As the aftershocks of the AUKUS announcement rumble around the world, the notoriously thin-skinned French continue to let their inflamed passions reign over all good sense. The reasons are twofold, and relatively obvious, but a worrying consensus seems to have emerged among the commentariat that Australia should have behaved better. That they should, for example, have consulted with their French ally more effectively, and perhaps included them in the new arrangements. That the snub, when delivered, needn’t have been so dismissive. That France, in effect, ought to have been better respected.

It is always tempting after an argument to imagine that if only bitter truths had been phrased more delicately, and tactful proprieties observed with greater diligence, that pills could have been made easier to swallow, and blows more carefully cushioned. Those that make these sorts of arguments always sound, retrospectively, decent and honorable, like the better persons they imagine themselves to be. But it is a conceit. It implies that the pill taker sees the pill as medicine, not poison, that the victim agreed to rules that determine what amounts to a fairly delivered punch. This was not so. The Australian government got itself out of a bad deal (in its view) and stiffing the French was the only effective way to do it. Pretending otherwise pays far too much attention to French histrionics, and fails properly to credit the Australian government with a diplomatic masterstroke that has radically reshaped the future of the Indo-Pacific. Scott Morrison may be routinely scorned as an advertising man by temperament, but he clearly read Machiavelli more closely than his critics, or at least more closely than they thought he had.

Simply put, the route out of the French submarine deal involved a significant risk of diplomatic and strategic isolation for Australia, and at a time when Canberra simply cannot afford to expose itself in this way. The French are understandably upset, but the real anger is at the fact that the contract has been junked, not the way it was done. This is realpolitik, and the Australian Prime Minister has shown himself to be a ruthless operator. Perhaps Australia’s first. He has surprised the French by acting, well, French. Whatever his critics argue, there was no way to sugar this pill, and for France to be abandoned by what they regard as a second-tier power was always going to bring out the worst of their habitual anglophobic scorn.

Comme Un Double Coup

For the French, the impact of losing the contract is twofold; economic and symbolic. Economically a contract of this size and sophistication is enormously important for a large, industrial power like France. It is valuable in its own right, supporting jobs and investment in a crucial sector, and would have helped France remain at the technological cutting edge by underwriting its own self-sufficiency in defense technology. It was comparable in some ways to the UK’s huge contracts to supply Saudi Arabia with Tornados and Typhoons. On this level alone it is therefore a large setback for France, which would entirely justify a level of anger on their part.

Far more important from the French perspective though is the symbolism of losing a carefully cultivated strategic partner that had appeared to support French claims of great power status. Though many have referenced French NATO (or OTAN if you prefer) membership, there has always been a sense in which France remains semi-detached from the more integrated US defense penumbra encompassed by the UK, Canada, Australia, Japan and others. Their relationship with the US, and other Anglo powers is at once close, and prickly. British officers will tell you that they cooperate well at an operational level, but at a political level the French never tire of distancing themselves when they deem it appropriate. This is merely a feature of their long-standing efforts to carve out some middle position, close to the Americans when necessary, but an outlier on matters ‘grand’, a presumed equal in the discourse of civilizations upon which a pluralistic order might eventually emerge. This habit of blowing hot and cold comes out best at moments like this when an Australian decision is blamed almost wholly on the US, who in French eyes are obviously in control of everything behind the scenes. They cannot admit that the Americans don’t really see France as a competitor, so much as a fair-weather friend. It pulls back the curtain on their Gaullist illusions.

The pique directed at the British, however, is spectacularly fierce and condescending, referring to them as a ‘fifth wheel’ and a ‘dishwasher’ not even worth the diplomatic snub of a recalled ambassador. Remarkably, Jean-Yves Le Drian, French Defence Minister, complained bitterly about being left out of the new arrangements, despite also referring to them as a kind of ‘willing vassalage’. All very droll, of course, and Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s descent into humorous ‘franglais’ was pitch perfect banter, contrasting French passionate volubility, with slightly amused (though pretending to be bemused) English sang froid. Bruno Tertrais, a prominent French commentator on strategic matters also clumsily referred to the whole affair as a ‘Trafalgar moment’, an outcome likely to be seen as satisfactory in Whitehall given how that turned out. But also noteworthy because the Royal Navy currently deploys two nuclear-powered hunter-killer submarines of the Trafalgar class, and will soon launch an Astute-class submarine named HMS Agincourt, battles in which the English defeat the French being a favored inspiration when naming Her Majesty’s vessels.

A Better Way?

The French were never going to react well to the long-anticipated cancellation of the submarine contract, but what happened was far worse than that. Indeed, the anger they have shown was likely planned to some extent and implied in their recent negotiations with Australia. Canceling a contract is freighted with strategic implications which the French would have highlighted, suggesting to the Australians that if they were to cancel the contract, they would be isolated. They might even have suggested that they would work strenuously to discourage the US from assisting in any way, especially now that President Biden was making such a priority of repairing alliances. And as for the British, insert stinging French diploslap here, ‘Hon Hon Hon!’

Given the known problems with the contract and the decision to upgrade to the considerable advantages of nuclear-powered subs Australia, therefore, faced a choice. They could either do the decent thing and cancel the French contract first, before talking to new partners, which would run the risk of severe diplomatic subterfuge from both France and China doing their utmost to ensure Australia did not take this step towards nuclear-powered subs and a reinforced strategic partnership with the US and the UK? Or alternatively, arrange it all secretly with their closest allies and announce it as a fait accompli? It’s obvious, even in retrospect, that Scott Morrison made exactly the right decision and should not under any circumstances apologize for it.

