The question put to me for today is: what are some aspects of the Western way of maritime war that opponents can exploit? I chose two, and elected to use sports—and in particular the concept of the home-team advantage—as my organizing device. The first aspect is this: Western sea services are almost always the visiting team. The United States has long pursued a “rimlands” strategy around the Eurasian periphery, which by definition means we have to travel intercontinental distances, probably through contested waters and skies, just to get to the field of battle. We have to fight to get to the fight, as a U.S. Marine commandant put it not long ago.

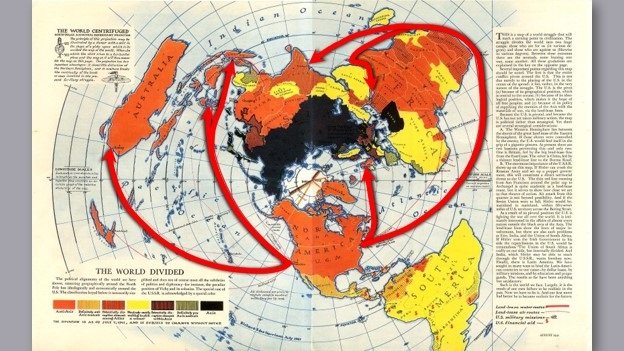

Just look at this World War II map demonstrating how Lend-Lease supplies got to overseas allies in mid-1941. The map hints at how an opponent might obstruct our access—you’ll notice the Axis had closed the Mediterranean to Allied shipping. The problem of geography is at least as vexing in the Pacific today as it was back then. And when we do get to the battlefield we confront a difficult strategic question. Namely, what happens when a fraction of your team goes up against the whole of a hostile team on that team’s home field or court?

Image courtesy of James Holmes.

Adversaries now predicate their strategies on trying to make that quandary insoluble for our leaders. What we call “anti-access” refers to using sea- and shore-based weapons and sensors to keep an opponent’s reinforcements from ever reaching the stadium, “area denial” to using those systems to attack players already on the field, such as the Japan-based U.S. Seventh Fleet and affiliated joint forces. Chinese anti-access strategy envisions pummeling U.S. forces forward-deployed along the East Asian rimland while preventing the larger U.S. Pacific Fleet from reaching the battleground from its home ports in Hawaii or on the west coast in time to affect a war’s outcome. In other words, the Chinese Communist Party wants to set the terms of access to its maritime environs. This is a nettlesome problem for expeditionary forces.

The second aspect is this: Western maritime services fight in “systems” that depend heavily on the electromagnetic spectrum to pass information and instructions to the constituent parts of the system and back. The components—the nodes in the system—are ships, planes, armaments, sensors, and so forth. A system could be a large formation such as a fleet, amphibious brigade, or expeditionary air force. It could be something smaller, like a surface action group. Taking the concept to its extreme, an individual warship is itself a “system of systems,” relying on various subsystems to propel the hull through the water, generate electricity, detect, track, and target hostile forces, and on and on. The same goes for other complex platforms.

This interdependence among subsystems creates opportunity for our competitors. Attacking a military system may, but need not, involve “kinetic” measures such as missile attacks. If an adversary can reach into that ship and disrupt its internal workings, it is carrying out a type of “systems-destruction” attack. It could make mayhem by launching a cyberattack; it could even use social media to distract and confuse the crew. So our dependence on the EM spectrum creates opportunity for a local defender to disrupt our operations. To continue with our sporting analogy, this is roughly akin to a hostile home crowd shouting at the top of their lungs to interfere with coaching decisions or communications among the visitors. And indeed, China’s People’s Liberation Army thinks in terms of defeating systems rather than military forces as traditionally understood. We need to comprehend this strategy to vanquish the home team on its own turf.

So Western sea services face stubborn problems of geography and technology, along with asymmetries in how we make war. How do we work around these problems? What I have to say about potential remedies is simple; but as Clausewitz reminds us, the simplest thing is difficult to pull off in strategic competition and warfare. Let me offer six general recommendations:

First, we must politically diversify our system—our combined armed forces—by making our alliances indivisible. We have made progress on this front, to the point where U.S. Navy commanders now talk about “interchangeability” among allied forces rather than mere “interoperability,” which refers to the ability to work together despite dissimilar hardware, tactics, or procedures.

