Iraqi politics are messy. The country is a democracy, and no single individual is able to dominate the country. Unlike their counterparts in Syria, Egypt, or Turkey, Iraqi governments enter elections without knowing their future.

That said, the process is flawed. Various parties go to the polls, but the real powerbrokers remain unelected, operating behind the scenes. An initial U.S. and United Nations rush to elections in Iraq compounded the problem by imposing an election system that appeased and empowered these unelected figures.

Even as the White House and State Department speak about democracy in Iraq, their approach to Iraqi politics is little different than that of Tehran. Rather than improve Iraqi democracy and combat the country’s plague of corruption, American officials choose instead to work through Iraqi powerbrokers and warlords.

Consider, for example, the numbers of American officials who meet Masoud Barzani, the former president of the Kurdistan Region, who today holds no formal, elected position. Across Democratic and Republican administrations in Washington, officials treat Barzani as if he were an indispensable man.

U.S. officials regularly denounce Iran-backed militias controlled by powerbrokers like Hadi Amiri or Qais Khazali who seek to impose through force of arms what they cannot achieve at the ballot box. Few American officials acknowledge, however, that the Kurdish peshmerga today do the same thing. While 40 years ago, the peshmerga displayed heroism and stamina in their fight against Saddam Hussein’s regime, today they are little more than U.S.-funded militias that, like their Iranian-backed counterparts, exist less to provide security, and more to advance the personal political and financial interests of political leaders. In Baghdad, the targets of the Badr Corps’ or Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq’s violence are likely to be journalists, business competitors, or rival politicians. In Erbil and Sulaimani, the same holds true with regard to the various Kurdish families’ peshmerga.

Seldom has the American overreliance on individuals worked. The United States openly backed former Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhimi, for example, believing they could use him to combat militias and tilt Iraq away from Iranian influence. Not only was Kadhimi ineffective, but the stink of his corruption now also sticks to America and leaves Iraq worse off than it was before he started. The State Department should require American diplomats who ran interference for Kadhimi to clip Simona Foltyn’s “Heist of the Century” expose to their cubicles for the rest of their careers.

When it comes to Iraqi Kurdistan, the reliance on specific Kurdish officials is likewise self-defeating, not only for the development of the region itself, but for all of Iraq. In 2018, for example, White House official Brett McGurk pressured Kurdish politician, reformer and technocrat Barham Salih to stand down in his run for the presidency in favor of Barzani’s choice, Fuad Hussein, a man of questionable qualifications to serve in Erbil, let alone in Baghdad. McGurk appeared to be driven by fear that if Barzani did not get his way, his resulting tantrum could throw a wrench into Iraq’s functioning and its recovery from the Islamic State. It is amazing that almost 20 years after Saddam’s ouster, the United States still falls for Barzani’s blackmail. Its genuflection never paid dividends.

Alas, history repeats. While the United States opposed Barham’s presidency in 2018, it eventually came to count on him. While the Iraqi Constitution limits the president’s power, Barham’s skill helped Iraq navigate difficult and dangerous situations arising from a popular protest movement, the hemorrhaging of Iraqi government power, and Kadhimi’s ineffectiveness. Barham also raised Iraq’s diplomatic profile, capped off by Pope Francis’ 2021 visit to Iraq.

Masoud and Masrour Barzani, however, took an “anyone but Barham” approach based not on what was good for Iraq, but instead rooted in their own tribal concerns. They initially nominated relative Reber Ahmed Barzani, but no amount of political bribery could make the family functionary acceptable even to Barzani’s political allies in Iraq.

Rather than reject Barzani or coerce him with sanctions or an end to the U.S. subsidies he treats as an entitlement, White House officials sought to compromise with him, assuaging his ego by treating his position as legitimate. The result was a compromise that ejected Barham and replaced him with Latif Rashid, late President Jalal Talabani’s brother-in-law. While the 78-year-old Latif comes from the same political party as Barham, he approaches the position with considerably less energy.

Fair enough. Politics is a blood sport. Barham has often been down, but has never been out. Nor should any system depend on a single person. The question McGurk, and other American officials should ask, however, is what benefit there was to appeasing Barzani. Did it undercut Iranian influence in Iraq?

