The U.S. Air Force remains the sole operator of the stealth Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor, an aircraft widely regarded as the most dominant fighter in the world. It is especially respected for its dogfighting ability and air-to-air maneuverability attributes. Primarily designed as an air superiority fighter, it also offers ground attack, electronic warfare, and signals intelligence capabilities.

Ask many aviation experts, and they’ll be quick to tell you that the F-22 is unrivaled in the world. Of course, not everyone agrees with that assessment, notably those in China’s People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF), and instead touted the capabilities of its Chengdu J-20 “Mighty Dragon.”

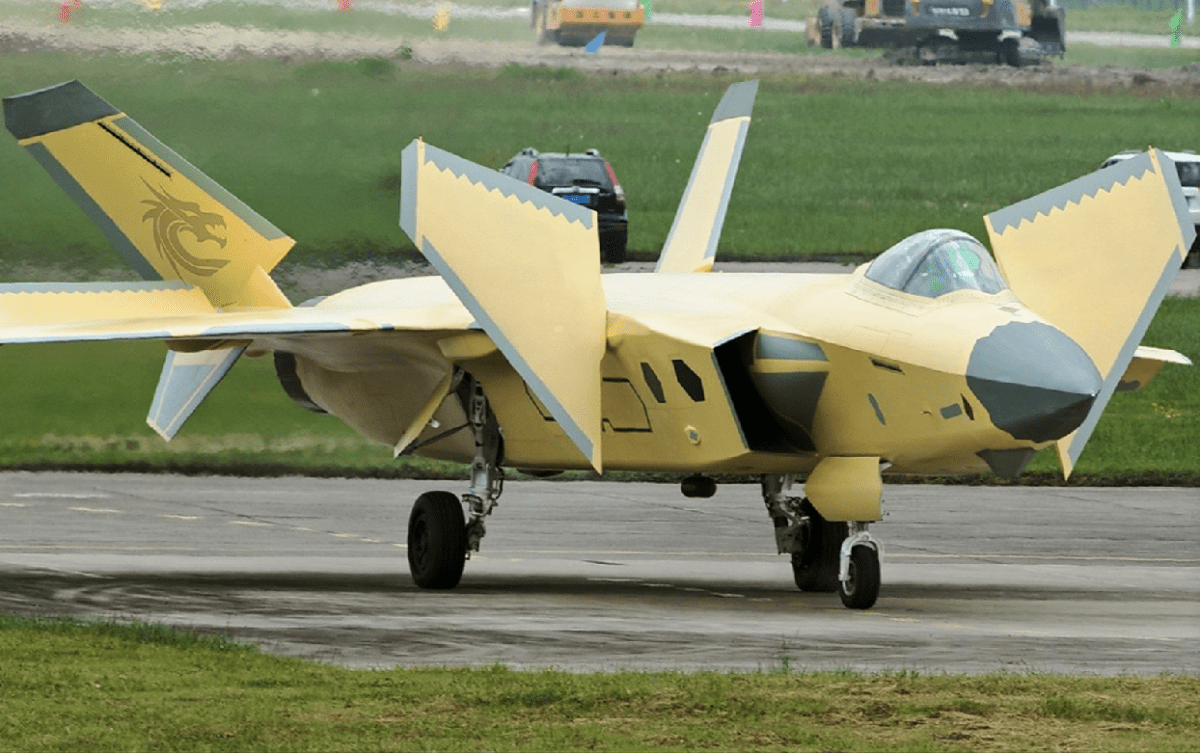

It is true that the J-20, which came about from Beijing’s J-XX program in the 1990s and only made its maiden flight on January 11, 2011, is a newer platform. In fact, it only began test flights a year before production ended on the F-22 Raptor. As the world’s third operational fifth-generation stealth fighter, after the F-22 and the Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II, the J-20 had the advantage of building on what worked.

It also likely didn’t hurt that China likely stole U.S. technology to develop the J-20. Yet, there is a problem with simply copying (stealing), and as has been seen in almost everything that comes out of China the result is an inferior product. Reverse engineering doesn’t result in an improvement. This is true whether it is golf clubs, smartphones, athlete shoes, or aircraft carriers.