At a certain level of international politics, there are no nice guys, just hard decisions. The French strategy of positioning itself between the US and China, along with a string of middle powers, from India to Japan makes sense in a calmer world where competition is relayed through institutions. That world is drifting away from us now and Australia has had to change tack. Other powers, even France, will likely follow Australia’s lead and make their alliances more explicit in the coming months and years, but Scott Morrison has found exactly the right bullet to bite for now. For its part, France has already returned its ambassador to Washington and secured from the US a measure of indulgence for its notion of EU defense, though not, importantly, from the rest of the EU just yet. But this merely reveals that the point of this whole exercise was never to discomfit the French. The point was to upgrade Australian capabilities and lock in US/UK defense cooperation into the Indo-Pacific. French amour propre was just roadkill.

040825-N-5268S-002

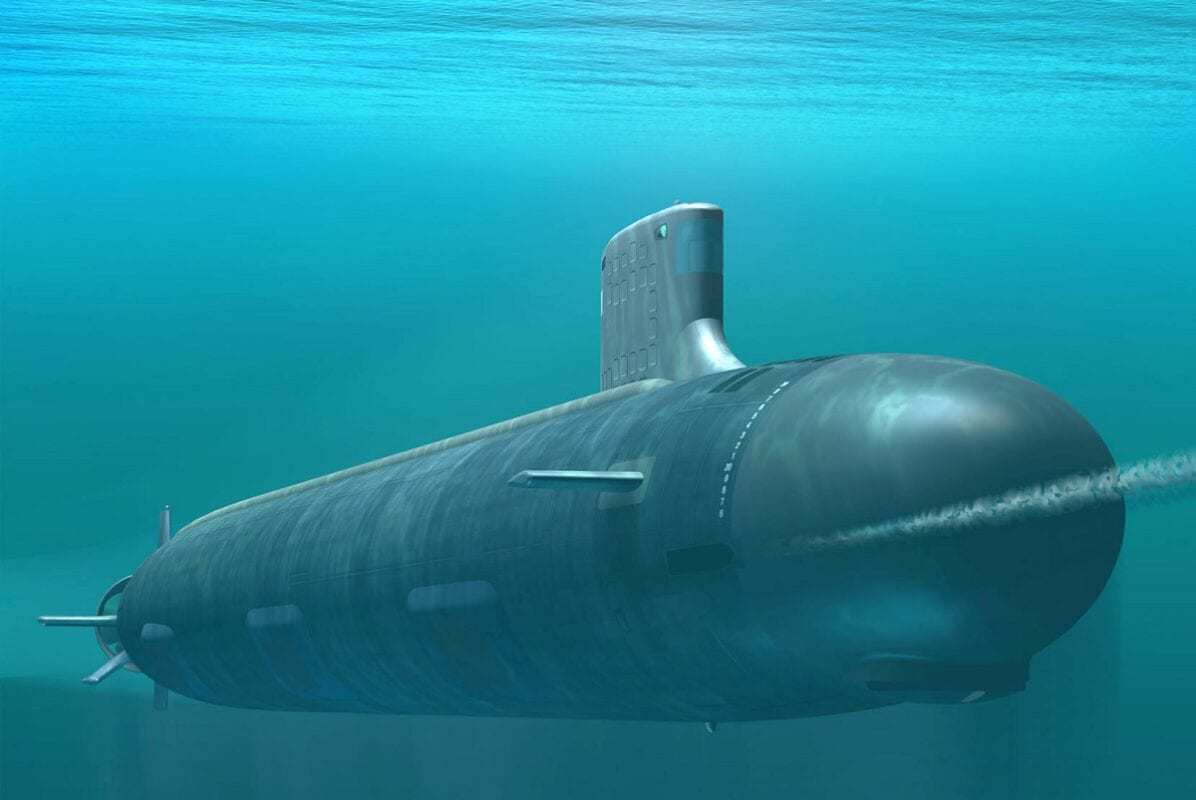

Portsmouth, Va. (Aug. 25, 2004) – The nationÕs newest and most advanced nuclear-powered attack submarine PCU Virginia (SSN 774) passes the skyline of Portsmouth, Va., on its the way to Norfolk Naval Shipyard upon completion of Bravo sea trials. Virginia is the NavyÕs only major combatant ready to join the fleet that was designed with the post-Cold War security environment in mind and embodies the war fighting and operational capabilities required to dominate the littorals while maintaining undersea dominance in the open ocean. U.S. Navy photo by Journalist 2nd Class Christina M. Shaw (RELEASED)

030521-D-9078S-001

(May 21, 2003) — This conceptual drawing shows the new Virginia-class attack submarine now under construction at General Dynamics Electric Boat in Groton, Conn., and Northrop Grumman Newport News Shipbuilding in Newport News, Va. The first ship of this class, USS Virginia (SSN 774) is scheduled to be delivered to the U.S. Navy in 2004. U.S. D.O.D. graphic by Ron Stern. (RELEASED)

We can all pretend that the Morrison government ought to have treated the French with more respect, but the fact that he did not say a thing reveals merely that the French were not, in the final analysis, trusted to respect the priority of Australia’s national interests over their own commercial and strategic concerns. It further indicates that, in Australia’s estimation, the French would have been unlikely to believe any proferred reassurance that it wasn’t personal. Instead, the fact that the French has taken it so personally, and with such dramatic and public frustration is exactly the reason why the Australians were right to behave as they did. Of course, Scott Morrison should take no pleasure in embarrassing French strategic pretensions, but nor should Australia be expected to indulge them at their own expense either. The world is rapidly growing more dangerous. Australia has reacted with AUKUS, not AUFRUS. There is a reason for that.