As Russian troops continue to mass around Ukraine, the United States and many of its NATO allies have begun deploying combat troops, warships, and aircraft to Eastern Europe to reassure anxious member states bordering Ukraine and Belarus.

Washington has dispatched 3,000 airborne and mechanized infantry soldiers and a half-dozen F-15 fighters, while London is deploying more than 1,000 additional troops. An additional 8,500 U.S. troops remain on heightened alert status, meaning they could deploy on short notice, perhaps in event of Russian escalation in Ukraine.

Nonetheless, Washington and NATO leaders have emphasized the new troops would not be sent into Ukraine, neither preemptively nor in event of a Russian invasion. That is manifestly credible because the forces involved are relatively small, lack heavy armored vehicles, are widely dispersed, and dwarfed by the tens of thousands of troops Russia has arrayed in western Russia and Belarus.

Poland and the Baltic states are especially concerned with Moscow’s deployment to Belarus of 30,000 troops mostly from its faraway Eastern military District, along with advanced weapon including Iskander and S-400 missiles, and Su-35S fighters. Though conveniently positioned for an offensive on Kyiv, these forces are also on the borders of Poland, Lithuania and Latvia—countries invaded by Moscow in 1939-1940. Currently, Russian battalions in Brest, Belarus (site of a border fortress Soviet troops captured from Poland in 1939) are just 110 miles east of Warsaw.

Further to the south, Romania and Bulgaria are alarmed by Russia’s large naval buildup on the Black Sea, and the possibility that neighboring Ukraine could become a Russian-occupied warzone. Putin’s recently issued demands that NATO withdraw all international troops from these countries are not well received either.

That said, two NATO members bordering Ukraine have not requested NATO deployments yet: Hungary (which has warmer relations with Moscow) and Slovakia.

This article outlines where additional NATO forces are deploying in response to Russia’s buildup around Ukraine, with additional commentary regarding the capabilities of U.S. forces. It also explains what NATO deployments were already present (rotated under the Enhanced Forward Presence policy) that were not there in response to Moscow’s most recent actions.

Poland

- Elements from a brigade of the 82nd Airborne Division (1,700 troops) landing at Rzeszow, 50 miles west of Poland’s border with Ukraine.

The 82nd is a legendary airborne infantry division based in Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Such light infantry units and their towed artillery can be rapidly airlifted across the globe, but are vulnerable to Russian-style mechanized forces due to lacking armored vehicles for mobility, protection and firepower.

Preexisting forces

Poland already hosts 4,500 U.S. troops (going on 5,500), plus a rotating multinational battalion of around 1,000 troops from Croatia, Romania, U.K. and U.S.

Germany

- XVIII Airborne Corps HQ troops (300 soldiers) at Wiesbaden

The XVIII Corps, also based at Fort Bragg, is the long-standing parent formation for U.S. rapid response divisions, notably the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, and the light infantry of the 10th Mountain Division. The 300 soldiers therefore will provide additional support to the troops from the 82nd, as well as likely prepare the ground in the event Washington decides to send more troops to Europe.

Romania

- Planned: “Hundreds” of additional French troops to deploy to Romania and lead a multinational force.

- Elements of U.S. Army’s 2nd Cavalry Regiment (1,000 troops) moved from Germany to Romania

This 2nd Cavalry has been stationed in Vilseck, Germany since 2006. It disposes of three infantry and one scout squadrons (ie. battalions) all mounted on 18-ton Stryker 8×8 wheeled armored personnel carriers, as well as an engineer and field artillery squadrons and other support units.

Though more affordable to operate and easier to transport, the Stryker was criticized in the past for lacking the firepower to counter Russian mechanized forces. Recently, the Army has sought to address this shortcoming by integrating new turrets on some Strykers with 30-millimeter cannons (Stryker Dragoon) and Javelin missiles (CROWS-J). The 2nd Cavalry happens to have been the lead unit to test the up-gunned Stryker.

Preexisting NATO Deployment

Since 2017, there’s been a 5,000-strong NATO Multinational Brigade Southeast based in Craiova, composed 80% of Romanian troops, but with international elements, especially from Poland and Bulgaria. Italy currently deploys four Eurofighters and 140 personnel for air policing; they are due to be relieved by German Eurofighters.

900 U.S. military personnel are based in Romania, including air cavalry and armored elements at Mikhail Kogalniceau Airbase, and USAF drone operators at Campia Turzii.

Russia-Romania relations have been poisoned by a frozen conflict in neighboring Moldova, formerly part of Romania. In the 1990s, Russia’s 14th Guards Army intervened to prop up a separatist republic on the east bank of the Dniester River called Transnistria. Some analysts Russian forces remaining there could be activated for military action in Ukraine.

