The Taliban takeover of Kabul has thrown Afghanistan’s future into a world of chaos and uncertainty, but there is no question that it has destabilized the geopolitical status quo in Southwest Asia, with consequences that will reverberate for decades.

Taliban rule in Afghanistan has significant implications for security in the Mediterranean region as well. Shortly after the fall of Kabul, Turkey, a NATO ally, made a series of public statements welcoming the Taliban’s return.

In a press conference in Jordan, Turkish Foreign Minister Melvut Cavusoglu told reporters that “We are keeping up dialogue with all sides, including the Taliban.” He added that Turkey views the messages the extremist group has sent out since taking control of Kabul very positively.

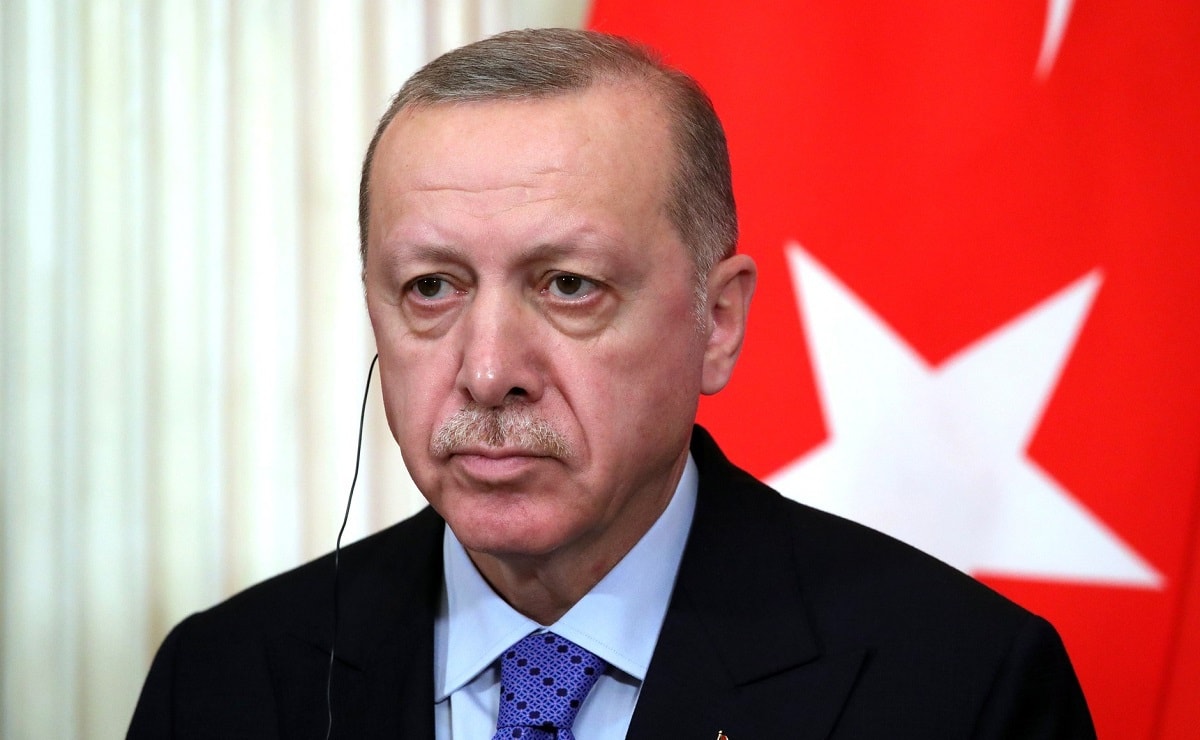

But it also seems that Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan is ready to offer more than just rhetorical support to the Taliban while simultaneously playing both sides. Anonymous sources inside the Turkish government told Reuters that while Turkey withdrew its NATO security forces guarding the Kabul airport, a move that was in line with other members of the alliance, Ankara was ready to provide troops to support the Taliban if it so requested.

When the United States was set to finalize its withdrawal from the country, Turkey originally planned to keep 600 troops there to guard and operate the airport amidst the chaos that was bound to ensue after the rest of NATO forces had left. However, the reality of the situation on the ground forced Ankara to withdraw when other allied troops did.

“At this stage, the process of Turkish soldiers taking up control of the airport has automatically been dropped,” said one of the sources speaking to Reuters. “However, in the event that the Taliban asks for technical support, Turkey can provide security and technical support at the airport.”

Erdogan, who has criticized the speed of the Taliban’s advance on Kabul, apparently viewed the airport mission as a peace offering to NATO allies, seeing an opportunity to mend relations.

Some mending of Turkey’s relationship with the rest of the alliance is indeed called for. It has been a complicated ally at the best of times. Among other incidents, Turkish naval ships harassed a French one during a routine inspection of a third vessel in the Mediterranean in June 2020. A likely motivation was France’s military support for Cyprus, whose sovereign waters Turkey has violated while exploring for oil and gas. The incident led to France’s withdrawal from NATO’s Operation Sea Guardian mission.

Going back even further, Turkey’s behavior has seemed to suggest that the Erdogan government is rejecting the alliance in favor of more authoritarian power brokers in its vicinity that align with the anti-democratic tendencies of Erdogan. In 2017, the Erdogan government purchased a set of S-400 missiles from Russia, resulting in Turkey’s ejection from the coalition of countries that operate the F-35 fighter. After the purchase, Erdogan’s relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin became increasingly close.

Following a recent call between Erdogan and Putin, Erdogan’s office issued a statement affirming a joint commitment of Russia and Turkey to recognize and establish ties with the Taliban on a “gradual” basis. “President Erdogan and Russian President Putin agreed to coordinate the relationship to be developed with the government to be established in Afghanistan in the upcoming period,” it read. The statement also asserted Turkey’s willingness to resume operations at the Kabul airport.

Erodgan’s attempt at a cooperative gesture aside, it is this cumulative history that makes Turkey’s support for the Taliban bode worse for its allies than if it had come out of nowhere. The danger to the rest of the alliance, perhaps especially in the Mediterranean, will be heightened in the imminent future. Tacit permission from Ankara could give extremists a quicker channel to target places were attacks were previously rare or nonexistent.

The strongest indicator of this is the fact that Erdogan’s government has turned a blind eye to extremist activities on its border and the surrounding area, viewing their presence as beneficial to Turkey’s interests, while simultaneously targeting NATO’s Kurdish allies in the fight against ISIS. With the Taliban once again in control of Afghanistan, those extremist groups will likely find sanctuary there just as they did twenty years ago. If that turns out to be the case, the Erdogan government may likewise view Taliban rule as bolstering favorable political conditions for Ankara.

But the return of the Taliban does not make Turkey safer. While Turkey welcomes the change now, Ankara is putting itself at risk in the future. During the U.S. and allied occupation of Afghanistan, terrorist attacks have taken place in both rural parts of the country as well as in the capital and Istanbul.

Nor does having the United States out of the picture set Turkey up to wield greater influence in the Mediterranean or the wider Middle East, though it may plausibly feel emboldened to escalate its aggression against allies such as Greece and Cyprus in an attempt to assert itself as a regional power player.

Just as it has been posited that China, Russia, and Iran will stand to seize on new opportunities to expand their influence abroad after the U.S. fully withdraws, the rewards of those ventures are uncertain and likely to come at a cost. The unpredictable and insular nature of the Taliban makes any benefit to countries like Turkey, as well as China, Russia, and Iran, impossible to guarantee.

Sarah White is Senior Research Analyst at the Lexington Institute.