The J-20 thus lacks the capabilities of the F-22, and despite the boasting from Beijing, it was also simply meant to be a starting point to serve as a stepping stone for more advanced aircraft to come. That’s the Chinese way of innovating. Copy first, improve after.

Comparing the Designs

The J-20 and F-22 do share many similarities. The J-20 fuselage appears to resemble that of an F-22 with two engine exhausts and a blended, curved, or rounded main body exterior. At 69 feet, seven inches, the Chinese J-20 is slightly larger than an F-22, which is 62 feet, one inch in length. However, the wing configurations of a J-20 and F-22 are decidedly different, with the J-20 having a slightly smaller wingspan and total wing area.

Both combat aircraft utilize internal weapons bays, allowing them to maintain higher performance than fourth-generation combat fighters. The J-20 is also a lighter aircraft but has a larger internal fuel capacity.

While the exact capabilities of the Chengdu J-20 haven’t been largely disclosed, the Chinese have struggled to provide an adequate powerplant for the fighter. It was initially powered by the Russian-made Al-31F engines, as well as the indigenously-produced WS-10B. Each of those engines was designed for less advanced aircraft. Moreover, efforts to produce a new engine, the WS-15, also came up short when it failed its final evaluation in 2019.

As a result, engineers have been fitting the aircraft with the WS-10C, an upgraded version of the original WS-10. With the WS-15 engine, the J-20 is believed to have a range of 1,200 miles (2,000 km) and a servicing ceiling of 66,000 feet (20,000 meters), and a maximum speed of Mach 2.55 or higher.

A 1st Fighter Wing’s F-22 Raptor from Joint Base Langley-Eustis, Va., pulls into position to accept fuel from a KC-135 Stratotanker with the 756th Air Refueling Squadron, Joint Base Andrews Naval Air Facility, Md., off the east coast on May 10, 2012. The first Raptor assigned to the Wing arrived Jan. 7, 2005. This aircraft was allocated as a trainer, and was docked in a hanger for maintenance personnel to familiarize themselves with its complex systems. The second Raptor, designated for flying operations, arrived Jan. 18, 2005. On Dec. 15, 2005, Air Combat Command commander, along with the 1 FW commander, announced the 27th Fighter Squadron as fully operational capable to fly, fight and win with the F-22.

U.S. Air Force Maj. Paul Lopez, F-22 Demo Team commander, performers aerial maneuvers July 14, 2019, at the “Mission Over Malmstrom” open house event on Malmstrom Air Force Base, Mont. The team flies at airshows around the globe, performing maneuvers that demonstrate the capabilities of the fifth-generation fighter aircraft. The two-day event, featured performances by aerial demonstration teams, flyovers, and static displays. (U.S. Air Force photo by Airman 1st Class Jacob M. Thompson)

Powered by two Pratt & Whitney turbofan engines, the F-22 Raptor is capable of reaching speeds of Mach 2 (1,534 mph/2,469 kph). It has a ceiling of 50,000 feet (15 kilometers) and a range of 1,841 miles (2,962 km) without refueling. Unlike the J-20, however, the F-22 is able to reach supercruise speed and more importantly sustain it without the need of afterburners.

It is possible that the J-20 will be improved – including finally being equipped with an engine worthy of the airframe – yet for now, the Mighty Dragon seems to be a mere facsimile of the Raptor. Both are likely capable aircraft, but the Raptor’s claws and better maneuverability could give it an advantage in a match-up with the Mighty Dragon.

J-20 Stealth Fighter

Image: Chinese Internet.

Image: Chinese Internet.

Now a Senior Editor for 1945, Peter Suciu is a Michigan-based writer who has contributed to more than four dozen magazines, newspapers and websites. He regularly writes about military hardware, and is the author of several books on military headgear including A Gallery of Military Headdress, which is available on Amazon.com. Peter is also a Contributing Writer for Forbes.