X-20: A Short History – Hypersonic weapons are all the rage these days, but the United States once had a hypersonic space plane that was in development from 1959 to 1962. It was called the X-20 Dyna-Soar (Dynamic Soaring) and was planned to be reusable, with a single pilot and no other crew. The Air Force and Boeing envisioned numerous missions for the X-20, had it been brought to fruition before being canceled in 1963. The X-20 could have been used to conduct reconnaissance, perform scientific research, and even execute hypersonic bombing missions against the Soviet Union.

The X-20 Required Substantial Resources

The Pentagon wanted it to have a concrete military purpose and it was too expensive for use as a technology testbed and research vehicle, so the X-20 did not make it past the prototyping phase. The military and Boeing sunk $410 million (or $3.5 billion in today’s dollars) into the program.

An Early Space Shuttle?

It was an interesting project and ahead of its time. The X-20 paved the way for a reusable spaceplane that could launch on a rocket, conduct its mission, and then glide down to land on an airstrip, just like the space shuttle.

Early Heat Resistant Material for Re-entry and Ground Landing

The Dyna-Soar mockup was 35.5 feet long with swept delta wings spanning 20.4 feet. It had a rounded shape without the pointy angles associated with fighter planes. There was no wheeled landing gear – it instead used retractable struts. The X-20 had heat-resistant superalloys such as molybdenum, graphite, and zirconia along the underside of the craft.

Early Work Loomed Promising

Several astronauts were chosen to fly the Dyna-Soar including a 30-year-old test pilot and aerospace engineer Neil Armstrong. Pilots were going to start flying the X-20 in evaluation mode after it was airdropped from a B-52 bomber. The public was even allowed to see the X-20 in an exhibition in Las Vegas that wowed the crowd. Testing of the rocket booster was also a success.

Bouncing and Skipping Flight

The immediate future looked bright for the Dyna-Soar. The flight parameters were unique as it was supposed to bounce and skip over the air during flight. As Robert F. Dorr described on Defense Media Network, “At every stage of its design and development, Dyna-Soar was capable of being a fully orbital spacecraft, but as the program moved ahead, emphasis stayed on its capabilities as a suborbital, hypersonic spaceplane/glider that could ‘skip’ along the earth’s atmosphere.”

Future Dyna-Soars Would Have Military Uses

The designers were not concerned about the technical hurdles they would have to overcome for successful flight. They even envisioned a planned iteration called the Dyna-Soar III that would be a hypersonic recon bomber. At these speeds, it allowed the spaceplane to result in only a three-minute enemy radar warning compared to a 20-minute warning with an intercontinental ballistic missile. It could be re-targeted or called back from its original mission, unlike an ICBM.

Recon Capabilities Were Robust

The Dyna-Soar III was planned to conduct over-flight recon duties as well. According to space analysis website Astronautix, “It could glide over enemy targets between 45 and 90-km altitude, providing better resolution than orbiting satellites at much higher altitudes. The data would be available for analysis within hours of the overflight, compared to having to wait for days for the recovery of the capsules from spy satellites. The enemy would also have no warning to conceal its activities, unlike a satellite in its predictable orbit.”

A New Secretary of Defense Was Skeptical

Dyna-Soar III appeared to have that “military purpose” that the government was looking for. But the spacecraft plans were optimistic, and a fully flying craft would need hundreds of millions more dollars. The Dyna-Soar III would not be ready until the early 1970s. This was going to require too much money and resources. Designers were not sure what to use for its launch vehicle. The Dyna-Soar program was also a victim of politics and different policymakers in the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations who didn’t agree on what constituted civilian space or military space projects. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara was no fan and funding dried up. McNamara finally called no joy, and the Dyna-Soar program was kaput in 1963.

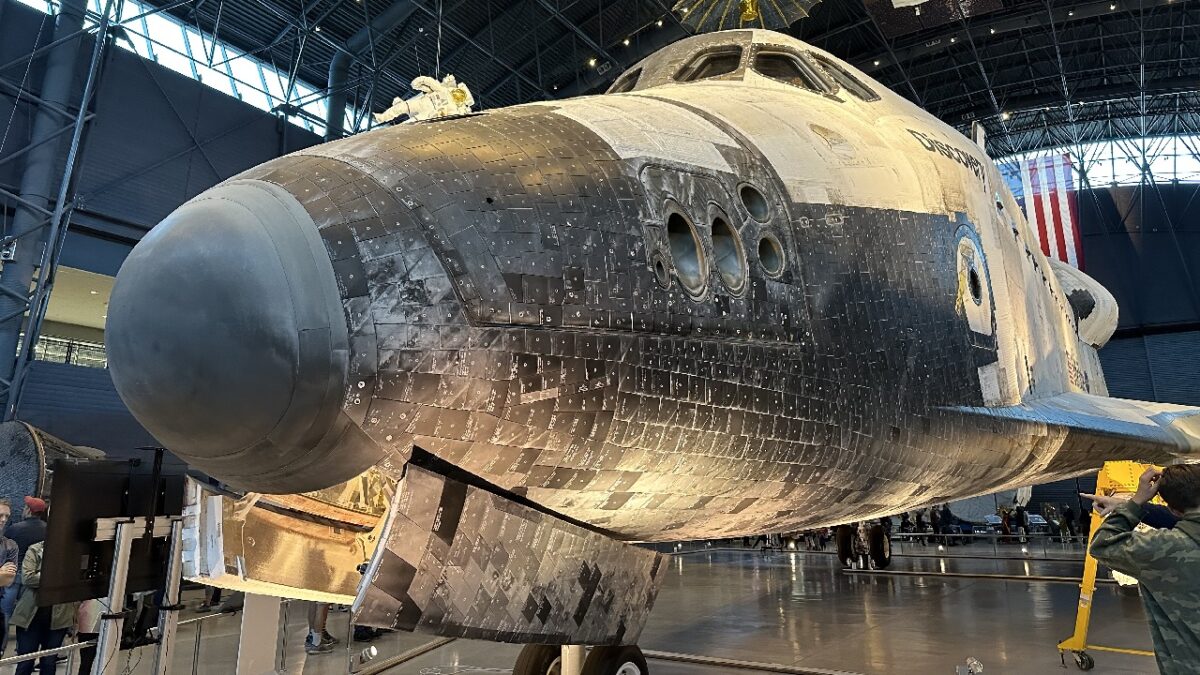

Bonus: Space Shuttle Photo Essay

Shuttle Discovery at National Air and Space Museum on October 1, 2022. Image Credit: 19FortyFive.com

NASA’s Space Shuttle Discovery. Image Taken by 19FortyFive.com on October 1, 2022.

NASA Space Shuttle Discovery. Image Credit: 19FortyFive.com taken on October 1, 2022.

Now serving as 1945’s Defense and National Security Editor, Brent M. Eastwood, Ph.D., is the author of Humans, Machines, and Data: Future Trends in Warfare. He is an Emerging Threats expert and former U.S. Army Infantry officer. You can follow him on Twitter @BMEastwood.