Moscow, in turn, professes outrage at the U.S. Aegis Ashore missile defense system deployed in Deveselu in southwestern Romania, claiming its launchers could also fire offensive Tomahawk land-attack missiles.

Bulgaria

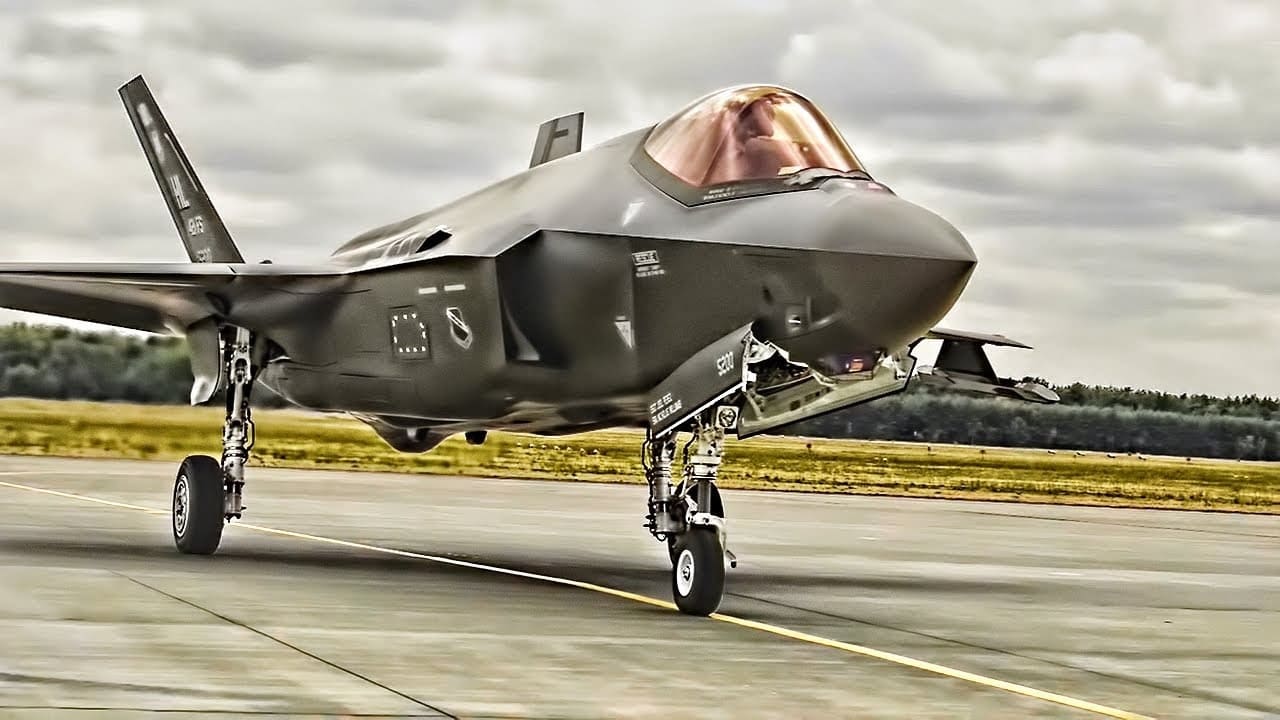

- 2x Dutch F-35A Lightning stealth fighters to perform Quick Reaction Alert interceptions

- 4x Spanish Eurofighter jets supported by 200 personnel

- Planned: 1,000-strong Bulgarian-led multinational battalion to form in April-May

- British RAF Typhoon squadron (based in Cyprus to patrol Black Sea airspace)

Like Romania, Bulgaria is another NATO state with a Black Sea coastline. Russia’s demands that NATO withdraw foreign troops from Romania and Bulgaria haven’t been appreciated.

A U.S. Air Force F-35A Lightning II fighter jet performs during the California International Airshow in Salinas, California, Oct. 30, 2021. The F-35A is a fifth-generation multi-role fighter platform. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Andrew D. Sarver)

Preexisting Forces

Bulgaria is presently hosting 200 U.S. mechanized troops for training through June.

The Baltics: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania

The Baltics have long been vulnerable to encompassing Russian forces in Kaliningrad, Belarus, and western Russia, so Moscow’s current military flex is raising alarm. NATO contingents rotated there would only serve as a speed bump or trip-wire against a serious Russian attack, serving to buy time and boost political will until more substantial forces could enter the theater.

