In case you’ve just arrived from Mars, the Australian government has announced it will acquire, with the assistance of the United States and the United Kingdom, a fleet of nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSNs) that will be built in Australia. It has also said that the first submarine won’t be operational until the late 2030s. Since the government pre-emptively canceled the Attack-class submarine program, the Collins class will need to serve as the core of the Royal Australian Navy’s submarine fleet into the 2040s.

The risk associated with operating a small fleet of very old boats, particularly as we are trying to increase to a much larger number of submariners, has already led to calls for a Plan B. One idea that has been raised many times involves the purchase or lease of used American or British SSNs to jump-start the transition to a nuclear fleet. Let’s look at the information that could inform a decision on that kind of option.

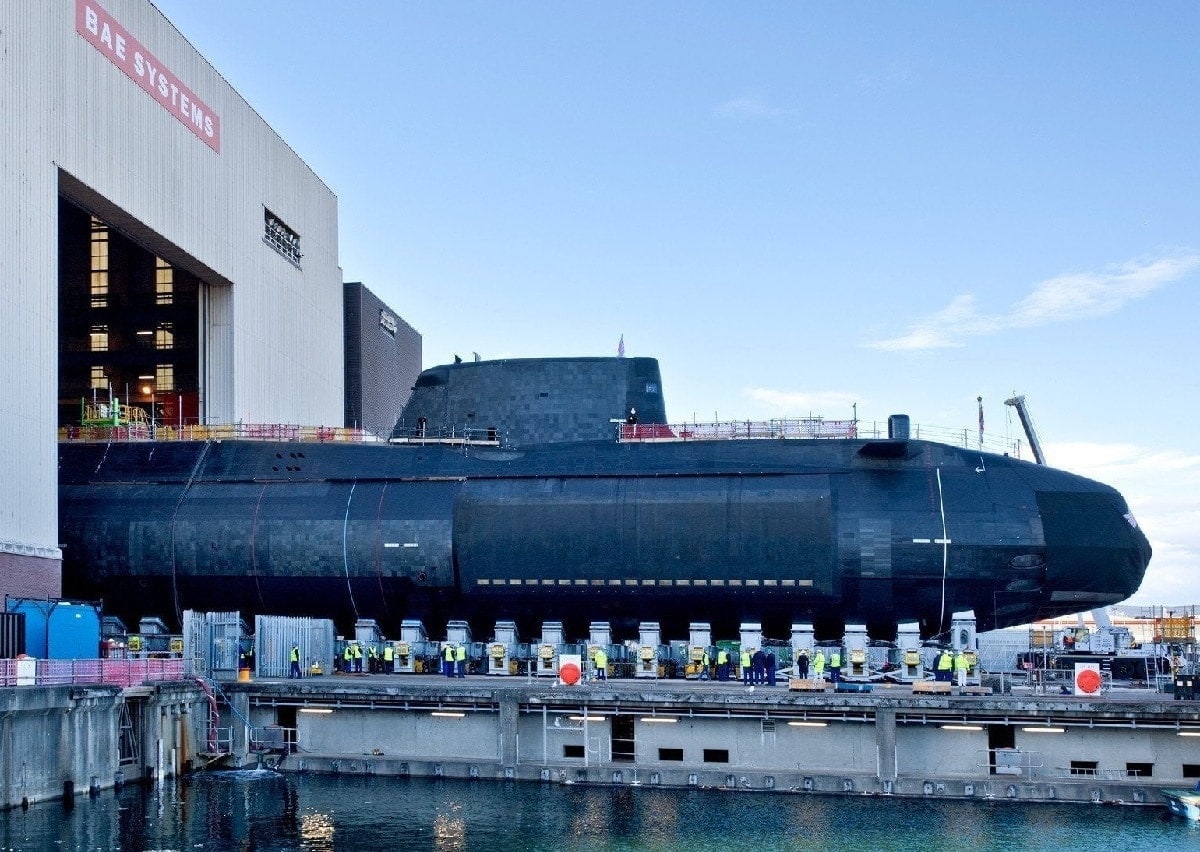

It’s reasonable to assume neither the US nor the UK will provide us with any existing boats from their new classes, the Virginia and Astute, respectively. The Royal Navy is now in the middle of a transition from the seven-boat Trafalgar fleet to the seven-boat Astute fleet. Four Astutes are in service, and the final three are in various stages of construction. The last is (rather optimistically) scheduled to enter service by 2026. Handing over even one Astute would put a huge dent in the RN’s capability.