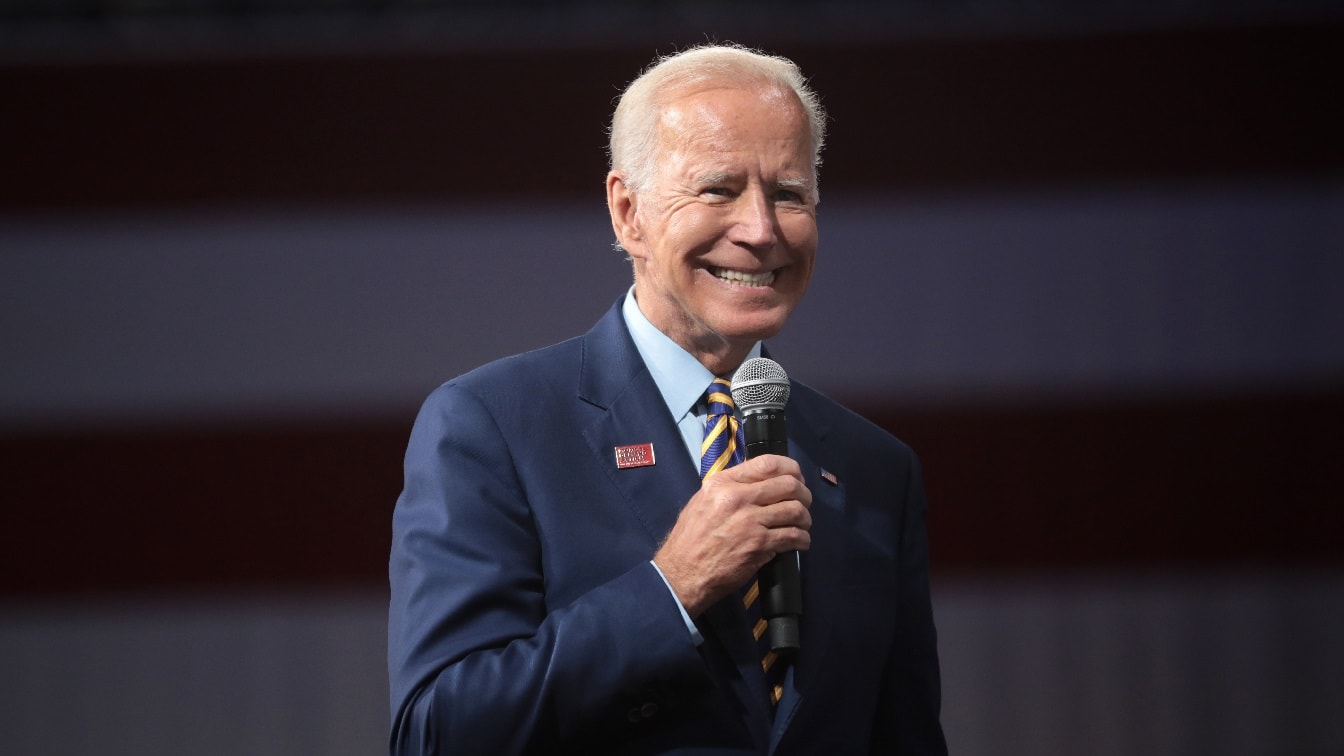

No. In hindsight, Barham was an important check on the ability of pro-Iranian power broker Nouri al-Maliki to undermine liberal interests. Did compromising with Barzani further reconciliation in Iraq? No. By appeasing Barzani, the Biden administration signaled it would ignore and forgive his 2014 double game with the Islamic State and his 2017 efforts to secede from the country. Did kowtowing to Barzani bring intra-Kurdish peace? No, Masrour’s incompetence and arrogance now push the region to its worst political crisis since the 1994-97 civil war. Nor did White House action bolster American credibility. Rather it showed that once again, Washington’s concept of friendship is one-way, and its approach to allies is transitory. Not only Iraqis, but also others across the region, saw U.S. moves as a sign that intransigence beats loyalty.

The United States perennially underappreciates Iraq and consistently fumbles its strategy. First, too many officials continue to view the country only through the lens of Iran rather than on its own terms. Second, Washington prioritizes a series of short-term fixes at the expense of long-term reform and stability. Prioritizing personalities over systems is a formula for failure. It would be hypocritical to say Barham, in such a case, was indispensable. No one should be. But to assess Iraqi candidates in terms of tribal concerns rather than through the lens of who is most capable of advancing a new Iraqi compact is wrong. When Iraqis take to the streets to protest corruption, it is incredible that the Biden administration chooses to side with the most corrupt. Third, and related, the White House and State Departments fail to understand that tolerating corruption breeds more corruption. They should treat Masoud and Masrour as pariahs, not legitimate political actors worthy of American time or support.

Now a 19FortyFive Contributing Editor, Dr. Michael Rubin is a Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI). Dr. Rubin is the author, coauthor, and coeditor of several books exploring diplomacy, Iranian history, Arab culture, Kurdish studies, and Shi’ite politics, including “Seven Pillars: What Really Causes Instability in the Middle East?” (AEI Press, 2019); “Kurdistan Rising” (AEI Press, 2016); “Dancing with the Devil: The Perils of Engaging Rogue Regimes” (Encounter Books, 2014); and “Eternal Iran: Continuity and Chaos” (Palgrave, 2005).