U.S. Military

- 6x F-15E Strike Eagle fighter-bombers of the North Carolina-based 336th Fighter Squadron deployed to Ämari Airbase in Estonia (with 120 personnel)

Fast and heavy-lifting, the two-seat F-15Es are capable ground-attack aircraft that can still carry their weight in an air superiority role. However, they are not stealth aircraft, so the Air Force would avoid dispatching these too deeply into airspace interdicted by Russia’s extensive air defense systems.

An F-15E flies watch over the skies of Afghanistan on July 30. The F-15 and crew are deployed to Bagram Air Field, Afghanistan, from Mountain Home Air Force Base, Idaho.

British military

- Paratroopers (presumably from 16th Air Assault Brigade)

- 45 Commando Battalion of the Royal Marines

- Royal Signals Troops and Y Squadron, Royal Marines (Electronic and Cyber Warfare specialists)

- 26th Regiment Royal Artillery (M270 Multiple-Rock Launchers systems) to Estonia

- 47th Regiment Royal Artillery (equipped with WK450 Watchkeeper recon/targeting drones)

- 6x AH1 Apache attack helicopters

- 6x Chinook heavy transport helicopters (RAF)

London is reportedly planning dispatch of up to 1,200 British Army, Royal Marine, and Royal Air Force personnel to unspecified destinations in the Baltics.

Danish Military

- 4x F-16 fighters to Lithuania

- 1x Iver-Huitfeldt-class air defense frigate Peter Willemoes to Baltic

Pre-existing Deployments

Estonia hosts a rotating multinational mechanized battlegroup of 900 personnel, currently including troops from Denmark, France, Iceland and the United Kingdom. Four Belgian F-16 jets are based there on air-policing duties.

Lithuania hosts a multinational mechanized battalion with 1,200 personnel, including troops from Belgium, the Czech Republic, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway; and a U.S. mechanized infantry battalion with 500 soldiers. Four Polish F-16 jets are based there for Baltic air policing.

Latvia also has a Canadian-led multinational battlegroup with 1,500 personnel.

The Black Sea

- 1x French frigate

- Canadian Halifix-class multi-role frigate Montréal

British Royal Navy

- River-class Offshore Patrol Vessel dispatched to Black Sea (likely HMS Trent)

- Type 45 air defense destroyer (likely HMS Diamond)

Spanish Navy

- Álvaro de Bazán-class Aegis air defense frigate Blas de Lezo

- Segura-class minehunter Sella

Russia is heavily reinforcing its formidable Black Sea Fleet with warships and amphibious landing craft from Russia’s Northern, Baltic and Pacific currently in transit via the Mediterranean. Despite Russia’s extensive maritime strike capabilities in the Black Sea’s confines, Spain, France and the United Kingdom have dispatched ships to patrol its international waters and surveil Russian military activity.

Far more powerful NATO forces cruise in the neighboring Mediterranean, including Italian, French, British and U.S. carrier strike groups, counting dozens of F-35B stealth jump jets, and Rafale-M and Super Hornet fighters.

NATO Advisors in Ukraine

- 150x U.S. Special Forces and Florida National Guard personnel

- 100x British Army personnel as part of Operational Orbital

- 200x going on 260 Canadian Special Forces personnel

- Small numbers of advisors from around 10 other countries

Since 2014, several hundred NATO military advisors have been deployed to Ukraine to train and advise its military. U.S. and British troops are also instructing Ukrainian troops on use of recently transferred NLAW, Javelin and Stinger missiles.

These advisors are not equipped for serious combat, and would surely be instructed to avoid combat with Russian forces should they invade. However, they do enhance the proficiency of Ukraine’s armed forces, and should Russia attack Ukraine, some possibly might remain in country to advise and liaise with Ukraine’s military.

Summary

Moscow predictably has decried the deployments as “destructive” stepping stones to World War III. But NATO’s recent deployments are meant for signaling, not to fight a Russian invasion of Ukraine. That’s not an assertion reliant on trusting Washington press releases, just observing material reality.

NATO’s latest deployments lack the mass and heavy weapons to counter the hundreds of armored vehicles and heavy artillery and missile systems Russia has concentrated in the region. Even the heavier elements of NATO’s preexisting Enhanced Forward Presence amount to roughly a half-dozen mechanized battalions, compared to the 70 to 100 Russian battalion tactical groups arrayed in Belarus and western Russia.

The deployments simply assure NATO’s eastern members the alliance will put its troops on the line to protect them, particularly as Putin contemplates pulling the trigger on what could become the most destructive armed conflict in Europe since World War II.

Sébastien Roblin writes on the technical, historical, and political aspects of international security and conflict for publications including the 19FortyFive, The National Interest, NBC News, Forbes.com, and War is Boring. He holds a Master’s degree from Georgetown University and served with the Peace Corps in China. You can follow his articles on Twitter.