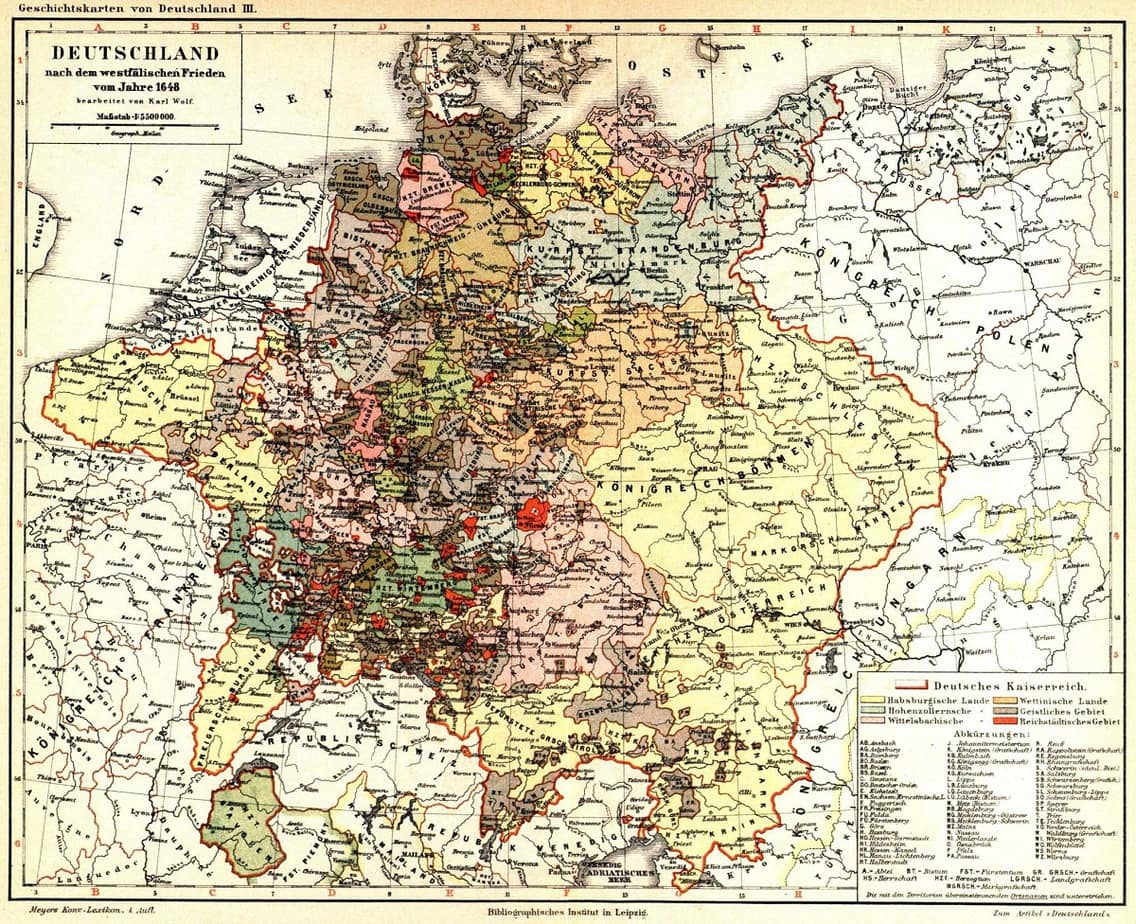

The year 2020 will be remembered by those who lived through it as one of the most challenging in recent memory. Amidst a global pandemic that induced generationally unprecedented levels of uncertainty and changes into society, the global community in 2020 witnessed a near-continuous trend of health, economic, and environmental setbacks throughout the year. Yet out of the ashes of such hardship, the Westphalian world order – that is, the concept of nation-state sovereignty based on the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia that under-girds the modern international community – has emerged as an unlikely winner amongst the chaos of 2020.

Much maligned in contemporary scholarship as a receding concept under pressure from the rise of non-state actors and complex interdependence, the power of nation-state sovereignty asserted (or reasserted) itself around the globe in 2020 demonstrating that the nation-state is not just alive and well amongst the fragmenting forces of transnationalism, but rather is poised to remain the preeminent unit in world affairs well into the future. Recognizing this “Westphalian Resurgence” must continue to shape the security strategy for the United States to ensure the correct prioritization of national security threats and leverage opportunities to pursue American interests and promulgate American values. On a broader level, heeding these global “Westphalian” impulses may be shaped to help establish conditions favorable to liberal-democratic values going forward.

In 2020, the “Westphalian Resurgence” manifested itself around the globe and in every major international power-center. In North America, the United States’ policy of “America First” dramatically re-asserted American sovereignty through its border security initiatives, efforts to secure more favorable international trade agreements, unilateral military operations, and pressure exerted on international allies to assume more of the security burdens around the world. In Europe, Britain culminated its efforts to leave the European Union (EU) providing a ringing statement of its sovereignty while decisively severing European influence or control over its institutions. In Asia, China continued to aggressively assert its sovereignty by cracking down on pro-democracy movements in Hong Kong and by initiating efforts to de-tangle its economy from the West. Finally, and perhaps most shockingly, in a series of agreements, several Arab countries in the Middle East agreed to recognize Israel’s sovereign right to exist (a Westphalian principle) in exchange for settlement concessions on the West Bank. In an area long motivated by a religious vision of world order and sovereignty that Henry Kissinger describes as a “total inversion” of Westphalian principles, the Abraham Accords in the Middle East and North Africa signaled a major victory for Westphalian world-order principles in the region historically most resistant to them.