The US Navy is building two Virginias each year and, so far, has around 20 in service. While the USN’s shipbuilding plans have been in flux, one constant element is that it wants to increase the size of its SSN fleet significantly as it’s one area where it retains a technological advantage over China. However, it’s facing a capability squeeze in the short to medium term as its older fleet of Los Angeles–class boats potentially retire faster than Virginias are built. It certainly isn’t looking to off-load Virginias.

We can’t say for certain that it won’t happen—presidents and prime ministers can make unpredictable decisions, as we’ve seen—but the point of AUKUS is to increase the three partners’ capability. Handing over an extremely scarce resource like an SSN to a country that doesn’t know how to operate it and doesn’t have the human or industrial resources to support it would be a net loss of capability to the partnership.

So that leaves our AUKUS partners’ older classes, the RN’s Trafalgar class, and the USN’s Los Angeles class. The first thing we should emphasize is that safety is absolutely paramount in any submarine program, and even more so in a nuclear one. If a boat is no longer certified by the relevant authorities for safe operation, you can’t simply wish that away, cross your fingers and hope for the best. And since we don’t have the ability to certify it, the original owner will be assuming the liability. So, while an old nuclear boat might look like a good deal to us, it may not be a good deal for the original owner that would need to keep putting resources into an old class of boats it had hoped to move on from.

Let’s start with the UK option. The RN still has the last two of the original seven Trafalgar-class boats in service. Another has recently been laid up pending decommissioning. The average age of the three is 31, but the final two will have to keep going to meet up with the commissioning of the last Astutes, which has stretched out longer than planned. A detailed investigation would be needed to determine how serviceable they will be at that point. The reactor cores may have some life left in them, but it won’t be enough to bridge the gap to new Australian submarines being delivered in the late 2030s, at which point the last Trafalgars will be approaching 50. So they’d probably need to be refueled and refurbished for Australian service.

The Trafalgar class was designed to be refuelled; the last refuel and refit was completed in 2011 and took six years at a cost of nearly £300 million. However, in light of the detailed reports into the risks the UK Ministry of Defence is facing in sustaining its current nuclear capabilities while delivering new ones, it’s not immediately obvious that 10 years down the track it will still have the ability to produce a new reactor core for the Trafalgar’s PWR1 reactor, which isn’t used on its other classes of nuclear submarines, or that its shipyards will have the capacity to do the work. But let’s assume it can be done and the UK refuels and refits the last two or three Trafalgar-class boats as they are replaced by the last Astute. We’re still looking at the late 2020s for delivery of boats that would be close to 40 years old.

Another challenge is that the RN’s industrial base will have transitioned to support the Astute class, so we would be operating a tiny orphan fleet with no industrial base anywhere in the world to support it. We’re talking about not just the nuclear propulsion system but the thousands of other components on any submarine. It took Australia a couple of decades to really get the sustainment system for the Collins class working well, and we were in that for the long haul.

The Canadians went down the path of a small, orphan fleet when they acquired four second-hand conventional submarines from Britain when the RN decided it was only going to operate nuclear boats. Despite years of repairs and upgrades, the fleet didn’t achieve a single sea day in 2019. I know I tend to be a glass-half-empty person, but acquiring a small number of orphan boats sounds like a recipe for disaster.

In my next post, I’ll look at the US option.

Marcus Hellyer is a senior analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. This first appeared in ASPI’s The Strategist.