Rather than assemble a task force out of units from multiple sea services, which has been common practice since the inception of NATO or the U.S.-Japan security alliance, interchangeability could result in mixed crews and true integration. In fact, it is happening here in the Atlantic before our eyes. The push for interchangeability is especially noteworthy in the realm of carrier aviation. The Royal Navy’s first supercarrier, HMS Queen Elizabeth, is preparing to make its first deployment with a U.S. Marine F-35 squadron making up the bulk of the vessel’s fixed-wing aircraft contingent. French fighter pilots have flown from U.S. flight decks to stay proficient when their home carrier was undergoing a refit. Just last week the Italian carrier Cavour put into Norfolk, Virginia to certify its crew to operate F-35s. These are feel-good news stories. The more allied fleets come to resemble a unified democratic armada, the better. Mingling people and hardware puts potential foes on notice that no antagonist can splinter our military fellowships in wartime. It announces that we have skin in the game of our common cause.

Second, we need to make geography our ally. The complex thing about maritime East Asia is that not just one home team but two—China and Japan—have taken the field. In fact, they have carried on a running series since about the seventh century. Japan has been on top since 1895, China wants to avenge past defeats, and the U.S.-Japan alliance wants to keep the streak going. Using Japanese geography in concert with sea power could let us give China a very bad day by bottling up naval and mercantile shipping within the first island chain, or preventing whatever happens to be outside the island chain from returning home. Sorting out the politics of island-chain warfare is of prime importance in the strategic competition, as is assuring our navies and air and ground forces can fight together in the near-shore domain. If successful we will make the U.S.-Japan alliance the dominant home team along the island chain.

Third, we must diversify the system militarily by adding more nodes. This is partly a function of alliance relations, as I noted. More partners are better; they add assets to the team. I am sensing a recurring theme here: alliances! It’s partly about tapping the maritime potential of armies and ground-based air forces, which are increasingly able to shape events at sea and can coordinate with fleets. It’s partly about new construction, adding more nodes to the system in the form of ships, aircraft, and sensors. And it’s partly a matter of dispersing firepower more widely—presumably aboard a bigger fleet of smaller ships and planes, an increasing share of them unmanned and perhaps autonomous. By adding raw numbers of hulls and airframes while spreading out weaponry among them, we concentrate a smaller percentage of our aggregate combat power in each node. That means the system as a whole can absorb losses and carry on.

Fourth, we need to harden the system, making it hard for an antagonist to cut the sinews binding it together. What Chinese strategists call “systems-destruction warfare” aims at weakening or breaking the links that hold a system together and then attacking its scattered nodes. To defeat this mode of sea combat Western forces need to assure mutual support and connectivity among the nodes. Efforts to fortify a system against attack will unfold mainly in such shadowy realms as cyberwarfare, electronic warfare, and management of the force’s electromagnetic signature. A mix of offensive and defensive measures will make it rougher on an opponent to fragment our systems.

Fifth, we should identify substitute hardware and methods in advance so that operators have a fallback in case a successful kinetic or non-kinetic assault fractures the system. This might, but need not, involve developing some sort of high-technology solution. It might involve reverting to older but time-proven methods. We might even see signal flags or flashing-light signals make a comeback in fleets riding the waves. To name one such reversion to past practice, the U.S. Navy has made a long-overdue course correction in recent years by reinstating celestial-navigation training at navy schoolhouses. By relearning how to navigate by the stars, we partly weaned our ships away from GPS, any savvy opponent’s prime target in wartime. Furthermore, newly developed weapons are designed to function in a degraded tactical setting. The logic behind such measures is straightforward. If we can’t find our way from point A to point B or detect, track, target, and engage enemy forces, we can accomplish little—even if the foe never shoots down one of our planes or sinks a ship. So developments such as these are all to the good.

And sixth, we need to ensure our joint doctrine is adequate and that the people overseeing the system’s components are well versed in it, so they know what to do should they find themselves cut off from communication with or coordination from top commanders. Much as the visiting team has to cope with hostile crowd noise that interferes with play-calling and execution, we need to expect the home team to use its advantages to interfere with our command-and-control—and prepare our players to function effectively despite degraded tactical and operational conditions. Practicing the way we expect to play will make this second nature for seafarers—and improve our prospects for an acceptable outcome to a fight. If we convince an opponent like China that we would win, we improve our chances of never having to play a game none of us wants to play. The opponent will forfeit—or, at any rate, postpone seeking its goals by force. Good things could happen in the meantime.

So prevailing is tough when you’re the visiting team. Fortunately, sea-service leaders realize we have a problem. If we put our heads and resources together as allies and friends, we stand a good chance of solving that problem.

James Holmes is J. C. Wylie Chair of Maritime Strategy at the Naval War College and Contributing Editor at 19FortyFive. This week two of his books, A Brief Guide to Maritime Strategy and Red Star over the Pacific, were named to the Chief of Naval Operations Professional Reading List. The views voiced here are his alone.