers, ammunition ships, and stores ships that ferries matériel to deployed forces and furnishes support of all sorts—needs more vessels to “repair, rearm, resupply, refuel, revive, and rebuild” forces operating in remote theaters.

Without sufficient logistics and transport capacity, the sea services may as well pack it in. Their Western Pacific endeavors will be fragile and transient rather than resilient and stubborn in the face of enemy action. Service chieftains neglect the mundane at their peril.

The Navigation Plan is an entreaty to the U.S. Navy. It also hands lawmakers, administration officials, and ordinary Americans a yardstick for judging the navy’s progress toward a force able to compete with and defeat today’s antagonists. One hopes it finds a wide and attentive readership in Washington DC—and from sea to shining sea.

James Holmes is J. C. Wylie Chair of Maritime Strategy at the U.S. Naval War College and a Contributing Editor at 19FortyFive. The views voiced here are his alone.