It is important to note that the Westphalian “victories” described above carry with them separate moral judgments and implications that lie well beyond the scope or intent of this article. The moral rightness or wrongness of, say, the “America First” policy or China’s national security law for Hong Kong is certainly debatable. Even so, laying aside a moral judgment, what seems clear enough is that these developments firmly assert the Westphalian world order against the grain of contemporary literature and popular predictions.

Despite these 2020 global trends reinforcing the Westphalian world order, many continue to predict the downfall of the nation-state as the fundamental and most significant unit in the international community. Such critics point to a growing number of failed states as evidence of the nation-state’s decline. Indeed, in his prediction of Westphalian demise, a prominent scholar and author Sean Mcfate notes that only the “top 25 states” remain strong in today’s international community. However, meant as an indictment of the Westphalian world order, Mcfate’s words actually endorse it. If the top 25 most powerful states remain powerful, then McFate is admitting that the Westphalian structure to world order remains unthreatened by a rising number of failed states -even if weakness and turbulence characterize less powerful states. By analogy, no economist would predict the end of the banking system if the top 25 largest banks remained viable and strong. The same logic holds true in the international community with respect to the Westphalian world order.

Additionally, scholars have noted the appearance of non-state and transnational actors as threats to nation-state sovereignty. But non-state actors do not existentially threaten powerful nation-states. Moreover, the most powerful non-state actors seem to seek nation-state status once on the international scene. In a telling nod to the preeminence of the nation-state, the Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Shams (ISIS) promptly declared itself a “state” once it seized territory and began performing the functions of a Westphalian state. Such dynamics suggest that trends even among non-state actors ultimately affirm (not weaken) Westphalian principles.

Finally, many scholars point to the emerging economic interdependence between states as a weakening force on traditional Westphalian concepts of nation-state sovereignty. Such “complex interdependence,” they argue, is working to produce a “borderless world” with reduced functions for nation-states. But even as economic interdependence increases around the globe, global political interdependence has not correspondingly increased. Indeed, in many parts of the world, the only area that has matched or exceeded the economic interdependence ushered in by “globalization” is the simultaneous growth of nation-state governments to control or direct national economies. Can anyone, for instance, make a compelling case that the power of the U.S. and Chinese (the nations with the two largest economies) national governments are decreasing in response to economic growth? This diverging dynamic between economic and political interdependence better explains the increase of failed states noted above: increased economic competition (i.e. economic interdependence) amongst increasingly politically independent (i.e. increasingly sovereign) states produces greater inequality in nation-state capabilities. This, in turn, prescribes more pronounced and differentiated national winners and losers in the international community. Indeed, as Thomas Friedman notes, in a world with frequent economic interaction between nation-states with increasingly powerful concepts of sovereignty, nation-states that cannot compete get “eaten by the herd.” Thus, it is the strengthening (not weakening) force of Westphalian sovereignty principles driving the emergence of failed states.

Recognizing the 2020 “Westphalian Resurgence” is important for U.S. national security for several reasons. First, the trend confirms and affirms the wisdom and direction of the 2018 National Defense Strategy strategic shift from a focus on non-state terrorism to Great Power Competition- or, more accurately, Great Westphalian Power Competition (since Great Power competitors represent nation-states). Second, the resurgence suggests that policies that do not reinforce nation-state sovereignty as a top priority (without compelling reasons) risk being out of sync with global power dynamics. Thus, even as it’s perhaps wise to re-examine elements of the “America First” policy from the previous American administration, policies that carelessly undo sovereignty initiatives do so at precisely the time that other powerful nation-states are consolidating power under a reinvigorated concept of Westphalian sovereignty. Misreading the current trend will cause misidentification of security priorities. Like a homeowner changing the locks on his doors to prevent intruders while his house burns down around him, errant approaches to sovereignty in the contemporary environment confuse the important with the essential putting everything at risk. Finally, recognizing and affirming the Westphalian trends of 2020 gives nations the freedom (in fact the imperative) to pursue national interests (a distinctly Westphalian concept) above the illusions (attractive though they may be) offered by pursuing the Utopian “borderless world” of complex interdependence.

More broadly than its impact on U.S. policy, the “Westphalian Resurgence” in 2020 perhaps represents the initial tremors of globally felt instincts to re-establish the political context for international relations. The recent specter of Westphalian sovereignty’s collapse under the weight of a globalist “borderless world” theory of complex interdependence or the prediction of a world order dominated by non-state actors has perhaps caused societies and governments around the world to reflexively reassert (and re-value) their right to form unique and cohesive governments and societies. Even if not all nation-states that reasserted their Westphalian sovereignty in 2020 had liberal-democratic ideas in mind – in fact, some (i.e. China) explicitly repressed these values in the name of sovereignty- the resurgence may potentially help create conditions more favorable for improvements going forward.

As the global community collectively shakes the dust off its feet from a difficult 2020, it is worth remembering in the young new year that embracing the “Westphalian Resurgence” of 2020 is not just about revitalized nation-state sovereignty but also an affirmation of Westphalian principles. Such principles do not entail a rejection of international cooperation in favor of national isolationism. Rather, the Westphalian concept from 1648 is (critically) first and foremost a celebration and acknowledgment of the right of all nations to equal political, cultural, religious, and economic status as global community members (a sentiment that tracks closely with American values). With this as a guide, America should continue to embrace and champion a reinvigorated Westphalian world order as the surest way to secure and protect its interests while also leveraging the trend to articulate the best of American values to a global audience in 2021 and beyond.

Scott J. Harr is an Army Special Forces Officer and PhD Candidate at the Helms School of Government, Liberty University. He holds an undergraduate degree in Arabic Language Studies from West Point and a Masters degree in Middle Eastern Affairs from Liberty University. With over four years of cumulative deployment time around the world, his work has been featured in The Diplomat, RealClearDefense, The Strategy Bridge, Modern War Institute, Military Review-Journal, and Joint Force Quarterly.